Team:Imperial College London/Modelling/Protein Display/Detailed Description

From 2010.igem.org

| Modelling | Overview | Detection Model | Signaling Model | Fast Response Model | Interactions |

| A major part of the project consisted of modelling each module. This enabled us to decide which ideas we should implement. Look at the Fast Response page for a great example of how modelling has made a major impact on our design! | |

| Objectives | Description | Results | Constants | MATLAB Code |

| Detailed Description |

This model consists of eight parts that had to be developed:

|

| 1. Elements of the system |

|

| 2. Interactions between elements |

|

Apart from the proteins being expressed from genes, there was only one more chemical reaction identified in this part of the system. This is the cleavage of proteins, which is an enzymatic reaction:

This enzymatic reaction can be rewritten as a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), which is of similar form to the 1-step amplification model.  |

| 3. Threshold concentration of AIP |

|

The optimal peptide concentration required to activate ComD is 10 ng/ml [1]. This is the threshold value for ComD activation. However, the minimum concentration of peptide to give a detectable activation is 0.5ng/ml.

Converting 10 ng/ml to 4.4658×10-9 mol/L

|

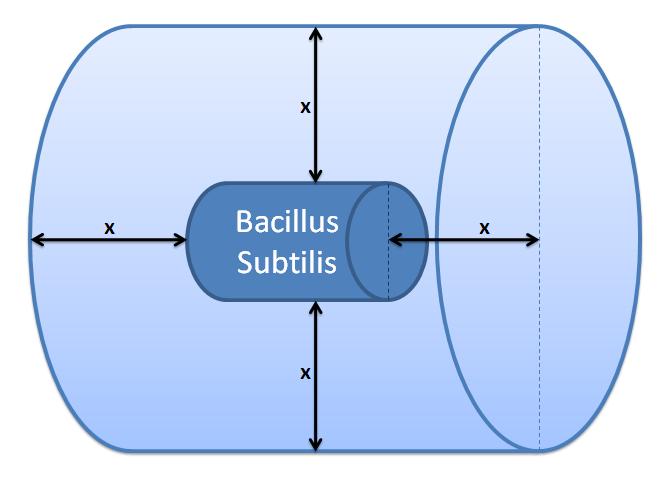

| 4. Cell Wall Volume |

|

It was necessary to calculate the volume of the cell wall as we needed it for the calculation of concentrations in the enzymatic reaction. Volume of B. subtilis is 2.79μm3 and the thickness of the cell wall is 35nm [5]. In order to approximate the cell wall volume, assume that B. subtilis is a sphere - not a rod. Calculate the outer radius from the total volume: 0.874μm. Now subtract the thickness of the cell wall from the outer radius to determine the inner radius of the sphere: 0.839μm. The volume of the cell wall is equal to the difference between outer volume and the inner volume (calculated from the inner radius): cell wall volume=0.32×10-15m3 |

| 5. Control volume selection | ||

|

Note that the product of the enzymatic reaction, AIP, is allowed to diffuse outside the cell. Hence, it is important to determine the boundaries of the system. It is worth considering whether diffusion or fluid movements will play a significant role.

Initially, we defined a control volume assuming that bacteria would grow in close colonies on the plate. We realized that our initial choice of control volume was not accurate, since our bacteria are meant to be used in suspension so we had to reconsider this issue. If you wish to have a look at our initial working, click on the button below.

Initial Choice of Control Volume

This control volume is considered to be wrong, but the details were kept for reference.

Control volume initial choice The control volume: The inner boundary is determined by the bacterial cell (proteins after being displayed and cleaved cannot diffuse back into bacterium). The outer boundary is more time scale dependent. We have assumed that after mass cleavage of the display-proteins by TEV, many of these AIPs will bind to the receptors quite quickly (eg. 8 seconds). Our volume is determined by the distance that AIPs could travel outwards by diffusion within that short time. In this way, we are sure that the concentration of AIPs outside our control volume after a given time is approximately 0. This approach is not very accurate and can lead us to false negative conclusions (as in reality there will be a concentration gradient, with the highest concentration on the cell wall).

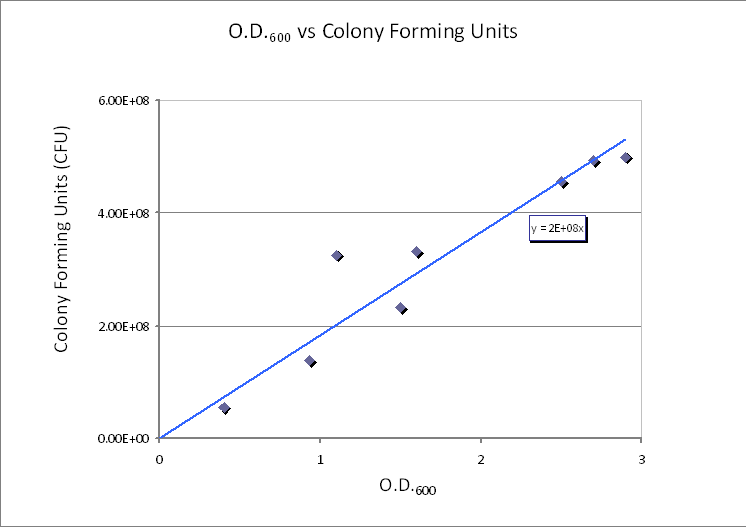

Using CFU to estimate the spacing between cells CFU stands for Colony-forming unit. It is a measure of bacterial numbers. For liquids, CFU is measured per ml. We already have data of CFU/ml from the Imperial iGEM 2008 team, so we could use this data to estimate the number of cells in a given volume using a spectrometer at 600nm wavelength. The graph below is taken from the Imperial iGEM 2008 Wiki page [4].

Side length of cubic Control volume is y = 1.26×10-4 dm = 1.26×10-5 m. Choice of Control Volume allows simplifications |

| 6. Localised concentrations |

|

Since we failed to determine a control volume across which the concentration of AIP could be assumed to be uniform, it was deduced that localised concentrations will play an important role in this model. Hence, we tried to come up with some kind of measurement of localised concentrations. Since the whole reaction happens at the cell wall and just the final product (AIP) floats around freely, we decided just to scale the AIP concentration by a factor after completion of reaction to simulate the loss of AIPs that diffuse away from the cell surface.

It was arbitrarily chosen that 20% to 50% of AIPs will bind to receptors rather than diffuse away. There are several arguments that would suggest this kind of percentage:

|

| 7. Protein production |

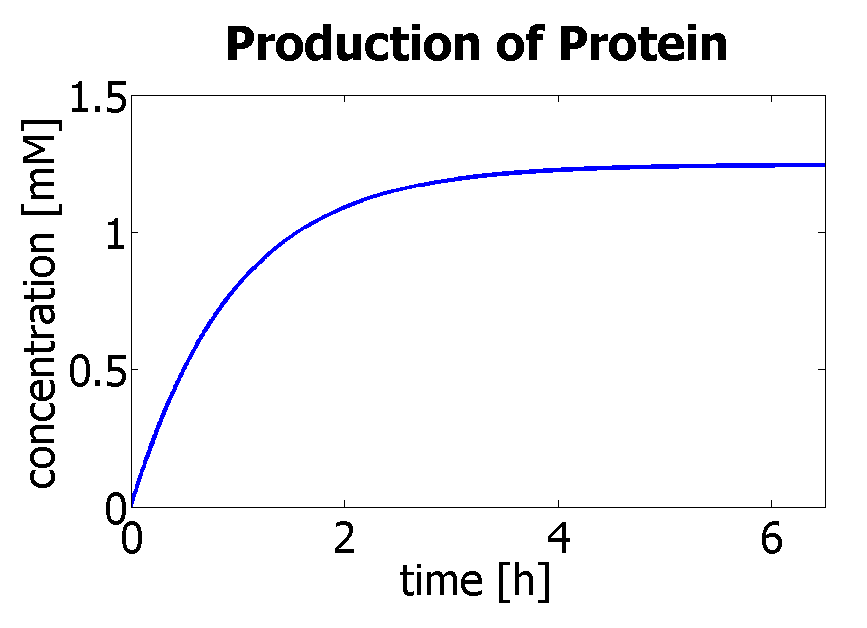

Therefore, we can model the protein production by transcription and translation and adjust the production constants so that the concentration will tend towards cfinal according to the ODE below. The degradation rate was kept constant (same as the one used in the output amplification module). This allowed us to generate the following data: |

| 8. Final version of ODE equations |

We used linear properties of ODEs presented in section 2 and 7 to combine them in the following way:

|

| Click here for the results of this model... |

| References |

|

"

"