Team:Peking/Project/Biosensor/PromoterCharacterization

From 2010.igem.org

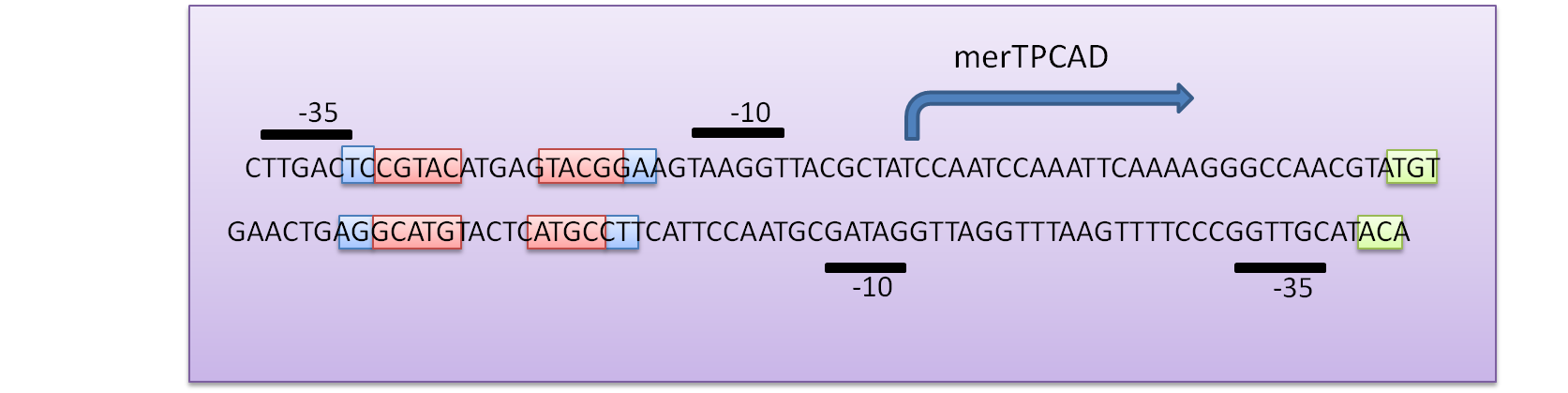

The regulatory region of mer operon consists of two tightly overlapped, divergently oriented promoters – PR and PTPCAD.(Park, Wireman et al. 1992). PR is the promoter of the regulatory protein gene, merR, and PTPCAD is for the transcription of the structure gene – merPTCAD. Both of them are called merOP as a whole. MerR always binds to merOP as a homodimer and enhances the occupancy of PTPCAD by RNA polymerase regardless of the presence of Hg(II), although only after Hg(II)’s binding can the dimer stop preventing the formation of the open complex by RNA polymerase. Also, MerR repress its own expression at Pr independently of Hg(II). In our design, merR was isolated from the operon and assembled with constitutive promoters of some strength to maintain its expression intensity at certain level. For the same reason, the divergent promoter PR was also removed by deletion of its -35 region (Fig 1).

Fig 1. DNA sequence of the Tn21 mer operon promoter region. The MerR binding site on PmerT is marked by a box. The -35 and -10 regions for both PmerR and PmerTPAD are marked with boxes, and the dyad symmetrical DNA sequence that MerR recognizes and binds to is marked with arrows under the DNA sequence. (A) The divergently oriented promoters are marked by blue box and purple box, respectively. (B) In our project, the expression intensity of MerR should be maintained exogenously, so the divergent promoter PR (of MerR transcript) was also removed by deletion of its -35 region. The resulted promoter sequence is marked with a dark purple box Modified from (Hobman, Wilkie et al. 2005)

As shown in Fig 1, the key sequence for MerR’s binding is a region of interrupted dyad symmetry (19bp) located between the -35 and -10 haxamers of PTPCAD (The top strand). And the structure of PR (botton strand) is similar to PTPCAD in a divergent orientation. The -10 hexamers of PTPCAD and PR actually overlap by four bases. (Park, Wireman et al. 1992).

Fig 2. A generalized mechanism of MerR family regulator transcriptional activation. (A) The dimeric MerR regulator binds to the operator region of the promoter and recruits RNA polymerase, forming a ternary complex. Transcription is slightly repressed because the apo-MerR regulator dimer has bent the promoter DNA such that RNA polymerase does not contact it properly. (B) Upon binding the cognate metal ions (shown as cyan circles) the metallated MerR homodimer causes a realignment of the promoter such that RNA polymerase contacts the -35 and -10 sequences leading to open complex formation and transcription. Modified from Brown et al.

The model of MerR’s action is shown in Fig 2. In (A), merR (showed as green dimer downside the DNA strand) bound to PTPCAD and recruited RNA polymerase but was unable to form an open complex. Hg (II)’s binding to the dimer changed its conformation and transcription was initiated. (Brown, Stoyanov et al. 2003)

By annealing PmerT-forward (5’-3’) and PmerT-reverse (5’-3’) primers, PTPCAD carrying a sticky end of EcoRI and SpeI was cloned upstream of BBa_E0840, a GFP generator. With exogenous expression of MerR in bacteria, GFP’s expression could be induced by Hg (II) in a dose response manner. The PTPCAD-E0840 was then cloned into pSB3K3 backbone and the BBa_J23103 (constitutive promoter)-merR into pSB1A3.

Protocols for promoter characterization

An overnight culture of bacteria carrying the two plasmids pSB3K3 and pSB1A3 were grown in LB broth with ampicillin and kanamycin at 37°C was reactivated by diluting the culture in a ratio of 1:100 with fresh LB. When OD600 reached 0.4-0.6, the bacteria was disposed to several EP tubes, each owning 500uL, and different dose of Mercuric chloride solution was supplied with 3 duplicates and the final concentration varied from 0 to 1.0E-6 mol/L. 100uL of the 500uL was added to the black-96-well plates for GFP intensity’s measurement and another 100uL was pipetted to the transparent-96-well plates for OD600 measurement. In-plate culture fluorescence and OD600 was recorded at 20min intervals from 0 to 275min and the GFP intensity of 20min before induction was also measured. Temperature was constant at 37°C.

Fig 3. Time and dose response of GFP and OD 600. The data was measured every 20 minutes since 20 minutes before supplement of different dose of Hg(II) to the wells and the plates was incubated in the shaker at 37℃during the interval of measurement. For both plates, the volume of LB medium with bacteria was 100uL per well. (a) GFP intensity was measured by Tecan Microplate Reader with excitation wavelength at 470nm and emission wavelength at 509nm. A black 96-well plate was used to minimize the interference of different well. (b) OD 600 was also measured by Tecan Microplate Reader in a transparent 96-well plate, since the depth of 100uL in the well did not reach 1 centimeter, the OD 600 value here was smaller than that was measured by a spectrophotometer.

As shown in Fig 3, the basal level of PTPCAD is relatively low. At the concentration of 5.0E-8 mol/L, the expression of GFP was observed. With longer induction time and higher concentration of Hg (II), the fluorescent intensity dramatically increased in a narrow concentration range (Fig. 3a). After the normalization by OD 600, the trend did not change obviously (figure not shown). Around 120min later, bacteria growth reached stationary phase (Fig 3-b) while GFP still accumulated rapidly (Fig 3-a). When the concentration of Hg(II) was higher than 1.0E-6 mol/uL, GFP expression level grew slower which might be explained by the saturation of MerR by Hg(II) and the cytotoxity of mercury.

Fig. 4 Dose response curve of MerR/PmerT to mercury in vivo. Note that the GFP expression intensity was induced from 10% to the maximum across a narrow range – 7 fold change in Hg (II) concentration. The basal level is low and the activation fold is dramatic. Also the metal reorganization specificity of MerR was demonstrated by the result that lead (II) could not activate significant GFP expression in vivo.

Besides, it is obvious that the MerR dependent regulation worked as a hypersensitive switch which represented negligible basal level expression of GFP, but induced from 10% to 90% of maximum in response across a range of Hg (II) concentration as narrow as 7-fold change (Fig 4). When the expression was fully induced, it was even below the threshold at which Hg (II) adversely affects the growth rate of bacterial cells. Actually, the hypersensitive switch behavior is postulated to arise from the unusual metal binding mechanism of MerR. Therefore, the molecular basis of the hypersensitivity switch will be discussed thoroughly in Bioabsorbent part of our wiki.

Aiming to analyze the PmerT promoter further, construction of merOP libriay (Random mutagenesis of the merOP) was also conducted.

Previous footprint studies [Lee, et al, 1993, Park et al, 1992] had suggested that there are three distinct domains within the palindromic merO. Mutants in domain I, which consists of the four highly conserved inner bases (---GTAC---GTAC---) of the seven-base interrupted dyad, generally allow constitutive transcription at PR. Mutants in dyad domain II, which located on either side of domain I, are semiconstitutive but support additional Hg(II)-induced open complex formation at PTPCAD (Fig. 5). In our project, we planned to analyze the behavior of merO thoroughly, and it could be expected that mutation at the dyad sequence would change the Ka of MerR-DNA interactions. Thus we mutated the semiconserved sites and left the conserved sites constant.

Fig. 5 The feature of MerR binding region, merT promoter. Semiconserved(alterable) sites are marked by blue box, conserved sites by red box, and start condon by green box. This dyadic region is located between the -10 and -35 hexamers of the structural gene promoter, PTPCAD, which is divergently.

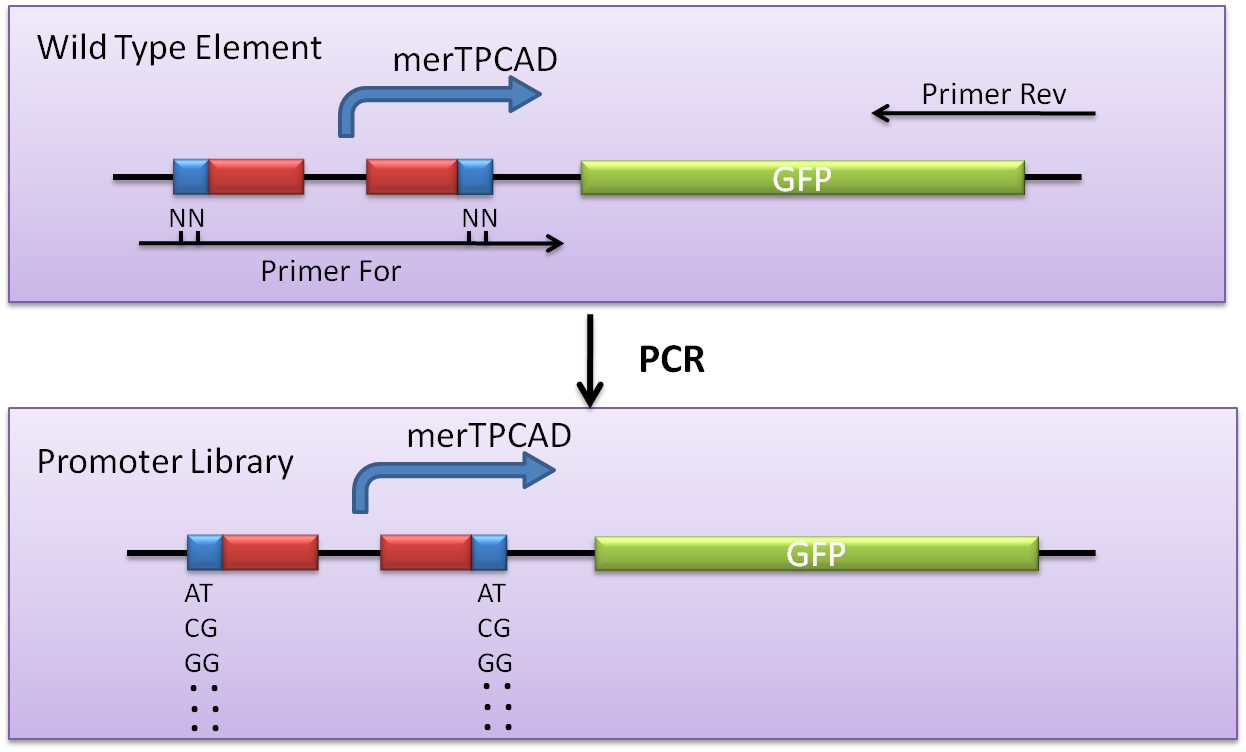

The approach was generally based upon degenerate primer PCR, with the combination of a ‘DNA shuffling’ procedure, that was performed on the target DNA sequence; the resulting library of variants was then screened for the desired feature, and selected isolates are subjected to a repeated procedure.

We performed a degenerate primer PCR on the merTPCAD wild-type promoter region of the alterable sites. The resulting PCR fragments, each potentially containing one or more random mutation sites at a restricted location, were cloned into pSB3K3 and transformed into DH5 alpha competent cells, yielding approximately 100 colonies (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Libaray construction. A saturated mutagenesis library at the alterable sites of MerR bingding site, a dyad sequence between -10 and -35 region of promoter PmerT was constructed by degenerate primers. The resulting PCR fragments, each potentially contained one or more random mutation sites at a restricted location.

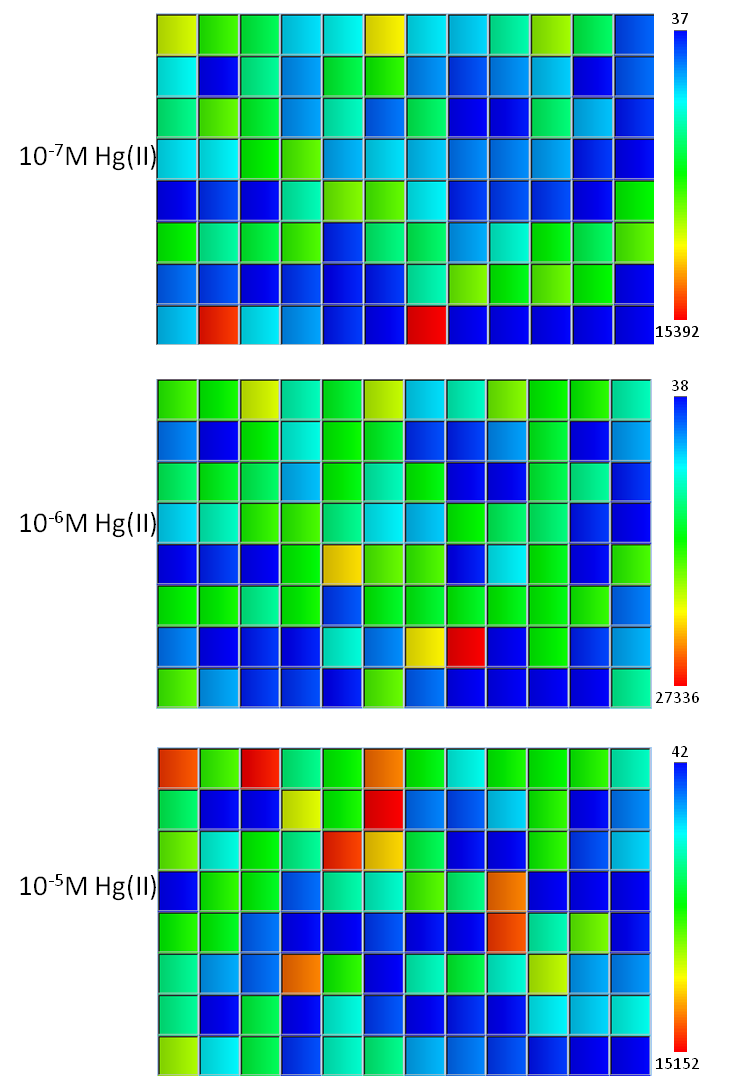

The merTPCAD (PmerT) variants library was screened and primarily characterized in 96-well plates and the performance of each individual construct was compared with that of the merT wild-type promoter.

Fig. 7 Result of secondary screen. Characterization of semiconserved region variants was performed in 96-well plates after induction with a mercury concentration gradient of 10^-7M, 10^-6M, 10^-5M for 2 hours. Wild typr PmerT promoter is marked by dotted red box and an arrow. Obviously, some mutants indeed have different response behavior compared with the wild type, for example, higher threshold.

Then secondary characterization of the best performing candidates in primary characterization was then performed in 96-well plates by induction of mercury concentration gradient of 10^-5M, 10^-6M and 10^-7M for 2 hours, followed by recording GFP intensity of each well by Microplate Reader. The result of secondary characterization showed Fig. 7.

Fig. 8 Dose response curves of each final mutants. The fitting result was shown by a solid line. Promoter sequences were shown in Table 1. Corresponding graph data were presented in Table 2.

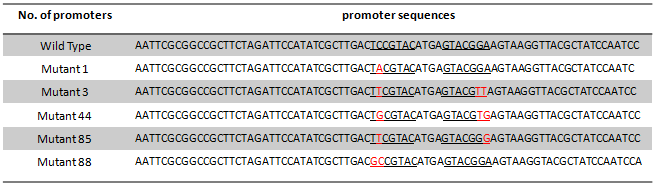

Table 1 Sequences of wild type promoter and its mutants. The MerR binding sequence is lined. The mutational sites are in red.

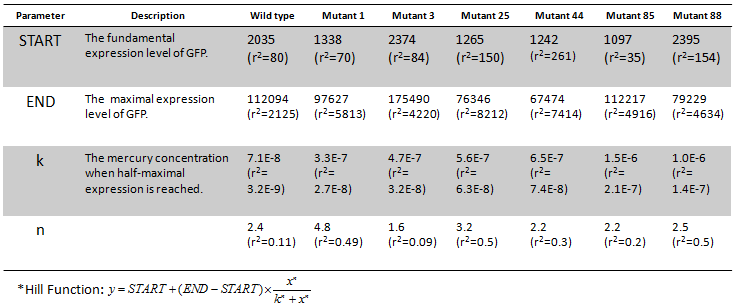

Table 2 The parameters of Hill function* fitting.

Among all these candidates, mutant1, 3, 25, 44, 85, 88 (also shown in Fig 3) were selected for the final careful characterization (Fig 8) during which a higher concentration resolution was exploited. Then the dose-response curves were fitted by Hill function (Table 2.)

It can be observed that mutations at the semiconserved region of PmerT promoter significantly influenced the response behavior of MerR/PmerT pair. It is probably because that the mutations alter the binding affinity between MerR and PmerT promoter, which can also be deduced from Table 1. As a result of this, different sensitivity (higher or lower than the wild-type) PmerT promoters were gained by us (Table 1 and Table 2).

In summary, After initially characterizing the dose-time response manner of MerR based reporter system, we constructed a saturated mutagenesis library at MerR binding site, a dyad sequence between -10 and -35 region of promoter PmerT. Shift of switch point and maxima of dose response curve was observed in dyad-sequence mutants, which shows that the binding affinity between TF and its operator site greatly influence bacterial sensitivity to mercury.

Reference

Brown, N. L., J. V. Stoyanov, et al. (2003). "The MerR family of transcriptional regulators." FEMS Microbiol Rev 27(2-3): 145-163.

Hobman, J. L., J. Wilkie, et al. (2005). "A design for life: prokaryotic metal-binding MerR family regulators." Biometals 18(4): 429-436.

Liebert, C. A., R. M. Hall, et al. (1999). "Transposon Tn21, flagship of the floating genome." Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63(3): 507-522.

Nakaya, R., A. Nakamura, et al. (1960). "Resistance transfer agents in Shigella." Biochem Biophys Res Commun 3: 654-659.

Park, S. J., J. Wireman, et al. (1992). "Genetic analysis of the Tn21 mer operator-promoter." J Bacteriol 174(7): 2160-2171.

Lee, I. W., Park, S. J., and Summers, A. O. (1993) In Vivo DNA-Protein Interactions at the Divergent Mercury Resistance(mer) Promoters. JBC. 268(4). 2632-9

Park, S. J., Wireman, J., and Summers, A. O. (1992) Genetic analysis of the Tn21 mer operator-promoter. J. Bacteriol. 174(6), 2160-71.

Lee, I. W., Park, S. J., and Summers, A. O. (1993) In Vivo DNA-Protein Interactions at the Divergent Mercury Resistance(mer) Promoters. JBC. 268(4). 2632-9

[TOP]

"

"