Team:Monash Australia/Modelling

From 2010.igem.org

|

|

|||

Contents |

Introduction

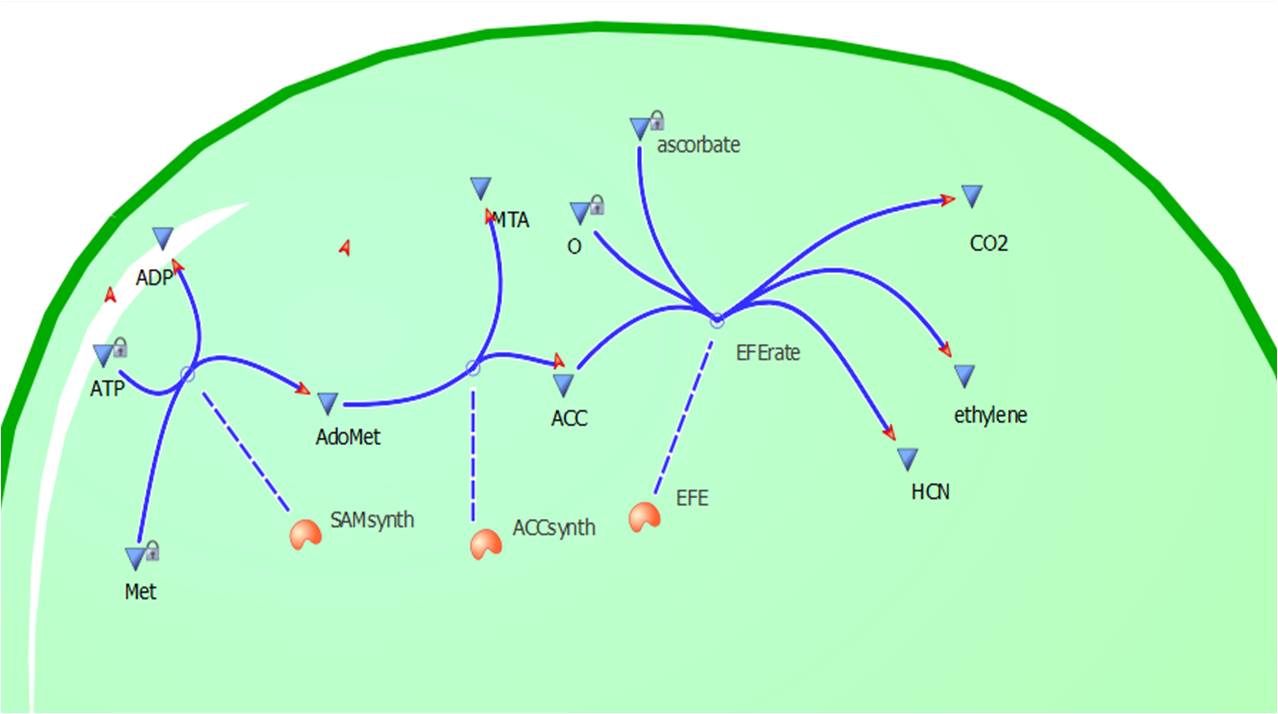

The three key enzymes we require are outlined in the image Figure 1 (left), SAM synthase, ACC synthase and ACC oxidase. SAM synthase converts methionine into S-Adenosyl-L-Methionine (SAM), using ATP for an adensoyl group. The second step involves ACC synthase, which cleaves the amino butyrate from SAM, releasing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC). Released ACC is then processed by ACC Oxidase which converts ACC to ethylene by cleaving the carboxylic acid off as carbon dioxide and its neighboring carbon with the amino group as cyanide gas. By using such a system to produce ethyene gas we can potentially reduce costs involved with current production methods by reducing temperature requirements by 30 fold.

Kinetic modelling of the ethylene generator

The program tinkercell was used to model the synthesis of ethylene in our E.coli cells. Where, in addition to the qualitative representation (figure 2 & 4) the program allowed, simulation of the model could be exercised inorder to measure the flux of metabolites – with respect to time - in the system given the input of values pertaining to substrate/enzyme concentration, and reaction rates were inputted. Figure 2 or Model 1 was designed to include fixed concentrations at a steady state ratio of 1:1:1. This design ensured sensible approximate values of ethylene output were obtained given the correctness of enzyme rates and other parameters used.

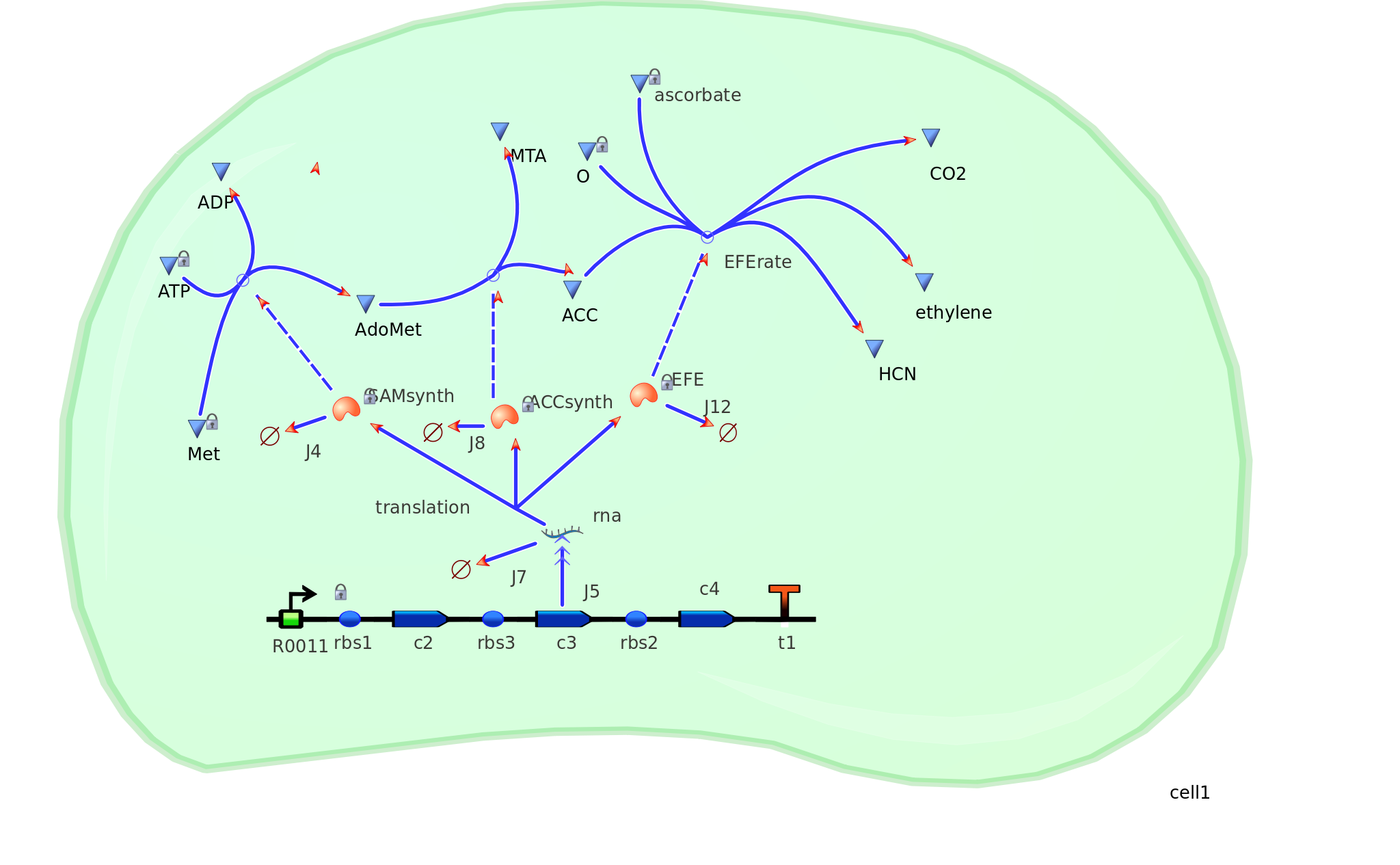

Adapting on to model 1, quantitative data in silico corresponding to mRNA transcription, protein translation, and degradation were implimented into a more complex design - giving model 2. As a result, more realistic outputs of ethylene could be found. This design could then be used to compare and contrast actual ethylene values obtained experimentally. Hence the effiency of our E.coli cells could then be calculated. Depending on the effiency value, certain factors and variables could be changed in order to attempt to reach our tinkercell output.

The benefit of using Tinkercell to better understand our system, subsequently also allows us to distinguish the practicality of our project. That is, for example, if low levels of ethylene were predicted to be produced from the model at certain parameters, then efforts into favouring and adapting our system as a plant signalling/communication system could be aimed for in reality under those sorts of conditions. In contrast, if ethylene production was indicated by the model to be high for example, then again, under those certain set of parameters efforts could be re-directed into shaping the objective of the system to be used for plastic production. Hence, by modelling our project using Tinkercell, direction into where the project may lead to in the future can be better defined.

Objectives

-To determine the maximum output of ethylene -To estimate HCN levels and assess potential damage to cell

-Start with a simple model and progress to a more complex one. This allows us to more accurately predict ethylene production

Model 1

Introduction to Model 1

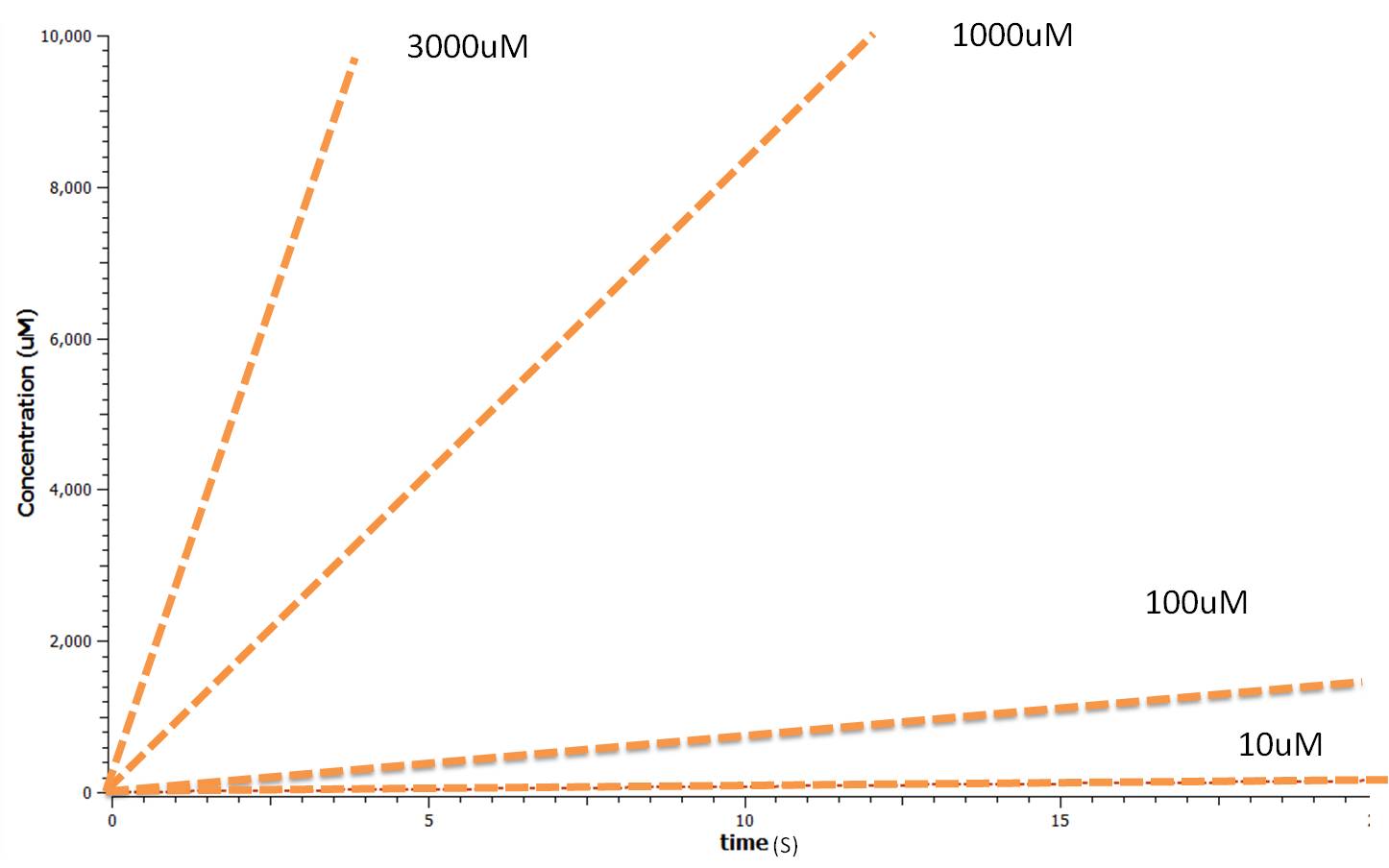

This relatively simple model - as represented in figure 2 - was designed to be the starting point of our kinetic modelling. This uncomplicated system could then be used to obtain an ethylene output. This design comprised only of three enzymes and lacked the transcription and translation stages. The enzymes involved were SAM synthetase, ACC synthase and ACC oxidase - also known as EFE (ethylene forming enzyme). These enzymes were present at fixed concentrations (10, 100, 1000 and 3000 uM) and in a 1:1:1 ratio. Although basic, this model in essence was able to give reasonable output values for ethylene produced. Furthermore with fixed enzyme concentrations the rate at which ethylene is produced depends on the Vmax of the specific enzymes.

This specific rate is defined by the Michaelis-Menton Equation:

kcat*[substrate]*[enzyme]

Rate = -------------------------

km + [substrate]

Assumptions for Model 1

- A 1:1:1 steady state of enzymes.- No product inhibition.

-Substrates (ATP, L-Methionine etc) kept at a constant value due to homeostatic mechanisms in E.coli.

- The best value (km, kcat etc) was always chosen to ensure maximum yield of ethylene.

Parameters and Values used

Met concentration - 150 uMATP concentration - 9600 uM

O2 concentration - 442 uM

SAMsynth Km(Met)- 92 uM

ACCsynth Km(AdoMet/SAM)- 37 uM

EFE Km(ACC)- 12 uM

SAMsynth turnover rate (kcat)- 1.5 per second

ACCsynth turnover rate (kcat)- 18 per second

EFE turnover rate (kcat) - 5.9 per second

Graphs and results

Using Tinkercell a graphical representation of 'Model 1' was generated (Figure 3) using deterministic stimulation. In this figure a graphical representation of the rates - generated internally by Tinkercell's mathematical alogarithms - of ethylene production are shown for each fixed enzyme concentration assumed. As a result not only is production of ethylene shown to be increasing linearly with time, but at a greater rate with increasing concentration of enzyme (SAM synthetase, ACC synthase, EFE) used.

-

Model 2

Model 2 explores the more complicated adaptation of model 1 by incorporating the transcription, translation, and degradation rates of protein and mRNA into the final design. As a result a more realistic model of what would really be happening in the cell leading to ethylene production could be achieved. Of all the sources studied, it was decided that values from the Elowitz repressilator model would be most sensible and relevant to our system. Therefore the degradation, transcription and translation rates were adapted from this model onto ours to factor in fluctuations in concentrations of our three enzymes, as unlike in model 1, enzyme concentration would not realistically be in a 1:1:1 ratio. Therefore using these values, model 2 was able to more realistically follow the metabolic pathway of ethylene production where fluctuations in enzyme concentration were taken into consideration – rather than having them fixed as in model 1.

Elowitz Degradation Values

mRNA degradation rate - 0.00577 mRNA per second Enzyme degradation rate - 0.001155 enzymes per second R0011 PoPs or transcription rate - 0.5 mRNA per second Translation rate -0.117 enzymes per secondGraphs and results

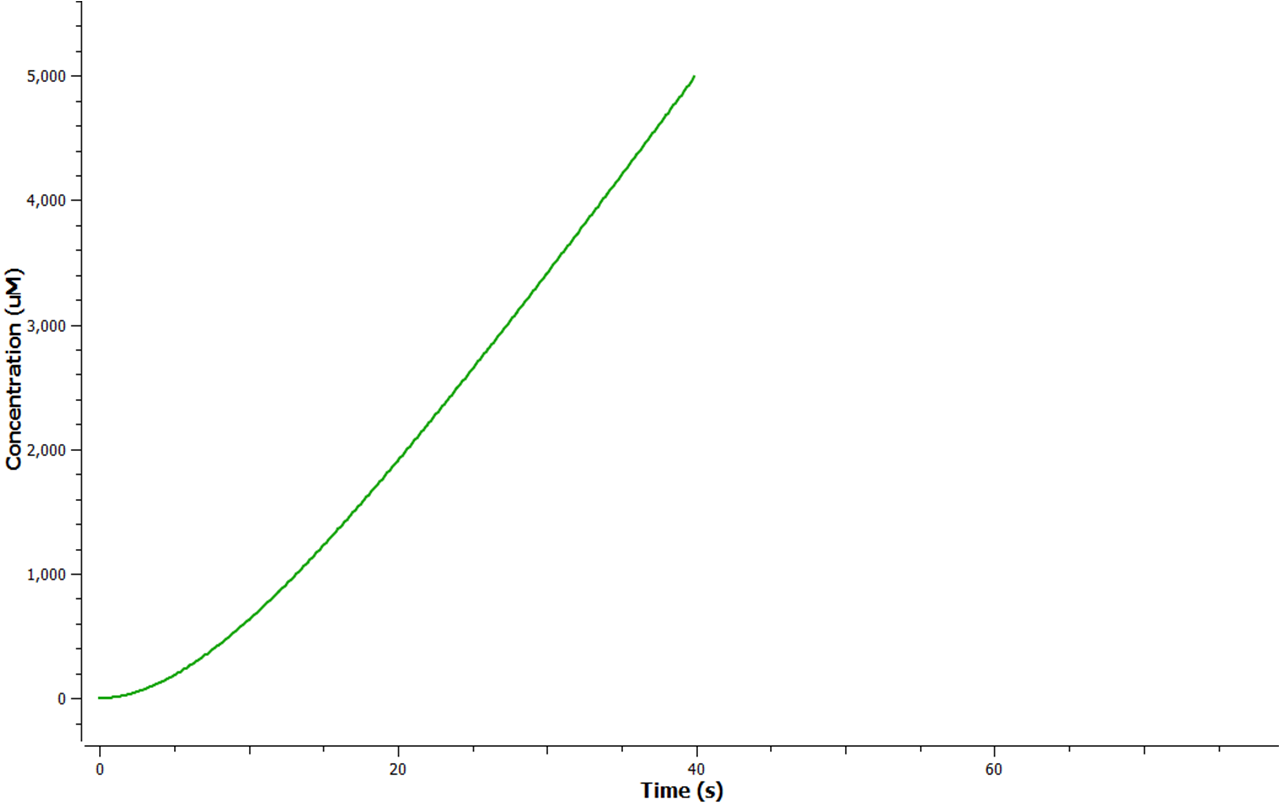

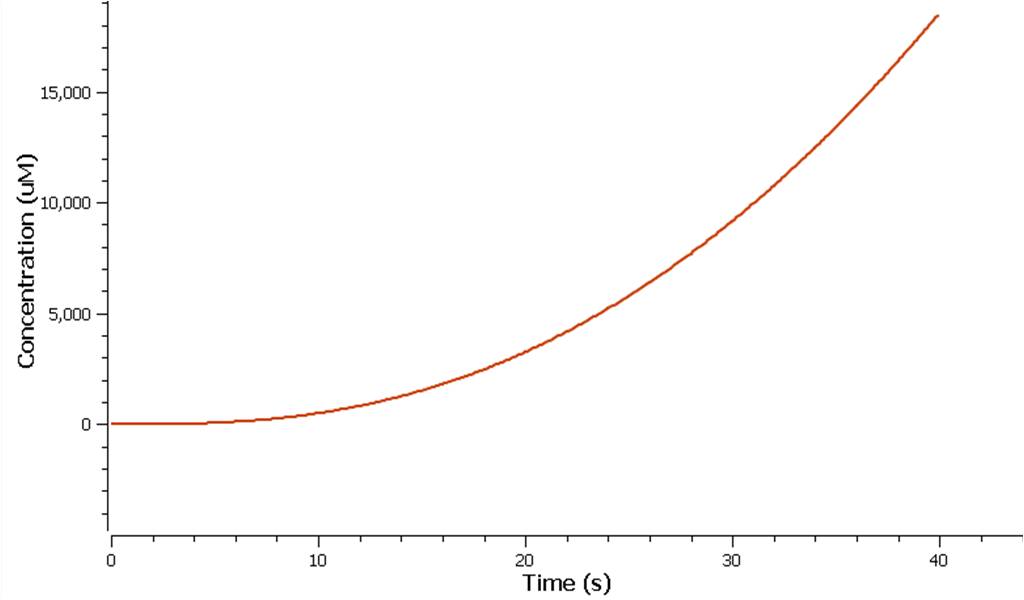

The rate at which mRNA is produced can be seen to start off at a rapid rate. However as time goes on the mRNA can be seen to reach a steady state.

The production of ethylene in this graph looks realitively accurate, however due to the confunding aspects of excess enzyme production, it is unclear if this graph truly represents the total ethylene output. However it can be assumed that the first few seconds accurately portray the ethylene output.

"

"