Team:Peking/Project/Bioabsorbent/MBPExpression

From 2010.igem.org

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

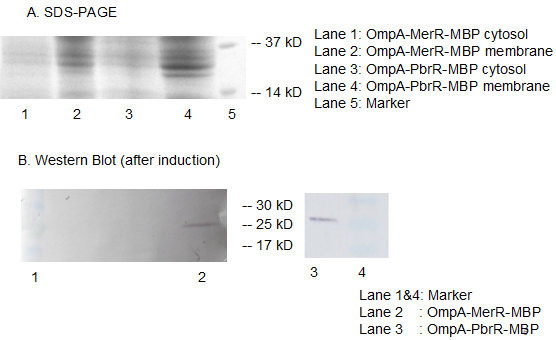

[[Image:Fig_7b.png|600px|center]] | [[Image:Fig_7b.png|600px|center]] | ||

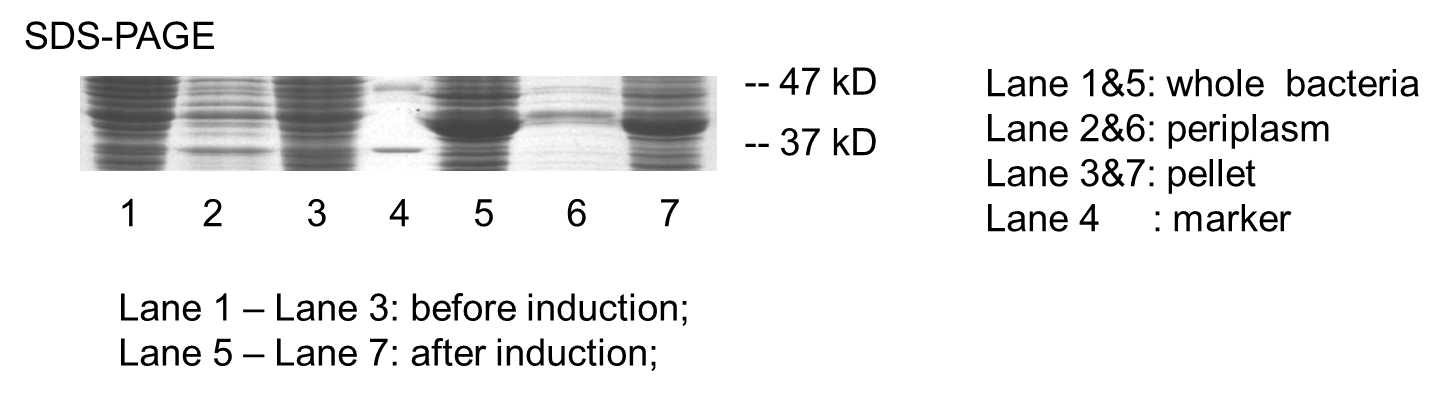

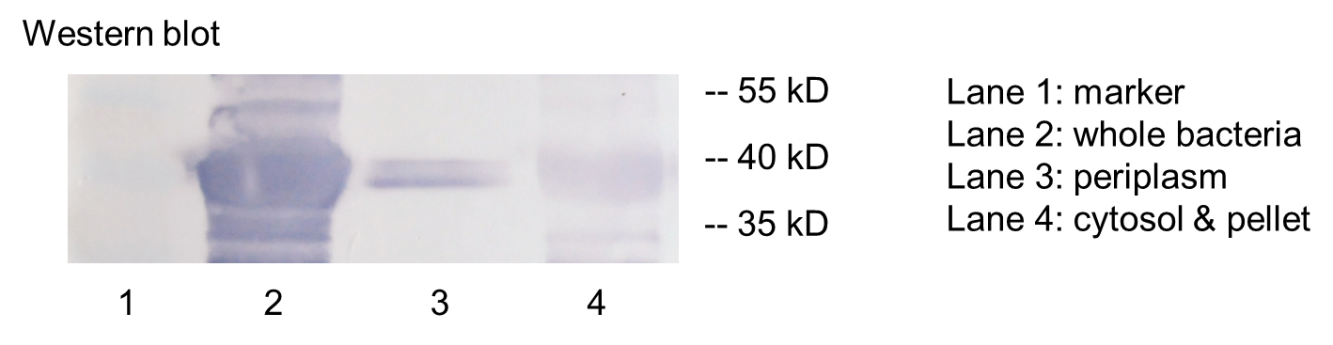

| - | '''Fig 7 Result of SDS-PAGE and Western blotting''' | + | '''Fig 7. Result of SDS-PAGE and Western blotting''' |

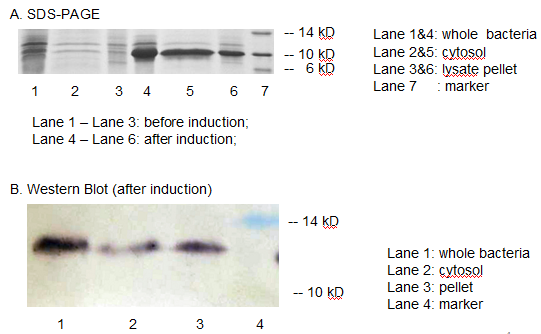

Over-expression band in SDS-PAGE result and bands specific to his-tag in western blot result were found at about 40 kD. The presence of these bands confirmed that we have got the expected protein expressed in periplasm. But there are large amount of proteins detected in lysate pellet, this was because of the high intensity of T7 promoter. When induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, our target protein were expressed so rapidly that some of them cannot fold properly and accumulated in the inclusion bodies. This problem can be solved by using lower IPTG concentration, lower induction temperature or shorter induction time. | Over-expression band in SDS-PAGE result and bands specific to his-tag in western blot result were found at about 40 kD. The presence of these bands confirmed that we have got the expected protein expressed in periplasm. But there are large amount of proteins detected in lysate pellet, this was because of the high intensity of T7 promoter. When induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, our target protein were expressed so rapidly that some of them cannot fold properly and accumulated in the inclusion bodies. This problem can be solved by using lower IPTG concentration, lower induction temperature or shorter induction time. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

[[Image:Fig_10.png|450px|center]] | [[Image:Fig_10.png|450px|center]] | ||

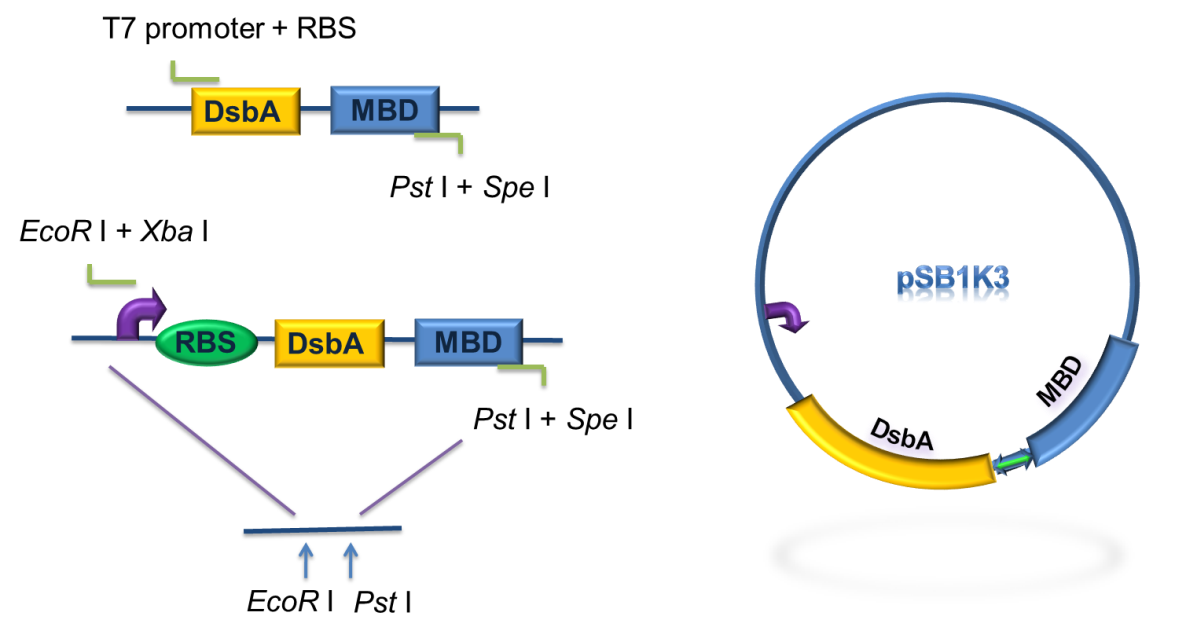

| - | '''Fig 10 Procedures of Construction of Commercial Plasmid. ''' | + | '''Fig 10. Procedures of Construction of Commercial Plasmid. ''' |

After the construction of the plasmid with the fusion protein gene Lpp-OmpA-MBP, We prefixed T7 promoter and BBa_B0030 upstream of Lpp-OmpA-MBP. Additionally, a strong terminator BBa_B0015 was suffixed. | After the construction of the plasmid with the fusion protein gene Lpp-OmpA-MBP, We prefixed T7 promoter and BBa_B0030 upstream of Lpp-OmpA-MBP. Additionally, a strong terminator BBa_B0015 was suffixed. | ||

Latest revision as of 19:43, 27 October 2010

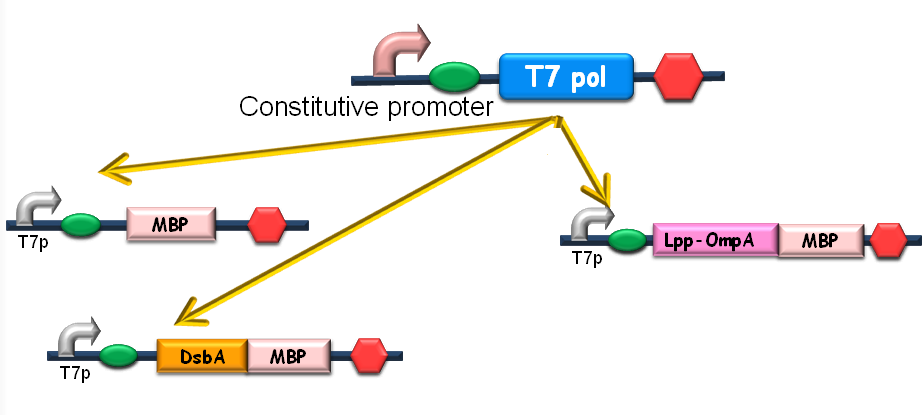

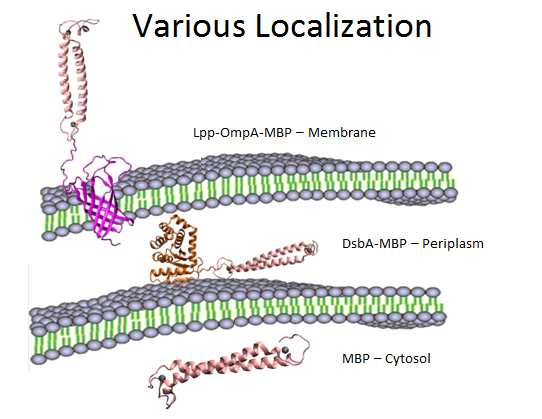

Since our ultimate goal is to design a high-performance and less energy-consuming bioabsorbent, the MBP will be an excellent candidate for the absorbent effector. MBP was then fused with DsbA, a periplasmic translocated protein with a signal sequence at its N-terminal, and OmpA, a membrane protein, to construct periplasmic MBP and surface displayed MBP, in order to maximize the bacterial capability of mercury binding. Finally, mercury MBP was constitutively expressed on surface, periplasm and cytosol of E.coli cells via carefully designed genetic circuits, to guarantee the maximum of Hg absorption (Fig 1).

Fig 1. The genetic circuit we designed to guarantee the maximum of Hg absorption. The production of T7 RNA polymerase is constitutive. T7 polymerases will active high rating transcription at T7 promoters. Thus Hg (II) will be highly effectively accumulated by substantial amount of MBPs which are translocated to cytosol, periplasm and cell surface of the bacteria.

Cytoplasmic Expression of MBP

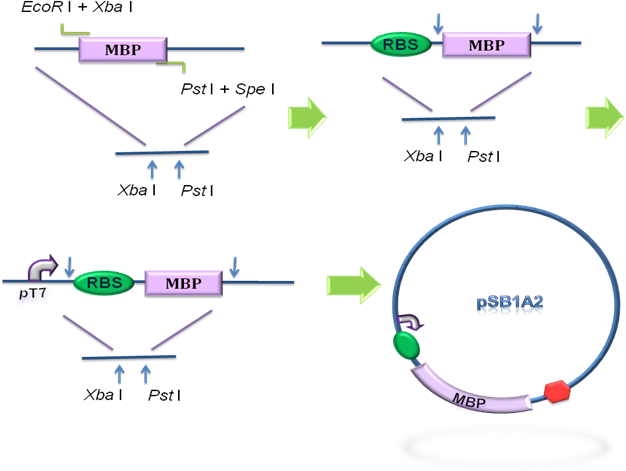

To design the module of cytosol expression, MBP in pSB3K3 was then to coloned into pSB1A2, prefixed by T7 promoter and RBS BBa_B0034 (Fig 2), verified by DNA sequencing.

Fig 2. Construction of the cytosol expression module. MBP was cloned into the pSB1A2 step by step, prefixed by T7 promoter and RBS.

The resulting construct, T7 promoter + BBa_B0034+ MBP was transformed into BL21 (DE3) competent cells. The expression of MBP has been verified by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. (Fig 3)

Fig 3. The expression of MBP has been verified by SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting. IPTG was used as the inducer. (A) Overexpression band at about 10 KD was detected. (B) Positive band of the expected molecular weight could be detected in the cytosol

We detected overexpression band at about 10 kD, which was likely to be MBP. Then we fused a his-tag to our target protein and conducted western blotting to further verify their expression. Positive band of the expected molecular weight could be detected in the cytosol, which confirmed expression and localization of the target protein. We can also indicate from the SDS-PAGE that there are indeed a large number of MBPs existing in cytosol, ready to bind mercury ions.

Periplasmic Translocation of MBP

Though contributing to the removal of Hg2+, over-expression of the mercury-binding protein may be inefficient because of its limitation of mercury uptake . Then we pay our attention to the translocation of MBP to the periplasm or surface of the bacteria, a promising strategy that not only eliminates the limitation of the capacity of accumulating Hg2+ but also makes full use of the spaces in the bacteria besides cytosolic MBPs, thus increasing the speed of absorbability and removal.

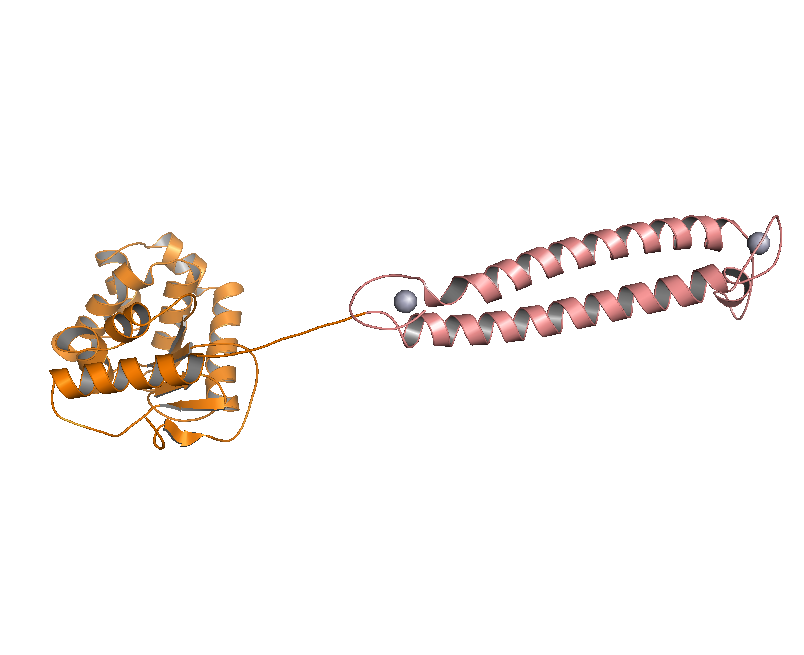

DsbA, the commonly used signal protein which can export proteins fused to it into the periplasmic space, was selected as the candidates for the periplasmic fusion MBPs. According to previous work, DsbA, a SecA dependent signal protein , can export its C-terminal fusion protein into periplasm on the signal recognition particle (SRP) pathway , which is made up of six proteins and an RNA molecule and directs rapid co-translational translocation of many proteins .Since some protein with a rapid protein folding pathway often assembles into its stable three-dimensional structure before it has a chance to be exported, Maltose Binding Protein thus inevitably suffers from its inefficient posttranslational export . In contrast, DsbA perfectly bypasses such problem due to its cotranslational translocation that obviates the inhibitory effect of protein folding on exportation. Hence DsbA overmatches Maltose Binding Protein with a more efficient and rapid way to export the target protein (for example, the metal binding peptide) to the periplasmic space, making it the best choice for the periplasmic design (Fig. 4)

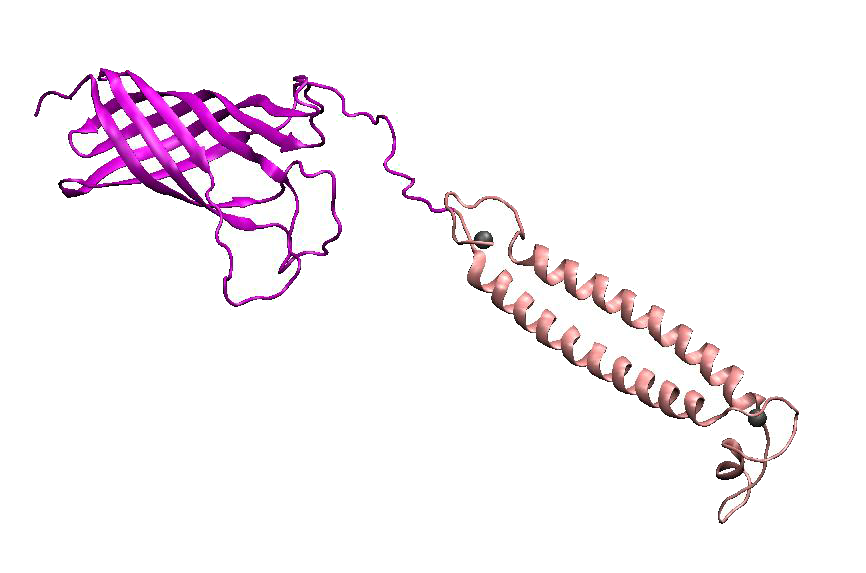

Fig 4. Result of 3D modeling for DsbA-MBP Fusion Protein. DsbA is translocated into periplasm by the co-translational pathway, which is friendly for protein folding.

Then a genetic circuit was designed as was shown in Fig 4. Bacteria will express large copy number of DsbA-MBPs and finally they will fill up the periplasmic space. In addition, RBS B0030, a weaker ribosome binding site was used as to avoid the overexpression of DsbA-MBP because it might saturate the co-translational transporter and inhibit the translocation of other proteins.

As for the standardization of the periplasmic translocation module, the entire coding region of DsbA and MBP was cloned into pSB1K3 with standard restriction enzyme sites. Particularly, the PstI restriction site inside DsbA was mutated synonymously.

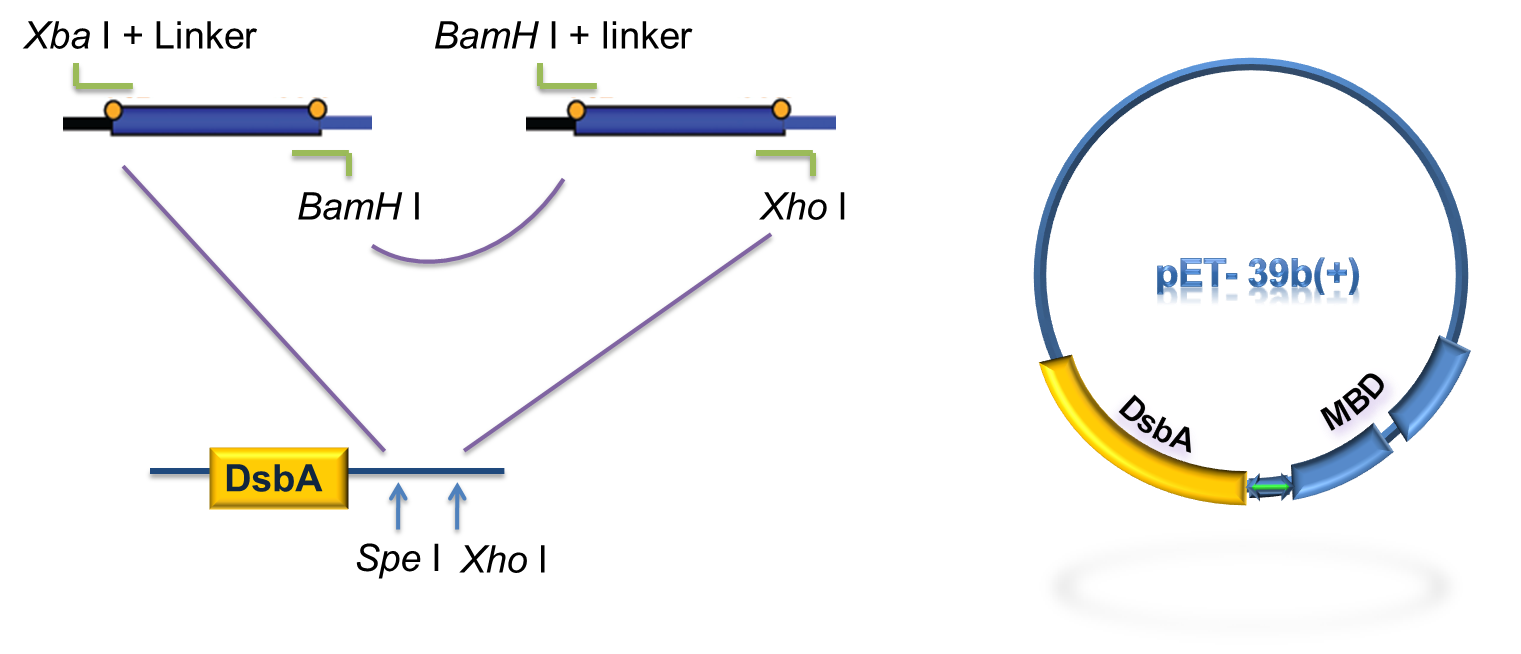

Fig 5. Procedure of DsbA-MBP construction.

As to construct the fusion of DsbA-MBP, a commercial plasmid, pET-39b (+), which contains the gene encoding DsbA, was used as the backbone. The entire coding region of the MBP was amplified by PCR from full length MerR with two pairs of primers. The two PCR products were digested with Xba I / BamH I, or BamH I / Xho I, followed by cloning these 2 fragments into Spe I / Xho I digested pET-39b(+) in one step (Fig. 5) to construct pET-39b(+)-DsbA-MBP.

Fig 6. Standardization procedure of DsbA-MBP.

DsbA and MBD gene was amplified by PCR from pET-39b (+)-DsbA-MBP, with the primer containing T7 promoter, RBS and SD restriction sites, as shown in Fig 6. The PCR product was digested with EcoR I / Pst I and then cloned into EcoR I / Pst I double digested pSB1K3, to achieve the goal of standardization of the fusion protein (Fig. 6).

RESULT

Periplasmic Expression DsbA-MBPs was verified by SDS-PAGE and western blotting (Fig 7).

Fig 7. Result of SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

Over-expression band in SDS-PAGE result and bands specific to his-tag in western blot result were found at about 40 kD. The presence of these bands confirmed that we have got the expected protein expressed in periplasm. But there are large amount of proteins detected in lysate pellet, this was because of the high intensity of T7 promoter. When induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, our target protein were expressed so rapidly that some of them cannot fold properly and accumulated in the inclusion bodies. This problem can be solved by using lower IPTG concentration, lower induction temperature or shorter induction time.

Fig 8. Lpp-OmpA-MBP was designed as a fusion protein consisting of the signal sequence and first 9 amino acid of Lpp, residue 46~159 of OmpA and the metal binding peptide (MBP). The signal peptide of the N-termini of this fusion protein targets the protein to the membrane while the transmembrane domain of OmpA serves as an anchor. MBP is on the externally exposed loops of OmpA, which can be anchored to the outer membrane.

Lpp-OmpA(46-159) fusions were proved to be an effective surface display system to anchor a variety of proteins such as ,B-lactamase [6], a cellulose binding protein, alkaline phosphatase and a single chain Fv antibody fragment(scFv)[7] on the external surface of E. coli. For OmpA, targeting and correct assembly into the outer membrane appear to be distinct events. Extensive studies on it suggest that the region between residue 154 and 180 is crucial for localization on the membrane, while the region between residue 46 and 159 ,the fragment constitute our fusion protein, contains five transmembrane β-strands of an eight-stranded β-barrel, providing an sufficient region to assemble into the membrane[6].

Additionally, a signal peptide is also needed to mediate the proper localization of the fusion protein on the outer membrane. The N-termini of the outer membrane lipoprotein (Lpp) can serve as the signal peptide, which is considered to be firmly associated with the membrane due to its extreme hydrophobicity [6]. To conclude this, the fusion protein of Lpp-OmpA , with their target and assembly function, can serve as a powerful tool in surface display [9].

CONSTRUCTION

We constructed a fusion protein consisting of the signal sequence and first 9 amino acid of Lpp, residue 46~159 of OmpA and our metal binding peptide (MBP). The signal peptide of the N-termini of this fusion protein targets the protein to the membrane while the transmembrane domain of OmpA serves as an anchor. MBP is on the externally exposed loops of OmpA. To test the expression of the fusion protein and the function, it was essential to construct both the standard plasmid and commercial plasmid.

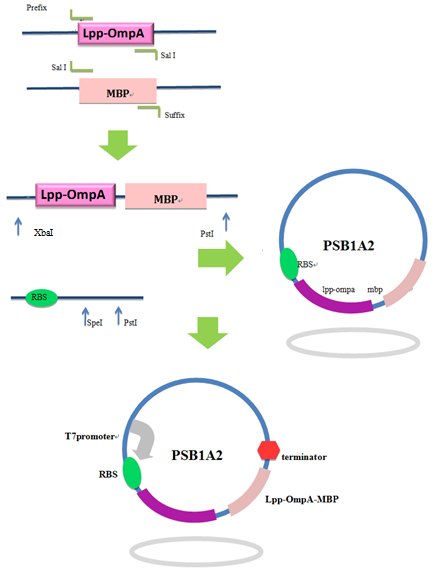

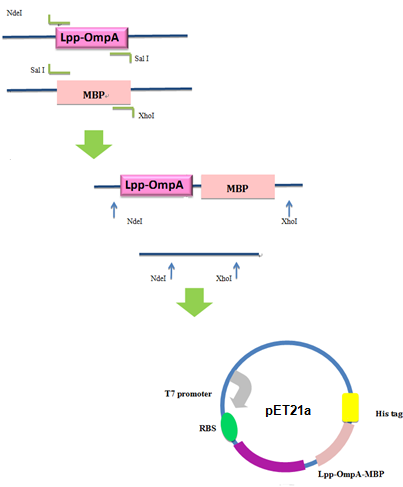

Firstly, we used PCR to obtain Lpp-OmpA gene from the template of PSD-MBD which was provided by Anne O Summers as a gift. The primers were designed based the literature (Fig 9). And the MBP gene was also obtained by PCR. Then the two fragment were cut with EcoRI(or NdeI), SalI and SalI, PstI (or XhoI), respectively, as inserts and the standard plasmid PSB1A2 was cut with EcoRI and PstI(for the commercial plasmid PET21a, the enzymes were NdeI and XhoI) as the vector. Ultimately, three fragments (Lpp-OmpA, MBP and the vector) were combined to get the standard and commercial plasmid bearing Lpp-OmpA-MBP, as is shown in Fig 9 and Fig 10.

Fig 9. Procedures of the construction of standard plasmid.

Fig 10. Procedures of Construction of Commercial Plasmid.

After the construction of the plasmid with the fusion protein gene Lpp-OmpA-MBP, We prefixed T7 promoter and BBa_B0030 upstream of Lpp-OmpA-MBP. Additionally, a strong terminator BBa_B0015 was suffixed.

Fig 11. Results of SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting. The overexpression band in SDS-PAGE and specific band in western blotting comfirmed the correct expression and localization of our fusion protein. Specific band cannot be detected in the cytosol which indicates the excellent translocation efficiency of OmpA.

Fig 12. Overview of various localization of MBP.

In summary, as is shown in Fig 12, MBP will be translocated in three different compartments in cell, directly into cytosol, into periplasm with the help of DsbA, and display on the surface using OmpA fusion. We would also like to compare the effects to evaluate the different efficacy of these modules, as is shown below.

We mainly used two methods to evaluate the capability and efficacy of our bioabsorbent:

For qualitative measurement, we invented a creative method to directly visualize the detoxification process of our bioabsorbent.

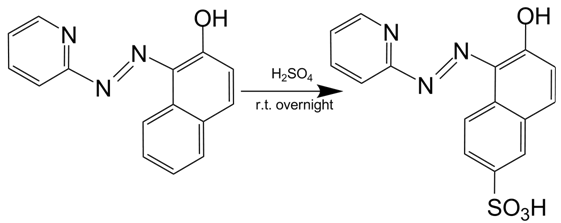

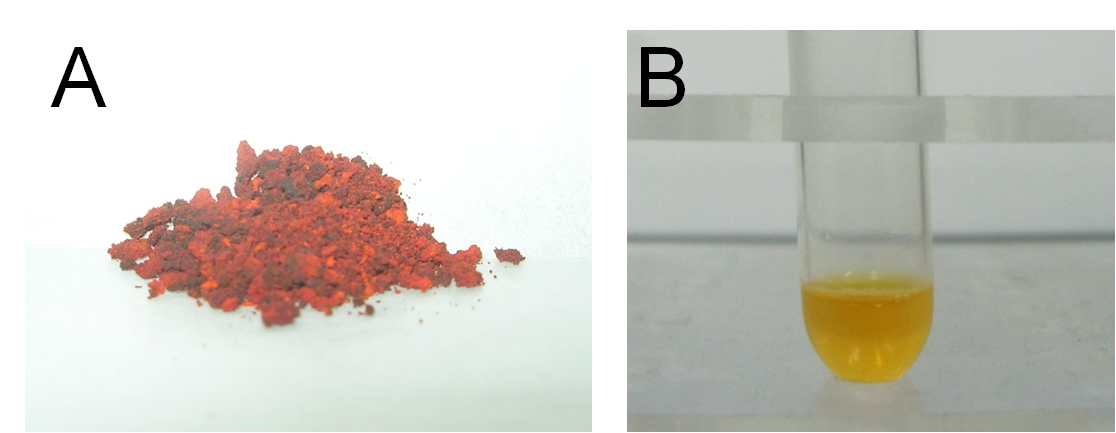

Firstly, we synthesized a water-soluble metal indicator, TritonX-100-PAN-S, according to the method in reference. [10] Treated with pure sulfuric acid by stirring reaction overnight at room temperature, 1-(2-Pyridylazo)-2-naphthol (PAN) was sulfonated to make it water-soluble. (Scheme 1) After ether sedimentation and washing, we obtained the raw product, PAN-S, which was a reddish-brown solid powder. (Figure 13A) Then we mixed PAN-S and TritonX-100 by 1:20 mass ratio, and added ddH2O for thorough dissolving to get the final working solution, TritonX-100-PAN-S (TPS), with bright orange color. (Figure 13B)[11]

Scheme 1. Synthesis of PAN-S.

Fig 13. A: PAN-S as reddish-brown solid powder. B: TritonX-100-PAN-S (TPS) as bright orange solution.

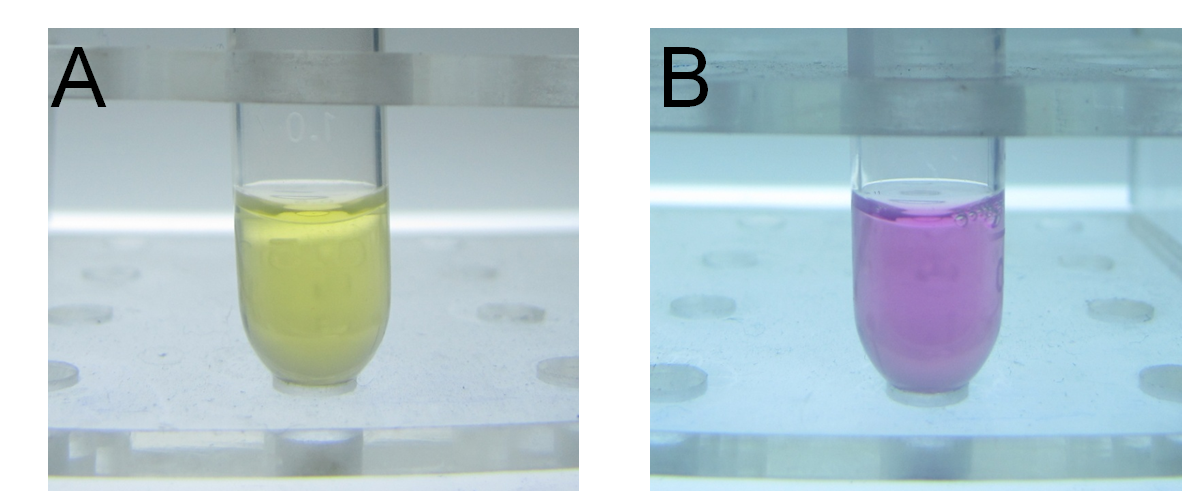

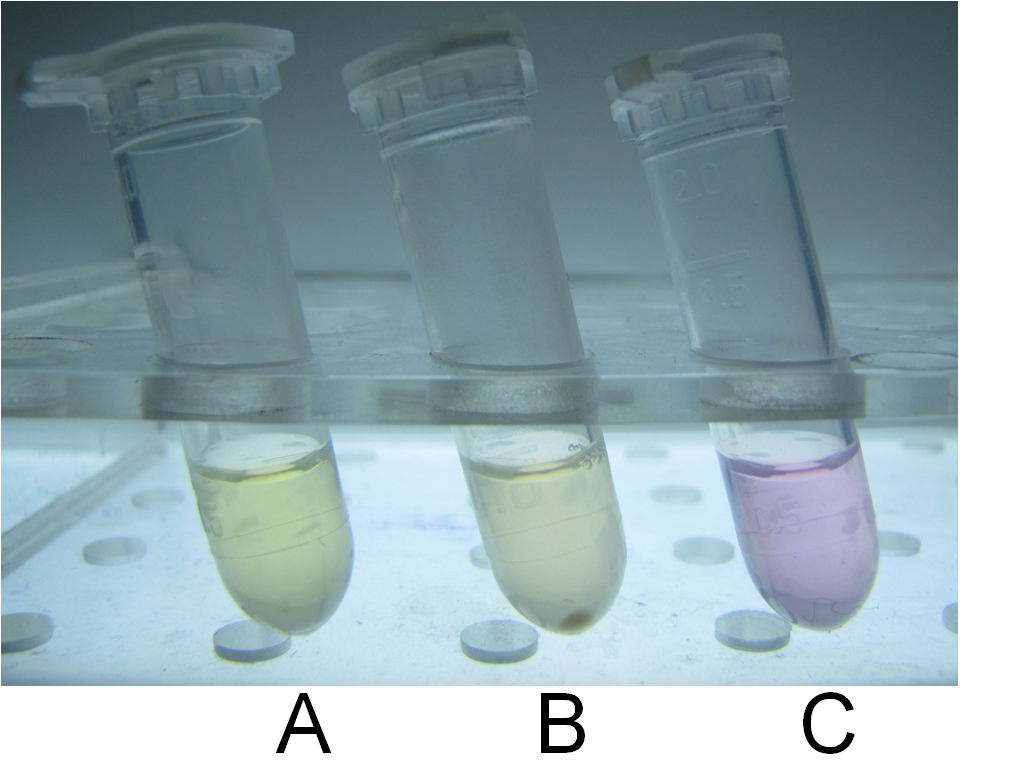

Secondly, we conducted the characterization for our self-synthesized water-soluble metal indicator with expected colorimetric selectivity for heavy metals. We started with pH and metal concentration titration. By adding TPS into different pH solution at different mercury concentration, we found the proper color transition point at pH=~8. The lower limit of metal concentration for color transition was 0.8×10-5M. The color of solution changed from bright yellow to rosy color. (Figure 14)

Fig 14. Evident color change of TPS upon addition of mercury. A: Before addition of mercury. B: After addition of mercury.

Thirdly, we used our characterized indicator for direct visualization of mercury detoxification process. We constructed an integrated plasmid consisting of a constitutive promoter and metal binding peptides localized at different cell compartments. After transformation and overnight culturing, the bacteria were used to treat sample solution with 10-5M mercury and TPS at 37℃ for 10 min. The result was intriguing. Evident distinction could be observed between experiment group and control groups, which indicated the high efficacy of our bioabsorbent. (Figure 15)

Fig 15. Direct visualization of mercury detoxification process. A: 500uL HEPES buffer +10uL TPS; B: 500uL HEPES buffer +10uL TPS +10uM mercury + bacteria bioabsorbent; C: 500uL HEPES buffer +10uL TPS +10uM mercury. Three groups were shaking cultured at 37℃ for 10 min and followed by centrifugation.

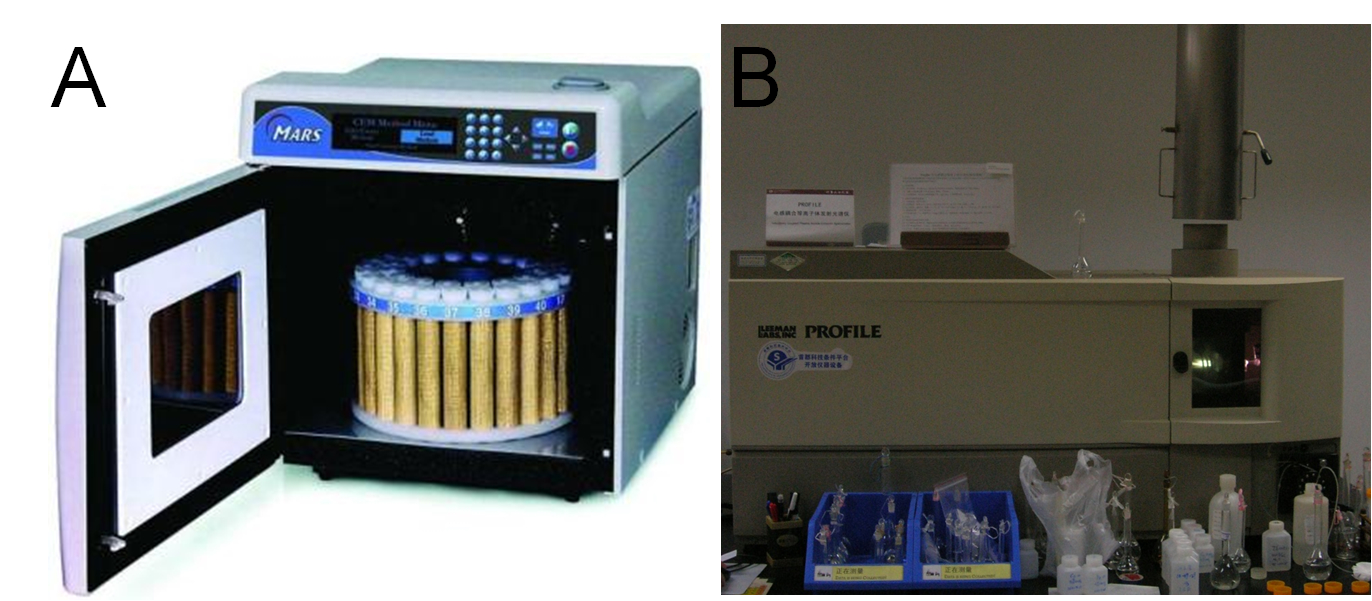

For quantitative evaluation, we used inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) to precisely measure the different concentration of heavy metal before and after the treatment of bioabsorbent.

We constructed several plasmids for different localization of metal binding peptides and transformed them into BL21 (DE3) for expression, respectively. After approximately 40 hours of induction at the presence of different concentration of heavy metals, we collected the bacteria, washed with ddH2O for several times, and freeze-dried the pellet overnight before precise measuring their dry weights. Then we performed microwave digestion to completely dissolve all metal ions into solution before ICP-AES measurements. (Figure 16A, B)

Fig 16. A: High Throughput Closed Microwave Digestion System (Mars, USA). B: Leeman Labs Profile inductively coupled plasma (ICP) spectrometer (Leeman, USA).

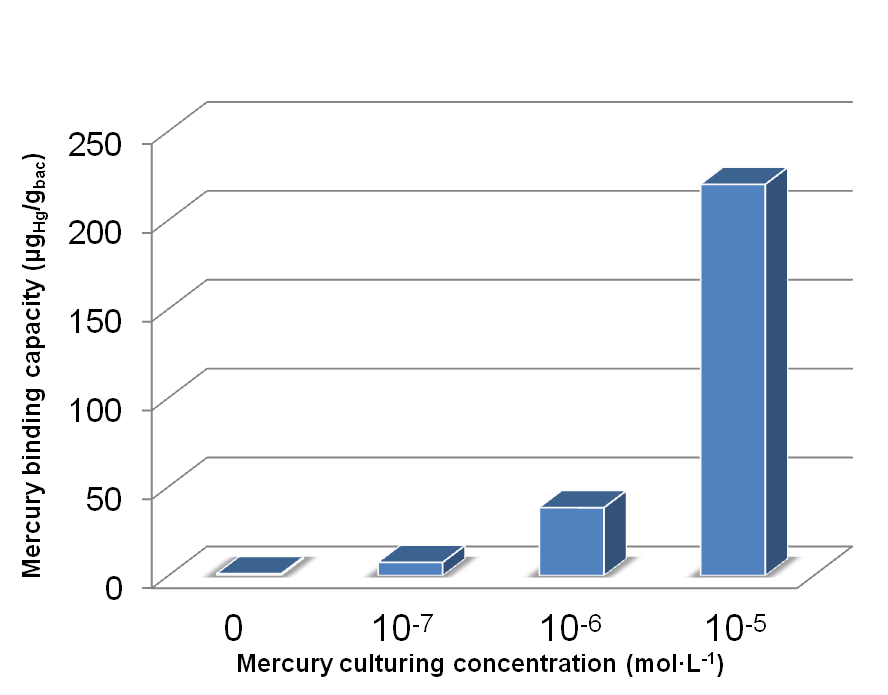

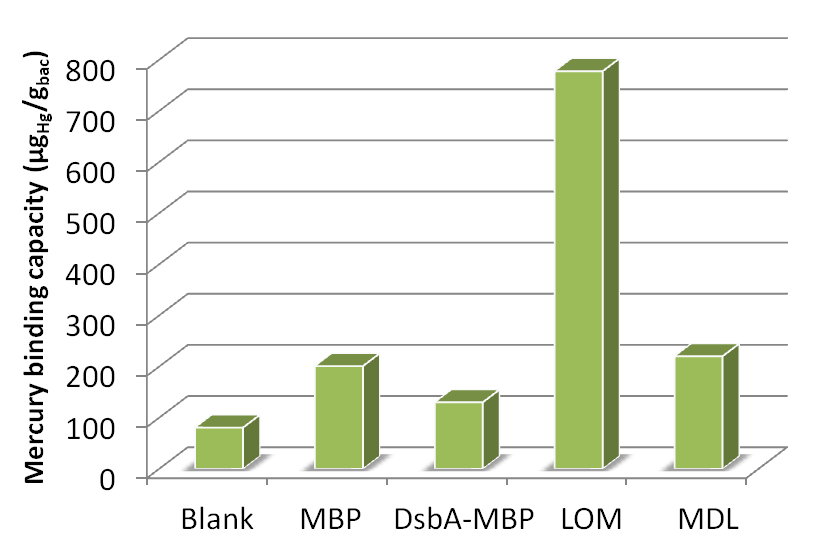

The results are shown in the following figures:

Fig 17. Different amount of mercury absorbed by bacteria with integrated plasmid consisting of MBP, DsbA-MBP and Lpp-OmpA-MBP (MDL) cultured with different Hg(II) concentration.

Fig 18. Different amount of mercury absorbed by bacteria with MBP expressed in different subcellular compartments cultured for ~40h in 10-5 mol/L Hg (II) medium.

Reference

1.Chen, S., and D. B. Wilson. 1997. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli genetically engineered for bioremediation of Hg2-contaminated environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2442–2445.

2.Chen, S., and D. B. Wilson. 1997. Genetic engineering of bacteria and their potential for Hg2 bioremediation. Biodegradation 8:97–103.

3.Chen, S., and D. B. Wilson. 1997. Construction and characterization of Escherichia coli genetically engineered for bioremediation of Hg2-contaminated environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2442–2445.

4.Luirink, J., and B. Dobberstein. 1994. Mammalian and Escherichia coli signal recognition particles. Mol. Microbiol. 11:9–13.

5.Debarbieux, L., and J. Beckwith. 1998. The reductive enzyme thioredoxin acts as an oxidant when it is exported to the Escherichia coli periplasm. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:10751–10756.

6.Francisco, J. A., Earhart, C. F. & Georgiou, G. (1992). Transport and anchoring of beta-lactamase to the external surface of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89, 2713–2717.

7.Francisco, J. A., Campbell, R., Iverson, B. L. & Georgiou, G. (1993). Production and fluorescence-activated cell sorting of Escherichia coli expressing a function antibody fragment on the external surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90, 10444–10448

8.Yamaguchi, K., Yu, F. & Inouye, M. (1988) Cell 53, 423-432.

9.Jie Qin,Lingyun Song,Hassan Brim, Michael J. Daly and Anne O. Summers(2006) Hg(II) sequestration and protection by the MerR metal-binding domain(MBD).Microbiology 15, 709–719.

10.Jingping Wang, Zhongming Wu.(2004) Simultaneous titration determination of mercury and lead with 1-(2-Pyridylazo)-2-naphthol sulphonic acid as a complexometric indicator. Chinese Journal of Analysis Laboratory 23, 60-62.

11.Min Li, Guojun Lian.(2004) The effect of TritonX-100-PAN-S as a complexometric titration indicator in determining copper. Guangdong Trace Element Science 11, 56-58.

"

"