Team:Bielefeld-Germany/Project/Theory

From 2010.igem.org

Contents |

Introduction

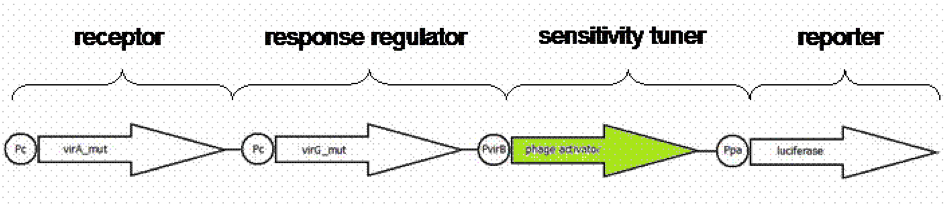

In our iGEM project we created an E. coli cell which is capable to sense capsaicin in a complex sample and report the concentration with a luciferase light signal. We combined a native receptor system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens with the readout system of the firefly luciferase. The native receptor senses the phenolic compound acetosyringone. For this reason we used directed evolution to modify the binding region of the native receptor to generate a new capsaicin receptor, because of the chemical similarities of acetosyringon and capsaicin. We established a screening system based on antibiotic concentration gradients to screen the newly generated receptors. In our E. coli acetosyringone sensing system several parts derived from different organisms were assembled; The readout system taken from firefly luciferase, the receptor sensing system derived from Agrobacterium tumefaciens and sensitivity tuners consist of phage dna.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens

The model organism Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a soil bacterium and can be found at nearly every point of the world. Agrobacterium became known as a phyto-pathogen leading to the crown gall disease in dicotyledonous species ([http://www.springerlink.com/content/hm17520m287ht766/ DeCleene M and DeLay J, 1976]). The infection is caused by a gene transfer system located on an extrachromosomal element, the Ti-plasmid. Furthermore the infection can be divided into several steps. The first step is the localisation of the hurt plant by the bacteria. Predominantely A. tumefaciens senses phenolic compunds from hurted plants, but also aldose monosaccharides, low pH and low phosphate ([http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.052002.095701?journalCode=phyto Palmer AG. et al.2004]; [http://mmbr.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/69/1/155 Brencic A and Winans SC, 2005]). When A. tumefaciens recognizes phenols with the virA receptor, a signal transduction cascade is initiated leadig to the expression of virulence genes. The next step is a physical interaction with the host plant. A type three secretion system is responsible for the DNA transfer of the Ti-plasmid from the bacterium into the host. The DNA is translocated to the nucleus, leading to the gene expression and the production of opin. A. tumefaciens uses the reprogrammed plant cells for metabolite production and therefore as a nutrient supplier.

For biotechnology purpose the Ti-plasmid was disharmed. Instead the native transfer region (T-region) and a gene of interest could be easily introduced into the Ti-plasmid. Agrobacterium-mediated DNA transfer is one of the most commonly used techniques of plant transformation ([http://people.uleth.ca/~alicja.ziemienowicz/extra/Ziemienowicz_ABP2001.pdf Ziemienowicz A, 2001]).

Native receptor

A. tumefaciens needs a precise recognition system for potential hosts, to gain an evolutionary advance. The native sensing system is a two-component phospho-relay system in which VirA is an transmembrane-bound sensor while VirG is the intracellular response regulator ([http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/gb-2002-3-10-reviews3013.pdf Wolanin PM et al., 2002]). The two genes for the sensing system are virA and virG ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1166964/ Stachel SE and Nester EW, 1986]) which are constitutively expressed at a basal level. VirA is a histidine kinase. An autophosphorylation occurs at the His-474 residue, after sensing the phenol 3,5-Dimethoxyacetophenone, Acetosyringone ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC208549/?pageindex=1&tool=pmcentrez Huang Y et al., 1990] ; [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/172/2/531 Jin SG et al., 1990a]). In the next step in the signal transduction cascade, the phosphorylated VirA leads to the transfer of the phosphate to Asp-52 residue of VirG ([http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/172/2/531 Jin SG et al., 1990a] ; [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/172/9/4945 Jin SG et al., 1990b] ; [http://nar.oxfordjournals.org/content/18/23/6909.short Pazour GJ and Das A, 1990]). VirG is the response regulator of the two-component system [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1082791/ (Brencic A, Winans SC, 2005)] and acts as a transcription factor. Hence it binds to the virulence box (vir Box) containing promotors, for example virB ([http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/172/2/531 Jin SG et al., 1990a] ; [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/172/3/1241 Pazour GJ and Das A, 1990]).

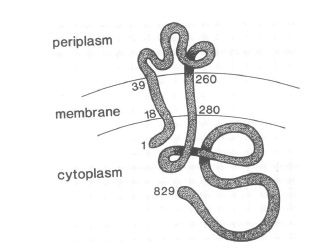

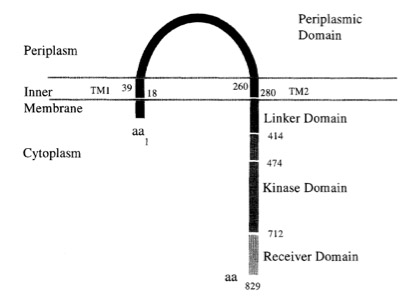

VirA receptor structure

The virA receptor consists of 829 amino acids and is a transmembrane protein in the inner menbrane of A. tumefaciens ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC401051/ Melchers LS, 1989]). VirA spans the inner membrane, with two transmembrane domains, a large periplasmic region, and a large C-terminal cytoplasmic domain ([http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/176/11/3242 Banta LM, 1994]). VirA directly senses the phenolic compounds for vir activation ([http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378111996003289 Lee YW et al., 1996]). Therefore the linker domain is essential for induction by phenolic compounds ([http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/174/21/7033 Chang CH and Winans SC., 1992]). The linker region is located in the cytosolic site at position 280 to 414 ([http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378111996003289 Lee YW et al., 1996]). This region between the amino acids 283 and 304 was highly conserved in four different strains of Agrobacterium, and therefore likely to serve as the receptor region for the phenolic inducers which are common to all four strains ([http://www.springerlink.com/index/G548R7745685341P.pdf Turk SC et al., 1994]).

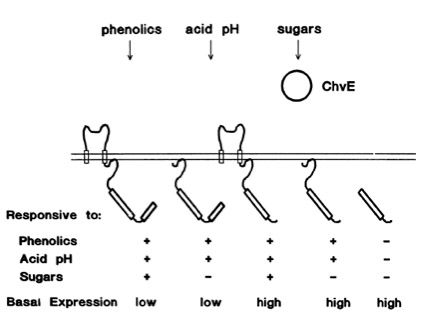

Chang and Winnans (1992) revealed in their studies, the parts of the VirA receptor essential for the signal transduction ([http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/174/21/7033 Chang CH and Winans SC., 1992]). A structured model for different inducing conditions are shown in the figure below.

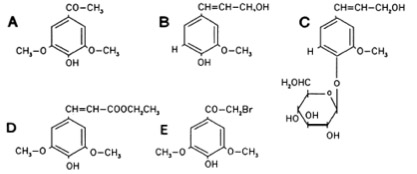

Phenolic Compounds

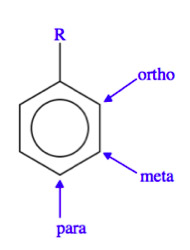

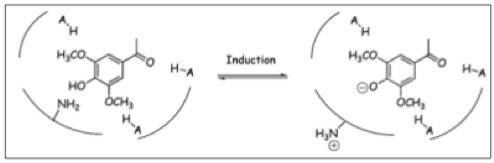

The Ligand receptor interaction between acetosyringone and VirA is based on the interaction of several chemical groups. First of all the hydroxylated aromat is essential. Metoxy groups in the ortho position of the phenol play a crucial role in the signaling as well. It should be mentioned that dimetoxy compounds have a higher activity than monometoxy compounds. The acetyl and alkyl groups in para position enhancing the binding affinity. VirA activating compounds must have two metoxy groups in the ortho position and an additional carbonyl group on the R3 chain. The potential capacity of the group para to the phenolic hydroxyl group is associated with higher activities. Moreover the chirality at this carbon center is critical for the inducing activity ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC372852/?pageindex=1&tool=pmcentrez Winans SC, 1992]). Regarding to the proton transfer model of Hess et al. (1996) the VirA activator transfers a proton to the basic area receptor binding site. The allosteric change leads to the phosphotransfer and the signaltransduction ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC52402/?pageindex=1&tool=pmcentrez Hess KM et al., 1991]).

Inducing enhancers

The sensitivity of this system is highly enhanced when additional aldose monosacchardic suggars occur in the environment of Agrobacterium. The sugar binding protein ChvE interact with the VirA receptor, leading to a much stronger vir gene expression ([http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/176/11/3242 Banta LM, et al., 1994]).

Subcloning into E. coli and receptor function in new host

In our project we decided to work with E. coli instead of A. tumefaciens. The transcription procedure in E. coli is very similar to A. tumefaciens but not complete homolog. In E. coli the rpoA gene - encoding the α-subunit of RNA polymerase in A. tumefaciens - is not present but essential for the transcription of a virB promoter-driven genes ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC103583/?report=abstract&tool=pmcentrez Lohrke SM et al., 1990]) For this reason it was necessary to subclone a modified virG gene that is capable to be trancribed by the E. coli expression system.

Yong-Chul et al. (2004) described VirG mutants that are capable of expressing the virB promoter-driven genes in E. coli without the requirement for the RpoA from A. tumefaciens, suggesting that the virG mutants are able to interact with the transcription system of E. coli ([http://www.springerlink.com/content/wmq06kua5qkma1au/fulltext.pdf Yong-Chul J et al., 2004]). In VirG the amino acid at position 56 is likely to play a key role in the interaction with the RpoA of E. coli. Regarding to Yong-Chul J et al. (2004) we used virG mutants, with amino acid substitutions of G56V and I77V that are capable of activating vir genes in E. coli in response to inducer acetosyringone in a virA-dependent manner.

Read out system

Firefly Luciferase

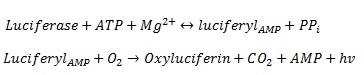

We are using luciferase as the read out system. The luciferase was extracted from the firefly Photinus pyralis. It is one of the best studied and characterized read out systems. The luciferase enzyme catalyses the chemical reaction from its substrate luceferin to oxyluceferin and light ([http://mcb.asm.org/cgi/reprint/7/2/725 De Wet et al. 1986]). The figure 8 shows the reaction in detail.

We used luciferase as the read out system because it causes only slight negligible noise, hence the signal to noise ration is excellent.

Output-signal amplification by Sensitivity Tuner implementation

Using a standard, inducible promoter/reporter system often results in weak reporter expression and so in difficulties in quantification. The quantification can be enhanced by an amplification of the transcription rate of the desired genes. Such an amplification can be realized using so called sensitivity tuner devices. This takes place as promoter induction upregulates a phage activator, which binds to a phage promoter upstream of a reporter. As result a PoPs input (Inducer) generate a PoPs output at a higher signal. PoPs is equivalent to the flow of RNA polymerase molecules along DNA ([http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/abstract/178/19/5668 Julien and Calendar, 1996] ; [http://parts.mit.edu/igem07/index.php/Cambridge/Amplifier_project iGEM Team Cambridge, 2009]).

Purpose of Sensitivity Tuner application

We presumed weak expression rates of our reporter luciferase indicated by pretesting the native system [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K389015 K389015]. For having a broader range of quantification for our prototype test system, an amplification device was implemented. For amplifying the output signal of luciferase induced by acetosyringone, three sensitivity tuner distinguished by the amplification factor were combined with our detection system. To modify the sensitivity tuner for our purpose we took BioBricks with amplification factors from 15 ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I746370 I746370]), 10 ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I746370 I746380]) and 35 ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I746370 I746390]) removed pBAD/araC promotor ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I0500 I0500]) and GFP ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E0040 E0040]) by self- designed primer PCR and replaced it upstream by a VirA/G response regulater [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K389015 K389015] and Virb promoter element [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K389003 K389003] and downstream by the reporter [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K389004 K389004], a luciferase (Figure 9). The benefits of luciferase reporter instead of GFP are a broader range of measurement, higher sensitivity and low half-live making cinetic tests possible ([http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6W9V-4F031H9-30&_user=10&_coverDate=01%2F31%2F1989&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_origin=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1514624813&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=ee400628b119490fcdc44ccdd856c4e8&searchtype=a Williams et al.1989]).

For test results click Sensitivity Tuner amplified Vir-test system

Receptor modification strategy

The smartest way of receptor-modification is initiated by a silico approach, based on a 3D structure of the native receptor. Followed by primer mutagenesis of the computantional gained results a precise adapted peptide emerges. This concept has been proofen by ([http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v423/n6936/abs/nature01556.html Looger et al., 2003]).

Because of time limitations within the iGEM competition and a leck of biological data in literature - no x-ray cristalography structure data for VirA linker region available- this strategy was not applicable. Therefore we developed two different stragies in our MARSS project:

The first strategy was an error prone PCR approach by building a mutant data base for selection. The second strategy was a primer mutagenesis based approach.

Random mutagenesis by error-prone PCR (EP-PCR)

In order to detect novel substances (e.g. capsaicin) with the virA receptor, the first step was to create a mutagenised library of virA variants, which could subsequently be screened for new binding characteristics. Plenty of different strategies for mutagenesis of DNA are known, including the use nucleotide analogues, bacteria containing mutator genes, the mutagenesis with UV light or chemicals and inaccurate PCR ([http://genome.cshlp.org/content/2/1/28.short Cadwell RC and Joyce GF, 1992]).

When designing our strategy we rejected the use of bacteria strains with high mutation rates, since the changes in base sequence would occur all over the transformed plasmids. Thereby some mutations would also take place in the backbone of the plasmid, our might even been found in the standardized BioBrick prefix and suffix. We also excluded the possibility of using UV light or mutagenic chemicals, due to reasons of safety and minimizing the exposure of toxic substances.

In our experiment we wanted to alter only the part of the plasmid coding for the virA receptor, while using a not harmful and thereby safe technique. Thus, our method of choice was inaccurate PCR that allows the exclusive variations of a distinct region of a plasmid, which is defined by the location of the upstream and downstream primers. This mutagenic method of PCR, called error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) has been described and improved a lot in scientific community ([http://www.springerlink.com/content/r62q360t82764508/#section=746282&page=1 McCullum EO et al., 2010]).

The basic principle of this technique uses the natural high infidelity of the Taq DNA polymerase, which can even be increased by special changes in buffer conditions compared to standard PCR. These alterations may include the unequal distribution of dNTPs (5 mM purines, 25 mM pyrimidines) as well as an increased amount of MgCl2 and the addition of MnCl2. The total rate of base exchange can be adjusted by the number of PCR cycles, since mutations will accumulate during the exponential amplification of the sequence ([http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/0471142727.mb0803s51/full Wilson DS and Keefe AD, 2000]). The experimental conditions of the performed error-prone PCR are described in the section “protocols”.

Directed mutagenesis

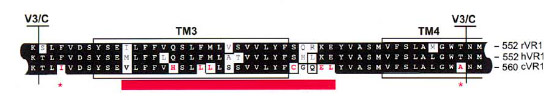

After the identification of the 100 amino acids linker region responsible of VirA ligand binding (Compare VirA-Receptor) we compared this region with well characterized capsaicin receptors derived from animal model organisms (TRPV1). The conserved receptor region is shown in the figure beneath.

The species-specific sensitivity of TRPV1 can be ascribed to about eight amino acids in the vicinity of TM3 ([http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WSN-4C5H6M5-F&_user=2459438&_coverDate=02%2F08%2F2002&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_origin=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000057302&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=2459438&md5=93a9e63f48d785a0b400131a058ee269&searchtype=a Jordt an Julius 2002]).

We further aligned the TM3 region of the TRPV1 receptor to the ligand binding region of the native VirA receptor from Agrobacterium by the use of the tool MUltiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation ([http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/muscle/index.html Muscle]).

For detailed approach of directed mutagenesis for VirA_mut1 and VirA_mut2 click here

Screening system

Development of a high-troughput screening

The screening of randomly mutagenised genes for a desired function or application is always a very time-consuming procedure ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1496376 Beaudry and Joyce, 1992]). It requires a huge amount of material and might takes several months or even years to result in a promising new version of a gene ([http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/17/7/1050.long Hanczyc and Dorit, 2000]). As we faced the challenge to modify the virA receptor in only few weeks we designed a strategy for a fast high-throughput screening, by using subsequent steps of different read out systems and a strategy with two different plasmids.

In the first step after mutagenesis of virA it is necessary to separate thousands of transformants with minor or unwanted changes in the virA gene, from few bacteria that included interesting virA variants. Thus, we wanted to construct our system to lead in the expression of a kanamycin resistance after the induction of the virA receptor, enabling the quick exclusion of all unwanted virA variants.

For that purpose a kanamycin resistance cassette should be set under control of the virB promotor, leading in the expression of aminoglycoside phosphotransferase (APH) that can inactivate kanamycin. The mode of inactivation is the transfer of the y-phosphate from ATP to the hydroxyl group at C3 of the antibiotic ([http://www.bioscience.org/1999/v4/d/wright/wright.pdf Wright and Thompson, 1999]). This phosphorylation results in the loss of binding capacity of the aminoglycoside to the 30S subunit of bacterial ribosomes, which would lead to inhibition of protein synthesis without the presence of the APH ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1365070/pdf/brjclinpharm00008-0014.pdf Begg EJ and Barclay ML, 1995]).

As indicated by the first results, the reporter genes under control of the virB promoter showed a slight but measureable expression without any induction of virA with acetosyringone. This basal transcription resulted in the growth of bacteria without induction of virA at normal working concentrations of kanamycin of 25 to 50 µg mL-1 ([http://books.google.de/books?hl=de&lr=&id=9mO2Fx0CuEYC&oi=fnd&pg=PA4&dq=Molecular+Cloning:+A+Laboratory+Manual,+Vol+1.+&ots=Ctw-SlcSLm&sig=FvweaKb_qiUxClNNiRfdwpmbqdo#v=onepage&q&f=false Sambrook J and Russell DW, 2001]).

Concludingly, prior to the screening experiments it was necessary to adjust the concentration of kanamycin, which inhibits the growth of uninduced bacteria, while allowing bacteria to grow when an appropriate inductor was present and able to activate virA. This analysis was performed using the method of determination of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) as described below.

Determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of kanamycin

There are several ways to investigate the susceptibility of bacteria to inhibiting drugs like antibiotics. Nevertheless, the result of all this tests is the amount of an assayed substance that inhibits visible growth of the bacteria, called the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). The most common way of determination is to grow bacteria in liquids with several concentrations of the inhibiting drug. This procedure is chosen mostly, since many different conditions can be measured at the same time by using microtiterplates ([http://www.nature.com/nprot/journal/v3/n2/abs/nprot.2007.521.html Wiegand I et al., 2008]).

As we planned not to use the kanamycin in liquid culture but in LB-Agar, we chose to determine the MIC at the same conditions as the desired experiment. Therefore, we planned to construct E. coli inhabiting the native virA system and a KanR read out and plated a small volume in different dilutions on LB-Agar without kanamycin. The grown colonies could then be transferred to agar plates with rising concentrations of kanamycin using replica plating. By counting the colonies it should be possible to calculate the percentage of colonies that could withstand each kanamycin concentration. This experiment should be carried out with and without acetosyringone to determine a kanamycin concentration induced E. coli could withstand, while the same population of bacteria dies without the presence of acetosyringone.

Primary selection of virA variants with novel binding properties

After the determination of the MIC the screening for virA variants with new binding properties could be started. The aim of this screening is to find versions of virA that can be induced by one of the tested substances capsaicin, homovanillic acid, dopamine and 3-O methyldopamine.

For that purpose one should transform the mutagenised variants of virA to E. coli and plate the bacteria on LB-agar with the determined kanamycin concentration. At the same time a mixture of all mentioned substances should be present in the agar. All bacteria including a virA variant that is activated by at least one of the substances will grow on the selective agar, since it expresses the kanamycin resistance. With this step it is thereby possible to select thousands of bacteria with unwanted versions of virA from few individuals with wanted binding properties.

At this point it must be mentioned that some grown colonies might still be non-induced and false positive results. As the virA gene has been randomly changed before, it is possible that some variants occur where the receptor is always active. This would lead to a constitutive expression of the reporter gene and thereby a high level of kanamycin resistance. To exclude those false positive clones, the bacteria should be tested whether they are only resistance to the MIC of kanamycin when one of the tested substances is present. Every colony that can withstand the high kanamycin concentration without any inductor includes a constitutive version of virA and should be discarded in futher analysis.

Quantitative analysis of virA variants after induction with novel substances

Should we find some bacteria that respond to the presence of the tested substances (capsaicin, homovanillic acid, dopamine and 3-O methyldopamine) by growing on the MIC of kanamycin, it is desirable to quantify the induction. For that purpose it it is appropriate to change the read out system from kanamycin resistence to luciferase expression. This complex and time consuming task can easily be achieved without any cloning step, when using the advantage of our two plasmid system.

After primary selection each bacteria includes two plasmids with different origins of replication (oris). The plasmid with the virA is in a common psB1AT3 backbone with a ColE1 ori. Contrary to that the read out plasmid with KanR has a special ori, named R6K, which can only amplify in E. coli strains that express the gene pir to produce the so called Pi protein. Most of the strains used in laboratory are pir- but few (e.g EC100D) are pri+ ([http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17383678 Bowers et al., 2007]).

The setup of the different oris was chosen to separate both plamids at this experimental stage. To change the read out system from KanR to luciferase, one just needs to perform two transformations and isolations of plasmids. In the first step plasmids are isolated from colonies with positive binding properties to one of the tested substances. This mixture of plasmids with ColE1 and R6K oris is then transformed to a pir- strain (e.g. TOP10). In the following only the plasmid with ColE1 ori will be amplified during the growth of the transformants, leading to pure plasmids with virA when plasmids are isolated for a second time. In the last step this isolated DNA can be transformed to bacteria including another read out plasmid (e.g. with luciferase).

References

- Banta LM, Joerger RD, Howitz VR, Campbell AM, Binns AN., 1994, Glu-255 outside the predicted ChvE binding site in VirA is crucial for sugar enhancement of acetosyringone perception by Agrobacterium tumefaciens., J Bacteriol. 176(11):3242-9.

- Beaudry AA, Joyce GF (1992) Directed evolution of an RNA enzyme, Science, 257(5070):635-41.

- Begg EJ, Barclay ML (1995) Aminoglycosides – 50 years on, Br J clin Pharmac, 39, 597-603.

- Bowers LM, Krüger R, Filutowicz M (2007) Mechanism of origin activation by monomers of R6K-encoded pi protein, J Mol Biol, 368(4), 928-938.

- Brencic A, Winans SC, 2005, Detection of and response to signals involved in host-microbe interactions by plant-associated bacteria, Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 69: 155–194.

- Cadwell RC and Joyce GF (1992) Randomization of genes by PCR mutagenesis, Genome Res., 28-33.

- Chang CH, Winans SC., 1992, Functional roles assigned to the periplasmic, linker, and receiver domains of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirA protein., J Bacteriol. 174(21):7033-9.

- DeCleene M, DeLay J, 1976, The host range of crown gall, Bot Rev 42: 389–466

- De Wet JR, Wood KV, De Luca M, Helinski DR and Subramani S (1987), Firefly Luciferase Gene: Structure and Expression in Mammalian Cells, Molecular and Cell Biolog, Feb 1987 pp.725-737

- Hanczyz MM, Dortit RL (2000) Replicability and Recurrence in the Experimental Evolution of a Group I Ribozyme, Mol Biol Evol, 17 (7), 1050-1060.

- Hess KM, Dudley MW, Lynn DG, Joerger RD, Binns AN., 1991, Mechanism of phenolic activation of Agrobacterium virulence genes: development of a specific inhibitor of bacterial sensor/response systems., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:7854–58.

- Huang Y, Morel P, Powell B, Cado CI, 1990, VirA, a corregulator of Ti-specific virulence genes, is phosphorylated in vitro., J Bacteriol 172:1142–1144.

- Jin S, Roitsch T, Ankenbauer RG, Gordon MP, Nester EW, 1990, The VirA protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens is autophosphorylated and is essential for vir gene regulation., J Bacteriol 172: 525–530.

- Jin SG, Prusti RK, Roitsch T, Ankenbauer RG, Nester EW, 1990a, Phosphorylation of the VirG protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens by the autophosphorylated VirA protein: Essential role in biological activity of VirG., J Bacteriol 172:4945–4950.

- Jin SG, Roitsch T, Christie PJ, Nester EW, 1990b, The regulatory VirG protein specifically binds to a cis-acting regulatory sequence involved in transcriptional activation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence genes., J Bacteriol 172:531–537

- Jordt SE, Julius D (2002) Molecular Basis for Species-Specific Sensitivity to „Hot“ Chili Peppers, Cell, Vol. 108, 421-430.

- Kyunghee Lee, 1996, A structure-based activation model of phenol-receptor protein interactions.

- Lee YW, Jin S, Sim WS, Nester EW, 1996, The sensing of plant signal molecules by Agrobacterium: genetic evidence for direct recognition of phenolic inducers by the VirA protein., Gene. 179(1):83-8.

- Lin, Y, Gao R, Binns A, Lynn D, (2008), Bacterial signal transduction: networks and drug targets Adv Exp Med Biol. 161–177.

- Lohrke SM, Nechaev S, Yang H, Severinov K, Jin SJ, 1999, Transcriptional activation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence gene promoters in Escherichia coli requires the A. tumefaciens RpoA gene, encoding the alpha subunit of RNA polymerase., J Bacteriol 181:4533–4539.

- Looger et al., (2003), Computational design of receptor and sensor proteins with novel functions, Nature 423, 185-190.

- McCullen CA., Binns AN. , 2006, Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Plant Cell Interactions and Activities Required for Interkingdom Macromolecular Transfer, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22:101-127

- McCullum EO, Willliams BAR, Zhang J, Chaput JC (2010) Random Mutagenesis by Error-Prone PCR, In vitro mutagenesis protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol 634, 103-109.

- Melchers LS, 1989, Membrane topology and functional analysis of the sensory protein VirA of Agrobacterium tumefaciens., The EMBO Journal vol.8 no.7 pp.1919- 1925.

- MUltiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation. MUSCLE http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/muscle/index.html

- Palmer AG, Gao R, Maresh J, Erbil WK, Lynn DG, 2004 Chemical biology of multi-host/pathogen interactions: chemical perception and metabolic complementation, Annu Rev Phytopathol 42: 439–464.

- Pazour GJ, Das A, 1990, Characterization of the VirG binding site of Agrobacterium tumefaciens., Nucleic Acids Res 18:6909–6913.

- Pazour GJ, Das A, 1990, virG, an Agrobacterium tumefaciens transcriptional activator, initiates translation at a UUG codon and is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein., J Bacteriol 172:1241– 1249.

- Sambrook J, Russel DW (2001) Molecular Cloning – A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Vol 1.

- Scott M., Lohrke, 2001, Reconstitution of Acetosyringone-Mediated Agrobacterium tumefaciens Virulence Gene Expression in the Heterologous Host Escherichia coli ., J. of Bacteriology, p. 3704–3711 Vol. 183, No. 12.

- Shimoda N,Toyoda-Yamamoto A, Shinsuke S, Machica Y., 1993, Genetic evidence for an interaction between the VirA sensor protein and the ChvE sugar-binding protein of Agrobacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 268:26552–58

- Stachel SE, Nester EW, 1986, The genetic and transcriptional organization of the vir region of the A6 Ti plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens., EMBO J 5: 1445–1454.

- Turk SC, van Lange RP, Regensburg-Tuïnk TJ, Hooykaas PJ., 1994, Localization of the VirA domain involved in acetosyringone-mediated vir gene induction in Agrobacterium tumefaciens., Plant Mol Biol. 25(5):899-907.

- Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancok REW (2008) Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances, Nature Protocols, 3 , 163-175.

- Williams TM, Burlein JE, Ogden S, Kricka LJ and Kant JA, 1989 Advantages of firefly luciferase as a reporter gene: Application to the interleukin-2 gene promoter, Analytical Biochemistry, Vol. 176, pp. 28-32

- Winans SC., 1992, Two-way chemical signaling in Agrobacterium-plant interactions., Microbiol Rev. 56(1):12-31.

- Wilson DS, Keefe AD (2000) Random Mutagenesis by PCR, Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, 8.3.1-8.3.9.

- Wolanin PM, Thomason PA, Stock J.B., 2002, Histidine protein kinases: key signal transducers outside the animal kingdom., Genome Biol 3: REVIEWS3013.

- Wright GD, Thompson PR (1999) Aminoglycoside phosphotransferases: Proteins, Structure and Mechanism, Frontiers in Bioscience 4, d9-21.

- Yi Han Linn et al., 2008, Capturing the VirA/VirG TCS of Agrobacterium tumefaciens., Adv Exp Med Biol. 631:161-77.

- Yi-Han Lin et al., 2007, The initial steps in Agrobacterium tumefaciens pathogenesis: chemical biology of host recognition, Agrobacterium: From Biology to Biotechnology,2008, pp. 221-241.

- Yong-Chul J., Yunrong G., Donghai W., Shouguang J., 2004, Mutants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens virG Gene That Activate Transcription of vir Promoter in Escherichia coli, Current Microbiology Vol. 49, pp. 334–340.

- Ziemienowicz A., 2001, Odyssey of agrobacterium T-DNA,. Acta Biochim Pol. 2001;48(3):623-35.

"

"