Team:UTDallas/Project ProjectOverview

| Project Overview | Introduction | References |

|---|

Project Overview

Millions of gallons of toxic petroleum are released into the ocean each year as a result of accidents such as oil spills or natural geological seepage.

Crude oil is a complex mixture of hydrocarbons consisting largely of n-alkane and aromatic hydrocarbons. Saturated hydrocarbons with linear or branched chains comprise the alkane series, which includes paraffinic hydrocarbons. Unsaturated hydrocarbons with benzene rings comprise the aromatic series, which includes the BTEX compounds.

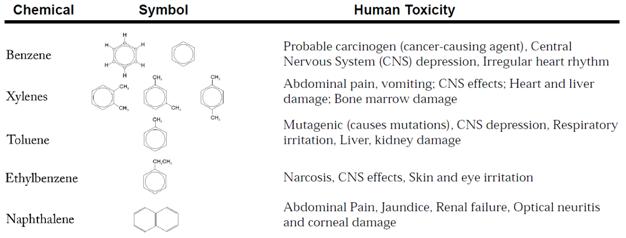

The World Water Assessment Program, the UN’s flagship water protection initiative, describes a host of health risks associated with these chemicals, some of which are enumerated in the table below (adapted from WWAP brochure)

While petroleum constituents are generally found around industry, nitrates are a common ingredient in fertilizers, whose use is widespread in agricultural practice. Nutrient-rich runoff enriches water sources such as lakes, rivers and aquifers with nitrates in a process called eutrophication. This facilitates the onset of algal blooms that deprive the native organisms of oxygen and essential nutrients. Afflicted water sources are difficult and expensive to restore and the process could further harm the wildlife.

Due to stable, unreactive chemical structures, many of the aforementioned chemicals are persistent contaminants that circulate through the environment, thus polluting usable water supplies and marine ecosystems for extended periods of time. In fact, crude residues from the 2002 Prestige spill are still, 8 years later, encountered along Glacian shores. The need to control and mitigate the circulation of such chemicals is therefore both eminent and urgent. To that end, the UT Dallas iGEM team is developing novel, modular biosensors that enable cheap, on-site detection of aromatics, nitrates/nitrites and alkanes in low concentrations using an Escherichia coli chassis.

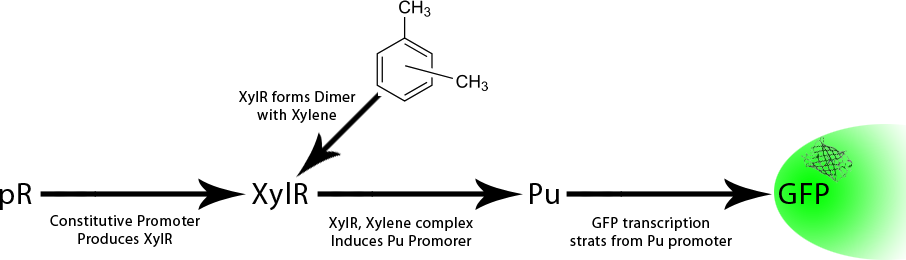

The aromatics sensor builds on the previous work of the Michigan 2009 and Glasgow 2007 teams. Team Glasgow produced a successfully characterized fusion of the pR constitutive promoter and XylR transcription factor of the pu promoter. Team Michigan produced a fusion of the pu promoter and GFP, but failed to characterize the construct. The XylR protein forms a complex with aromatic compounds, which positively regulates the pu promoter. In this way, E. coli co-transformed with these constructs can express GFP and demonstrate sensing capabilities in the presence of aromatics. We successfully characterized the function of the Michigan 2009 construct and demonstrated that it works as expected.

The nitrate/nitrite sensor builds on parts submitted by the Edinburgh 2009 team. This includes a fusion of the nitrate/nitrite-inducible pYeaR promoter and GFP. The pYeaR promoter is positively regulated by the presence of nitrates/nitrites, thus driving the transcription of GFP. This work improves the characterization of these parts by expanding on sensing capabilities using GFP and RFP reporter systems and induction by a variety of nitrate/nitrite compounds.

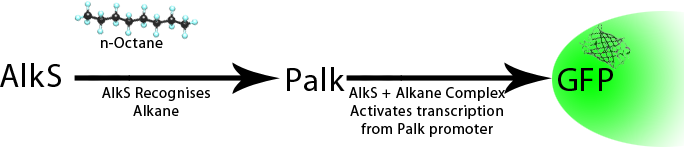

The alkane sensor includes components of the alkane metabolic pathway of Pseudomonas putida OCT. The promoter region pAlkB drives the transcription of the alk gene cluster. AlkS, its transcription factor, is encoded by the alkS gene. We ordered oligonucleotides from Sigma-Aldrich containing the appropriate sticky ends for the fusion of pAlkB to a fluorescent protein part to form a reporter construct. A plasmid containing alkS was kindly provided by Dr. Jan Roelof van der Meer of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, who helped pioneer luminescent whole-cell biosensors. AlkS binds to n-alkanes to form a complex that positively regulates the pAlkB promoter to drive the expression of fluorescent protein. The two plasmids containing the promoter/fluorescent protein fusion and the AlkS transcription factor were to be co-transformed into DH5a to characterize sensing capabilities. Unfortunately, we were unable to realize the alkane sensor component due to issues with the ligation of the ordered oligonucleotides to the iGEM backbone. We tried various other approaches including ligation after dephosphorylation of the vector and phosphorylation of the insert as well as blunt-end ligations. After a number of trials, pAlkB failed to properly ligate onto the iGEM backbone. We assess that this was due to compatible sticky ends that caused it to repeatedly self-ligate.

"

"