Team:UCL London/Fermenter Mechanics

From 2010.igem.org

Fermentation set-up

Mechanical Design of 1000L Fermenter

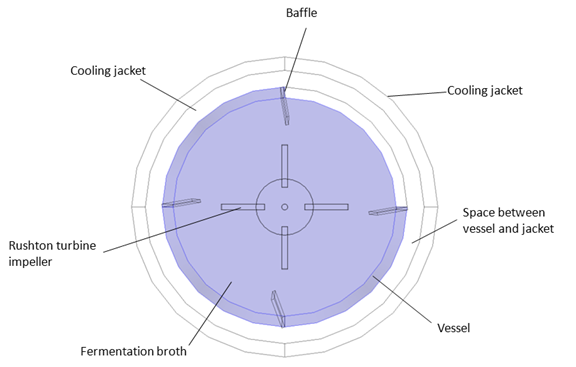

This report was conducted to estimate the dimensions and the materials needed for the construction of a 1000L fermenter for the production of Fab fragments (fragmented antigen binding) are the regions of an antibody expressed and secreted in E.coli cells. For the estimation of the dimensions of the fermenter empirical equations and rules of thumbs were exploited. The dimensions and the fermenter properties like the diameter, the height as well as the impellers speed, the baffles position and the driveshaft size were estimated on a scale- down model. The material used for the fabrication of the fermenter, the head end, the ports and the pipes is stainless steel to resist corrosion and maintain a clean and sterile vessel. The diameter of the vessel is 0.8m and the height is 2m.

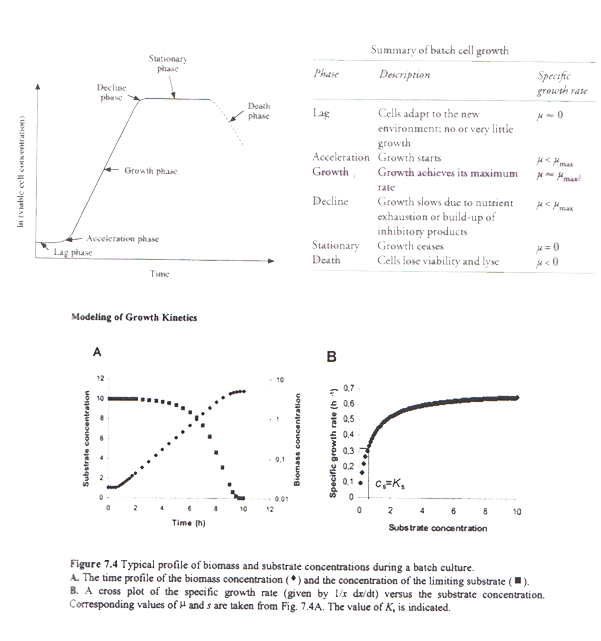

The thickness of the wall is 6mm with a 0.15 m jacket surround it. The impeller’s speed is 3.3 m/s and the impeller used is Ruston Turbine four blades, suitable for the growth of E.coli cells. Therefore all the power requirements were satisfied ensuring the viability of the design. Five spray balls were found to be enough for a sufficient cleaning of the fermenter with their 360° coverage and placed on the inside of the torispherical head in a cross shape. Then the flowrate in the pipes was predicted enabling the calculation of the diameter. Basically all the information specified for every single part of the fermenter was taken from recommendations, advice from experts, theoretical predictions as well as engineering justifications. Last but not least emphasis is given on the importance of maintenance and annual shutdowns of the plant as well as regular checks to ensure its proper operation. The above graph, show the phases in the cell growth in a typical batch. The table, describes each phase and provides the specific growth rate for each phase. Reproduced from P.M.Doran (2006), pp:277

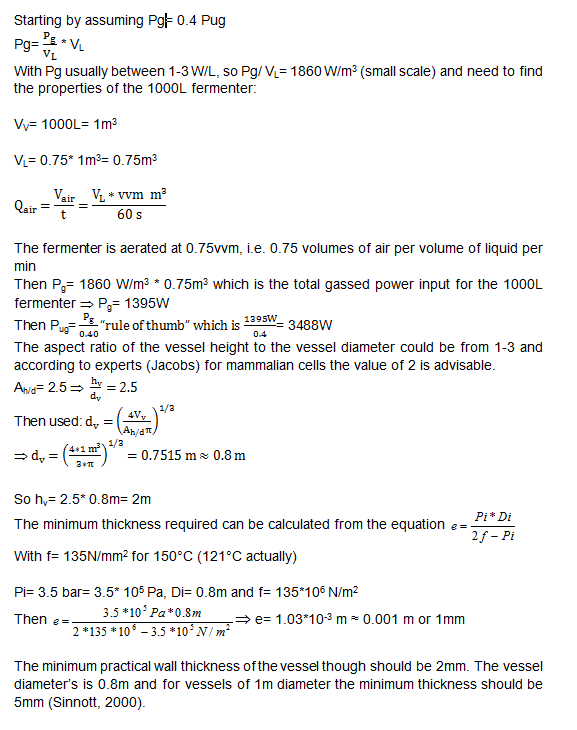

The above graphs, show the modeling of the growth kinetics and the typical profiles of biomass and substrate concentration during a batch process. Reproduced from Nielsen et al (2002), pp:247

Operation Cycle

The operation cycle for the fermenter involves start up, where process water is fed from the process water port and media is fed from the feed port into the vessel. The level of the liquid is measured using the level indicator probe. Once the required level is met then the ports close. Air is pumped through the air inlet to the sparger inside the fermenter.

The temperature is brought and maintained to the optimum temperature. There are two probes in the fermenter which are at the greatest range i.e. opposite sides of the fermenter as shown in the drawing. This is to ensure the distribution of heat is even and the average of both sensors should read 37°C. The pH is maintained at a desired value by the addition of acid and alkali. Two probes for measuring the pH are placed inside the fermenter at opposite ends to ensure there is good mixing as this would be indicated if there was little change between the two probes.

Once the optimum conditions have been achieved the innocculum is fed through the innocculum port. Antifoam from the antifoam port is added to avoid foam formation which reduces the efficiency of the process. The exhaust gases are released from the fermenter whilst in operation and the pressure is maintained. The cells are grown for a certain period of time and the process is regulated using a series of automatic control loops.

Finally there is shut down, where the fermentation batch ends and in this step all the broth is collected into the harvest port.

After each operation cycle the fermenter will have to be cleaned and sterilized in place. CIP will be performed using acid and base detergents which will be pumped through the cleaning solution ports into the 3 spray balls. SIP requires that the fermenter and all pipes are sterilized with steam at 121°C. The steam will come from the acid, base and antifoam ports. Regular and annual maintenance checks will have to be performed to ensure everything is running correctly and as efficiently as possible.

Maintenance

Typically, 3-5% of fermentations in an industrial plant are lost due to failure of sterilisation procedures. However in antibiotic fermentations like in this project, fewer than 2% of production scale antibiotic fermentations are lost through contamination by microorganisms or phage. (Doran, 1999)

Industrial fermenters are designed for in situ steam sterilisation under pressure. For effective sterilisation, all air in the vessel and pipe connections must be displaced by steam. After sterilisation, all nutrient medium and air entering the fermenter must be sterile.

Maintenance is required to ensure the fermentation process is achieving its goals, to identify any problems that may occur and ultimately keep the process working as efficiently as possible to save on costs. Maintaining the fermenter can significantly reduce the overall operating cost as well as minimise the risk of any hazards. For maintenance, the top of the fermenter can be removed to allow access of maintenance personnel for any repairs that may be required. For large vessels a domed construction at the top to allow access to personnel is less expensive and so this has been chosen in the design (Doran, 1999).

Once the design has been built and approved by British Standards 5500, the fermenter can then start to operate (Sinott, 1999). Maintenance is crucial and the fermenter must be monitored at all times. Most measurements can be made on-line through probes in the vessel which are sensors that detect changes in many variables such as temperature and pH. However, whilst monitoring some values there may always be a delay. For example, in a typical fermentation, the time scale for change in pH and dissolved-oxygen tension is several minutes to make sure they are all correctly calibrated and functioning properly and as efficiently as possible. This is to avoid any problems that may be caused because of a false reading. For example if the pH probe is not working properly and the pH is either too high or too low, then the cells would die and also the product may denature. Also possible blockages in pipes or broken valves must be checked regularly. Oxygen supply through bottom sparging should also be checked regularly, as cells die without it and that would mean a significant loss in time and money if the fermenter has been running for several days.

The fermenter requires annual shutdown to check for possible corrosion on the internal surface and also on the impellers. Corrosion may reduce the speed and efficiency of them impellers and the shaft too. This needs to be maintained at a high standard to ensure good mixing in the fermenter for growth of cells and product. Baffles also need to be checked for to see the level of corrosion. Also there may be possible fouling in the jackets and general piping problems, such as blockages and leakages, as well as overall contamination in the system. As previously mentioned in the design a 2mm allowance for corrosion had been added on the thickness of all equipment. The annual check would see how much all the equipment has been eroded and identify any problems to resolve them.

The aim of the Mechanical Drawing is to provide a detailed analysis of the construction and operation of the fermenter that is a technical way of presenting this piece of equipment. In this section the dimensions and materials of construction of a 1L fermenter were estimated. The fermenter is used for the growth of Escherichia coli cell culture for the production of therapeutic fragmented antibodies.

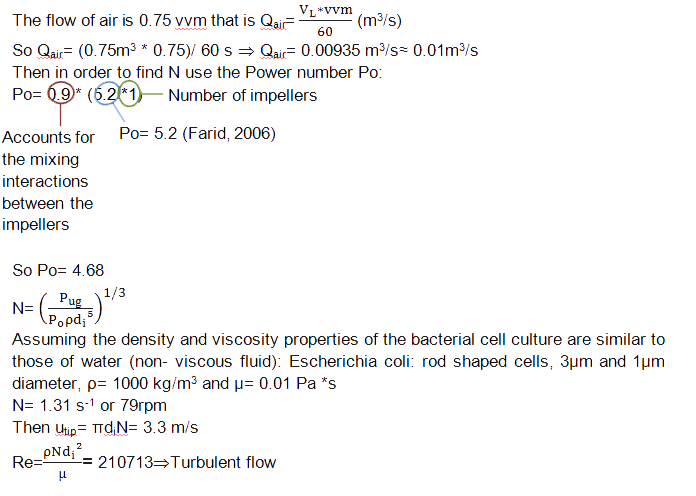

For the design project purpose several assumptions had to be made. The first one was the model taken for the scale- up process. This was the original 1L fermenter used for the pilot scale of the E.coli cells. Assuming that a 1000L fermenter operating with 75% space efficiency (0.75) and 1 marine impeller (di=dv/2). The vessel aspect ratio is 2.5 that is Ah/d= 2.5 and the fermenter is aerated at 0.75 vvm (that is 0.75 volumes of air per volume of liquid per minute). The gassed power requirement per m3 is Pg/VL= 1860 W/m3 as it was found from the model used for the scale- up. Usually the industrial motors are used to deliver 1-3 W/L (Lye et Baganz, 2007). Therefore the 1.86 W/L was chosen on the assumption that due to engineering cell modifications, the E.coli cells are not so robust and thus extremely high power inputs should be avoided. For this purpose instead of using a marine propeller a lighter choice was preferred since the Chinese Ovary cells are susceptible to mechanical damage (Farid, 2006) due to their large size and lack of rigid cell wall. Therefore the power input value must be kept to a minimum. A Rushton turbine four blade impeller is used as the axial flow type of impeller ensuring medium speed and ensuring medium growth rate but also good mixing.

Calculations for determination of the fermenter’s properties

The operating pressure of the vessel was assumed to be 3.5 bar and the design pressure 3.85 bar. The operating temperature for mammalian cells is 37°C (Lydersen et al, 1994) but the design temperature is 4- 121°C allowing the introduction of steam to clean the vessel.

Since the mammalian cells are very sensitive, an elevation in temperature e.g. 40°C can cause cell damage and death. Hence temperature probes allowing 〖_-^+〗0.5°C from the temperature set point as well as pH probe to maintain the appropriate range was considered.

Jacket

The space between the jacket and the vessel is estimated based on the size of the jacket. According to Sinnott (2000) the size of the jacket is 50mm for small vessels and 300 mm for large vessels. The assumption made is that the jacket’s size should be: 150 mm for the 1000L fermenter.

The jacket surrounding the fermenter will be made out of stainless steel 304 and its thickness is the same as the fermenter. The wall thickness of the fermenter was estimated to be 6mm based on rules of thumb including an additional 2mm allowance for corrosion.

Impeller size calculation

Then the diameter of axial mixers was based on the empirical statement (Lye, 2006) that is over 0.33 to 0.5 the tank diameter. So assumed to be 0.45 timed the diameter of the vessel, that is dm= 0.45* 0.8m= 0.36 m and the spacing is usually 1-2 impeller diameters of 1 tank diameter (Lye, 2006).

So spacing, based on 1.5xdT=0.36x0.8m = 0.3m impeller spacing of one impeller from the other.

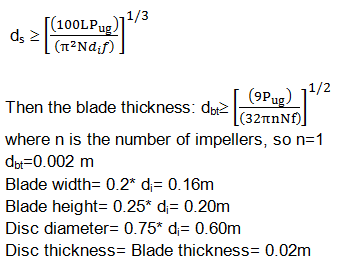

Impeller Speed and Reynolds number estimation

Driveshaft & Blades Size calculation

Then the impeller driveshaft was decided to be bottom driven as this is recommended in small industrial scale production where the shaft is shorter, gives better power development leaving more space on top plate for ancillaries with only one drawback of a more difficult seal arrangement (Lye et Baganz, 2007).

The shaft diameter was calculated by the inequality below.

The shaft length was assumed to be 1.65 m (slightly above the liquid’s level). f is the design stress which is taken from literature which is 175 N/mm2 for stainless steel 316L working at 37°C. The shaft diameter found is 0.07 m.

Baffles

It was decided that four diametrically opposed baffles would be put in the vessel. The size of each baffle should be 0.1- 0.05 tank diameter. The assumption made here is that the baffle’s diameter= 0.1*dT= 0.1 *0.8m= 0.08m or 8cm. The baffle height is dependent on the gas holding or it accepted to be equivalent to the cylindrical height of the vessel. In this case it was assumed to be slightly above the liquid’s level. Small gap between vessel and baffle is recommended to stop biomass build up, enhance oxygen transfer and cleaning solution (Lye et Baganz, 2007). The gap is 0.1 of the baffle width fixed to the vessel such that they can be removed. Also it is recommended that baffles are placed at an angle as with were found from experts to enhance scouring (Lye et Baganz, 2007). The dimensions of the baffles were estimated based on empirical equations relating their size to the vessel’s size.

Therefore in the mechanical drawing the baffles were drawn at an angle of 10° to the vertical pointing anti- clockwise since the flow direction is clockwise. That was decided after some thought and with the preparation of a computational fluid dynamic model to predict the flow of the fluid. Also the base of the cylindrical vessel was chosen to be rounded at the edges since in this way it discourages the formation of stagnant regions.

Orifice Sparger

An orifice sparger was placed under the bottom impeller and its size was calculated to be 75% the impellers diameter that is 3.375 cm (4 cm for easier design). The holed on this circular ring must not exceed 6 mm and therefore for design calculations their size was assumed to be 5 mm. A magnetic drive was chosen as the driveshaft seal as this is more common in non- viscous fermentation broths like mammalian cell culture which is a very dilute culture since the cell density is low. Although since it is placed at the bottom of the fermenter can cause cellular disruption it is an easy seal as separate parts and the shaft does not penetrate the vessel. It is made up from one driving magnet and one driven magnet and it is clearly seen on the drawing.

Design of closure for the fermenter

It was decided to use a standard torispherical head since it is widely used in industry and can withstand operating pressure up to 15 bar. The bending and shear stresses were taken into consideration in the design of the heads. For the estimation of these stresses usually caused by dilations of the vessel a basic equation used for a hemisphere was used. The knuckle and crown radii were found from empirical values allowing the stress concentration value determination that allowed with its turn the estimation of the thickness of the head.

Cs= 1/4 (3+√(R_c/R_k ))

where Cs is the stress concentration factor taken to allow for the increased stress due to the discontinuity. Rc= crown radius (not to be more than the vessel’s diameter) Rk= knuckle radius The ratio Rc/ Rk should not be less than 6% (to avoid buckling).

e= (P_i R_c C_s)/(2fJ+P_i (C_s-0.2)) For formed heads (no joints in the head) J=1.0

Pi is the internal pressure and f is the design stress (literature value). The design pressure= 110% of the operating pressure (Coulson and Richardson, 2000)

In this case, the fermenter is operating at 3.5 bar therefore the design temperature is 3.85 bar. Operating temperature= 37°C mammalian cell culture, cleaning solution 4°C for the cooling water and 121°C for the steam (CIP)

f= 135 N/mm2 (stainless steel corresponding to operating temperature 150°C) Rc= 1.5 m hence Rk= 0.06*Rc So Rk=0.09 m So e= 7 mm (5mm+ 2mm for corrosion allowance)

For design purposes it was assumed that the wall thickness and the end thickness are the same, 6mm. Basically, the wall thickness has an impact on the overall heat transfer coefficient while the end thickness affects the mixing characteristics of liquid inside and since the vessel is metal, the value of the thickness means it would aid cleaning.

Calculation of the dead weight of the fermenter

For preliminary calculations, the approximate weight of a cylindrical vessel with domed ends and uniform wall thickness can be estimated with the following equation:

W_v=C_v 〖πρ_m D〗_m g(H_v+0.8D_m )t Where Wv is the weight of vessel

Cv is a factor for the weight of nozzles etc= 1.08

Dm= Di+t where Di is the internal mean diameter of the vessel

For steel vessels the above formula becomes:

Wv=240CvDm(Hv+0.8Dm)t

All the ancillary equipment attached to a tall vessel will subject the vessel to a bending moment if the centre of gravity of the equipment does not coincide with the centre line of the vessel according to Coulson and Richardson. The moment produced by small fittings e.g. ladders, pipes and manway will be small and hence can be neglected. For this mechanical drawing though the moment equation is only being mentioned. M_e=W_e L_o where Me is the moment, We is the dead weight of the equipment and Lo is the distance between the centre of gravity of the equipment and the column centre line. From calculations, Wv= 3.2194 m3 say 3.3 m3 (3300 L or 3300 kg).

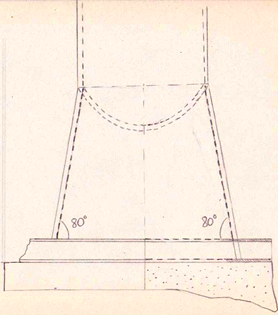

Fermentation Support with skirt

The choice of skirt support was based on that skirt supports are used for tall, vertical columns to carry the weight of the vessel and contents. Therefore the vessel support should be designed not to impose any localized loads on the vessel wall and to allow easy access to the vessel and fittings for inspection and maintenance. A flange at the bottom of the skirt transmits the load to the foundations. Last but not least, the skirt that the fermenter will be placed in was chosen to be a conical one with the angles of the base to be 80° as it is predicted to equally distribute the weight of the fermenter and ensure no collapse and balance of the whole equipment system. The minimum thickness should not be less than 5mm. Assume to be 9mm.

The stresses in the skirt can be found by calculating other outside parameters that influence the vessel’s stability besides the dead weight of the vessel or the size of the vessel with its contents like the wind loading and the earthquake acceleration. These can be found by measuring the wind speed, the density of air and hence calculating the pressure of the wind on the vessel which in turn can be used to find the stress acting directly to the fermenter. For the purpose of this study though these parameters where neglected.

Pipe dimensions

The diameter of the pipes connected to the fermenter for the air supply, air exhaust, inocculum introduction and media feed as well as the ports for the introduction of acid, alkali and anti- foam when necessary were calculated based on predicted flowrate and on the Reynolds Number representing the type of flow needed for each case. Due to the not so high operating pressure the process pipes are thin cylinders with a thickness of 2.5 mm. For the determination of the pipe dimensions turbulent flow is assumed with the Reynolds number to be > 104 to enhance good mixing of each fluid with the broth.

As a rule of thumb, liquid velocities are usually in the range 1-3 m/s in order to minimize the presence of stagnant unmixed pockets of fluids but also to extend the lifetime of the systems (Farid, 2006). Therefore assume v= 2 m/s. The mass flow, based on values (Farid, 2006) used in industry was assumed to be 10 kg/s.

"

"

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook UCL

UCL Flickr

Flickr YouTube

YouTube