Team:Peking/Project/Biosensor

From 2010.igem.org

Biosensor Introduction

Sensing techniques form an integrated part of our modern life. We like to be accurately and constantly informed about the quality, security and composition of products that we consume or encounter in our daily life. Medical tests need to provide instantaneous answers on health parameters, blood values or presence of potential pathogenic organisms. Sensors come in thousand and more forms and shapes, principles and output. Future demand calls for further miniaturization, continuous sensing, rapidity, increased sensitivity or flexibility.

One of the emerging domains in sensing technology is the use of living microbial cells or organisms(van der Meer and Belkin). A biosensor is a measurement device or system that is composed of a biological sensing component, which recognizes a chemical or physical change, coupled to a transducing element that produces a measurable signal in response to the environmental change(Daunert et al., 2000). It is only since the last twenty years that living cell-based sensing assays have gained impetus and developed into a scientific and technological area by itself.

The question arises here is why one would use living cells and organisms for sensing? What are the specific purposes for basing sensing methods on living cells and what are the advantages that cellular-based sensing can have over other sensing techniques?

Testing for toxic pollution such as heavy metals is commonly performed with chemical test kits of unsatisfying accuracy (Stocker et al., 2003). Normally, costly equipment is also needed. Instead, bacterial biosensors are easily produced low cost, simple, and highly accurate devices. For example, both laboratory and field studies have demonstrated arsenic detection limits in bacterial bioreporter assays of close to 5 nM, much lower than the drinking water standard of 10 ug, making these assays ideal for analysing large numbers of samples in developing countries facing arsenic contamination of their potable water sources. Some bioreporter assays (for example, for Hg or As) have excellent measurement accuracies and compound detection specificities, and some may even compete with chemical methods. Namely, bacterial sensor-reporters, which consist of living micro-organisms genetically engineered to produce specific output such as GFP fluorescence or colors that can be distinguished by naked eyes, offer an interesting alternative for heavy metal detection.

Fig 1. Genetically engineered bacteria, tailored to respond by a quantifiable and easily recognizable signal to the presence of heavy metal, may serve as powerful tools for heavy metal detection and further assessment of the extent and the implications of environmental pollution.

Despite numerous proofs of principle, however, most bioreporters have remained confined to the laboratory (van der Meer and Belkin). As assay parameters such as induction time, cell number and cellular activity can not always be controlled in a suffciently rigorous manner; bacterial bioreporter assays on unknown samples are always performed in conjunction with a set of external calibrations. Also bacterial reporters have NOT been rational enough in design and NOT complex enough in function (Chakraborty et al., 2008; Diesel et al., 2009; Sharon Yagur-Kroll, 2010). Additionally, we notice that genetic manipulation in this field needs streamline methods (Hansen and Sorensen, 2000), which means even a limited standardization only for heavy metal biosensor construction is highly desired. It is also notable that it's time for a series of issues on the field application to be taken into consideration, such as optimization of preservation conditions of bioreporter bacteria (Kuppardt et al., 2009).

During this summer, we engineered our bacteria to resolve those hard truths mentioned above. MerR family transcription factors (TFs) was exploited to construct a series of biosensor for heavy metal detection (Hobman, 2007; Hobman et al., 2005), based on the principle of biological network control (Chikofsky and Cross, 1990).

The MerR family of proteins is a group of transcriptional factors that control metal ion, radical, and small organic molecule concentrations inside bacterial cells (Nascimento and Chartone-Souza, 2003). The MerR proteins are present in most bacterial genomes and these proteins typically regulate defensive systems against toxic or elevated levels of metal ions. Members from this protein family have been found to sense and control levels of Cd2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Cu+ , Ag+ , Au+ , Hg2+, and Pb2+ ions inside various bacteria(Nascimento and Chartone-Souza, 2003).

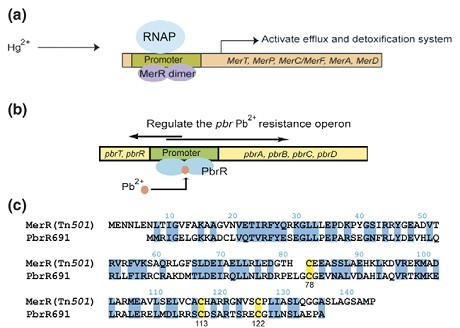

MerR is the archetype of the MerR family of proteins that detoxify mercury(II) ions inside bacteria (Fig 2). The merR gene was first identified in the transposons Tn501 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Tn21 from the Shigella flexneri R100 plasmid. In our project, MerR protein comes from the latter. MerR can recognize Hg2+ at 10^8 M concentration even in the presence of mM concentrations of small molecular thiol competing ligands(Nascimento and Chartone-Souza, 2003). The protein binds Hg2+ hundred times more selectively over other metal ions such as Cd2+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Ni2+.

Fig 2. Function of the MerR family of proteins. (a) The archetype of the MerR family of transcriptional activators is the regulator of mercury resistance (mer) MerR itself. Addition of Hg2+ to the MerR dimer leads to a conformational change of the protein that enables RNA polymerase (RNAP) to initiate the transcription of the downstream mercury(II) detoxification and efflux genes. (b) The lead resistance operon in R. metallidurans strain CH34 ( pbr) is regulated by PbrR, a protein that mediates Pb2+-inducible transcription from its divergent promoter. (c) Sequence alignment of MerR from transposon Tn21 with PbrR691 from R. metallidurans CH34. The conserved Cys residues engaged in metal binding are highlighted in yellow. Adapted from Peng Chen and Chuan He, 2008.

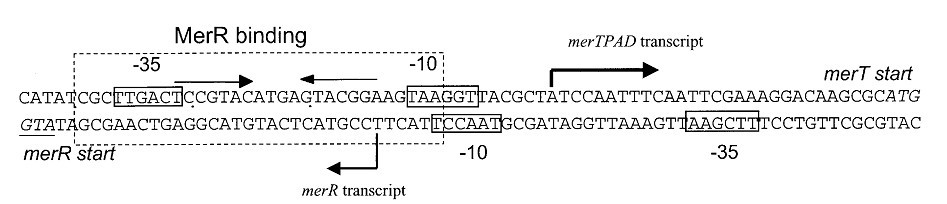

In the absence of Hg(II) and MerR, RNA polymerase preferentially transcribes from the merR promoter, increasing the amount of MerR present in the cell. Once MerR binds to merOP, transcription of the merR promoter is repressed and the DNA becomes bent and unwound at the operator sequence. RNA polymerase is recruited to the mer promoter, forming a ternary complex of DNA, MerR and RNA polymerase. In the absence of Hg(II), the MerR protein is bound to DNA in the repressor conformation maintaining repression of the promoter. Binding of Hg(II) to one of two binding sites on the MerR causes a conformational change to put MerR in the activating conformation. Due to the tight binding of MerR to the operator, this causes DNA distortion at the centre of the operator, giving a ca. 33°unwinding of DNA and straightening of helix backbone.The reorientation of the -35 and -10 sequences so caused, allows them to interact productively with the RNA polymerase δ70 subunit to form an open transcriptional complex and transcription is initiated.

The detail of the mer operator/promoter region is show in Fig.3.

Fig 3. Structure of the promoter/operator region of the mer operon of Tn21. Transcription of the mer operon in Tn21 is positively and negatively regulated by a DNA-binding protein, MerR, which binds to a region of dyad symmetry within the mer operator-prompter (merOP) region. This dyadic region is located between the -10 and -35 hexamers of the structural gene promoter, PTPCAD, which is divergently oriented relative to the MerR promoter, PR. In the absence of mercury it represses transcription of the mercury-resistance operon (merO) from a single promoter, PTPCAD, and in the presence of Hg(II) it activates transcription several hundredfold from the same promoter. It also maintains repression of its own promoter, PR.

Reporter gene expression driven by Hg (II)-binding mediated MerR transcription activation appeared in a dose response manner (Fig 4, to read more...).

Fig 4. Time and dose response of MerR to mercury. (a) GFP intensity was measured by Tecan Microplate Reader with excitation wavelength at 470nm and emission wavelength at 509nm. A black 96-well plate was used to minimize the interference of different well. (b) OD 600 was also measured by Tecan Microplate Reader in a transparent 96-well plate, since the height of 100uL in the well did not reach 1 centimeter, so the OD 600 value here was smaller than that be measured by a spectrophotometer.

The function and operation of MerR was analyzed into detail via bioware experiments and modeling. After initially characterizing the dose-time response manner of MerR based reporter system, we constructed a saturated mutagenesis library at MerR binding site, a dyad sequence between -10 and -35 region of promoter PmerT. Shift of switch point and maxima of dose response curve was observed in dyad-sequence mutants, which shows that the binding affinity between TF and its operator site greatly influence bacterial sensitivity to mercury (Fig 5, to read more...).

Fig 5. Dose response curves of each final mutants. The fitting result was shown by a solid line. Promoter sequences were shown in Table 1. Corresponding graph data were presented in Table 2.

Besides, promoters from partsregistry constitutive promoter library with different strength were prefixed before MerR coding sequence to exogenously maintain MerR expression at different intensity. The sensitivity of PmerT under different MerR concentrations can be denoted by mercury threshold concentration at which reporter (GFP) expression emerges. Data demonstrates that cells with different MerR intensity exhibit correspondingly different sensitivity to mercury, indicating that the sensitivity to Hg (II) is affected by MerR expression level to some extent (Fig 6,to read more...).

Fig 6. The expression intensity of MerR significantly determines the threshold of sensitivity to mercury (II). Constitutive promoters from Partsregistry were combined with MerR. Among the resulted response curves, five representatives are selected. It can be observed that the thresholds varied apparently with expression level of MerR. The deeper the colour, the higher expression level of the expression of MerR, leading to the higher threshold.

Our data along with those obtained from previous literature was explained and analyzed by modeling, latter of which enables us to propose a rational biosensor design. This design including GFP reporter, PmerT dyad sequence mutations and MerR expression intensity differences confers mercury biosensor high efficiency and verification in non-pathogenic Ecoli strains (Fig 7, to read more...).

Fig 7. The clustergrams of the networks We use the clustergram command in matlab to get the additional features of the functional networks. The nine vertical rectangle bar stand for nine links in Figure 2 which are, respectively, from A to A, from A to B, from A to C, from B to A, from B to B, from B to C, from C to A, from C to B, from C to C. And red stands for activation, green for repression and black for no regulation. The topologies on the right are corresponding minimal topologies that is shown in the clustergrams on the left.

Additionally, a so-called traffic light bioreporter system that can work independently of external calibration assays was also constructed from simple biosensor(Anke Wackwitz, 2008). This assay uses three isogenic biosensor strains with the same reporter output (beta-galactosidase) but differing in the mercury sensing threshold at which their reporter circuit is activated. As expected, the constructed mercury bioreporter system is capable to discriminate mercury concentration ranges at 10^-8 M, 10^-7M and 10^-6 M in water, independently of incubation time and bioreporter activity in a wide time window, more than 24 hours (Fig 8, to read more...).

Fig 8. The traffic light bioassay uses, for example, four isogenic strains with the same reporter output but differing in the compound concentration threshold at which their reporter circuit is activated. The number of reporter strains reacting to a sample (rather than their reporter signal intensity per se) is then representative for the compound concentration range.

Namely, there is no necessity to calibrate before detection assays. This means that the field application of bioreporter can be carried out without the need for costly equipment while response verification and sensor sensitivity are still kept in the near future.

Reference

Anke Wackwitz, H.H., Antonis Chatzinotas, Uta Breuer, Christelle Vogne, Jan Roelof Van Der Meer (2008). Internal arsenite bioassay calibration using multiple bioreporter cell lines. Microbial Biotechnology 1, 149-157.

Baumann, B., and van der Meer, J.R. (2007). Analysis of bioavailable arsenic in rice with whole cell living bioreporter bacteria. J Agric Food Chem 55, 2115-2120.

Chikofsky, E.J., and Cross, J.H. (1990). Reverse Engineering and Design Recovery - a Taxonomy. Ieee Software 7, 13-17.

Daunert, S., Barrett, G., Feliciano, J.S., Shetty, R.S., Shrestha, S., and Smith-Spencer, W. (2000). Genetically engineered whole-cell sensing systems: coupling biological recognition with reporter genes. Chem Rev 100, 2705-2738.

Hansen, L.H., and Sorensen, S.J. (2000). Versatile biosensor vectors for detection and quantification of mercury. FEMS Microbiol Lett 193, 123-127.

Kuppardt, A., Chatzinotas, A., Breuer, U., van der Meer, J.R., and Harms, H. (2009). Optimization of preservation conditions of As (III) bioreporter bacteria. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 82, 785-792.

Nascimento, A.M., and Chartone-Souza, E. (2003). Operon mer: bacterial resistance to mercury and potential for bioremediation of contaminated environments. Genet Mol Res 2, 92-101.

Stocker, J., Balluch, D., Gsell, M., Harms, H., Feliciano, J., Daunert, S., Malik, K.A., and van der Meer, J.R. (2003). Development of a set of simple bacterial biosensors for quantitative and rapid measurements of arsenite and arsenate in potable water. Environ Sci Technol 37, 4743-4750.

Trang, P.T., Berg, M., Viet, P.H., Van Mui, N., and Van Der Meer, J.R. (2005). Bacterial bioassay for rapid and accurate analysis of arsenic in highly variable groundwater samples. Environ Sci Technol 39, 7625-7630.

van der Meer, J.R., and Belkin, S. Where microbiology meets microengineering: design and applications of reporter bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 8, 511-522.

"

"