Team:Heidelberg/Project/Mouse Infection

From 2010.igem.org

in vivo studyAbstractGene therapy offers a great tool for treatment of various human diseases and has shown tremendous promise and success in many recent clinical trials. Nevertheless, two most critical hurdles that remain are 1) the development of delivery vectors that allow for the highly cell- and tissue-specific expression of a gene of interest (GOI), as well as 2) the implementation of novel systems that permit the tightly controlled and fine-tuned expression of this gene in human patients. To fill in these two essential gaps, the iGEM Team 2010 of Heidelberg is introducing molecular evolution of viral gene transfer vectors as well as mi(cro)RNA-based gene regulation technology into the realm of synthetic biology. By combining these two powerful new methodologies, we have succeeded in engineering synthetic viral miRNA vectors that we could demonstrate to provide potent, specific and regulated gene expression in cultured mouse and human hepatocytes. Most importantly, we also document the successful use of our novel approach to achieve tightly controlled and liver-specific expression of a vector-encoded recombinant DNA in intact livers of adult mice. Our work and data thus pave the way for the future further expansion and utilization of our unique miRNA/vector kits in numerous biotechnological and especially biomedical applications. IntroductionGene therapy offers a fantastic and unique tool for efficient treatment of various human diseases with a genetic cause, ranging from metabolic disorders and cancers to infections with different viral pathogens (Zincarelli, Soltys et al. 2008). In principal, the underlying concept comprises the initial identification of a certain genetic defect, such as a deletion of a critical tumor suppressor gene which then causes cancer, or a mutation in a gene that is essential for a given metabolic pathway and whose loss or malfunction accordingly triggers symptoms of a disease. Once identified, gene therapists then attempt to correct this specific defect by introducing a correct copy of the missing or mutated gene back into the affected cell, hoping that this newly delivered gene will behave just like the original that it replaces. For transfer of this therapeutic gene sequence, one can choose between physical carriers, such as liposomes or nanoparticles, or alternatively, many groups engineer naturally occurring viruses, such as Adenoviruses, Lentiviruses or Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) as gene delivery vehicles. The latter hold the particular advantage that viruses have evolved to potently and, at least in many cases, specifically transfer their genetic cargo to cells, implying that a recombinant therapeutic DNA (or RNA) replacing these genes will behave just the same. However, as one can easily imagine from the complexity of gene expression networks in all cells, especially in those of higher organisms, this whole process of transferring a foreign gene into a cell and expressing it there is everything but trivial, and success is not necessarily guaranteed. In essence, there are several main challenges that still need to be overcome before gene therapy, or more generally gene transfer, in humans can become a routine application, namely, improvements in 1) specificity, 2) potency, 3) control and 4) related to all this, safety. Unsurprisingly, there have been a plethora of attempts in the past to tackle these challenges, and a great deal of success has been reported in the literature. What is curious about these findings and advances, however, is that the vast majority of them have merely focused on the recombinant DNA template itself and have tried to (and often managed to) improve its particular properties, such as stability or encapsidation into the shell of a recombinant virus for delivery to the target cell. Still, these particular approaches to improve the therapeutic DNA have taught us an important lesson, namely, that for successful, specific and potent gene transfer into human cells, especially into human patients, DNA is not enough ! Instead, there are two additional levels that are at least equally important and that have therefore been in the center of our team's focus: 1) the carrier used for gene delivery and 2) the control of gene expression inside the cell. More specifically, we have decided to study and improve the above already mentioned Adeno-associated virus (a large family of over 100 naturally occurring different serotypes) as a gene delivery vehicle due to a number of outstanding advantages of this particular virus for use in cell and tissue engineering, including the complete lack of pathogenicity of the parental wildtype viruses plus their capability to infect a wide range of target cells and tissues (Grimm, 2002). On the other hand, this broad tropism can also be a disadvantage in cases where one would like to target a very specific cell type and concurrently avoid off-target gene expression elsewhere in the body. Therefore, several research groups (including the one of our instructor Dr. Grimm) have very recently begun to devise novel methods to molecularly engineer synthetic "designer" AAVs based on naturally occurring capsids which ideally combine and enhance their best properties. For instance, it is now possible to create entire libraries of AAV capsids by inserting short targeting peptides into exposed regions of the virus surface, or alternatively, by randomly point mutating single amino acids in the capsid proteins. The latest and most potent approach is, however, to shuffle entire capsid genes by first fragmenting and subsequently re-assembling the parts into hybrid particles. Ideally, the resulting chimeras will combine the assets of all parental viruses, such as high potency in a given cell type coupled with evasion of neutralization by human anti-AAV antibodies (Grimm et al., 2008). Regarding the second critical level, regulation of gene expression following DNA delivery, it would be particularly crucial in the context of many gene transfer/therapy applications to be able to fine-regulate the level of the resulting protein expression, considering that uncontrolled over-production of certain proteins can be highly toxic or even lethal to cells and tissues. Unfortunately, as mentioned above, most approaches in this direction thus far have mainly focused on the DNA itself and accordingly mostly dealt with the development of improved promoter sequences that mediate controlled gene expression under certain conditions. What has been largely ignored until very recently, however, is the fact that gene expression can also be regulated on the RNA level, namely, via RNAi technologies. In this respect, we reasoned that the novel and broadly applicable miRNA tools engineered by our iGEM team should prove extremely useful in combination with gene therapy vectors, considering that they have been devised to permit very tight control over the expression of a given gene on the RNA level (by controlling translation and/or mRNA stability, which is the natural mechanism of miRNA action). Specifically, we wanted to explore the feasibility to fuse a gene of interest (GOI) with binding sites for either a naturally occurring miRNA or for a synthetic miRNA that is co-expressed from a second "tuning" vector. In either case, the binding site can then be designed to match the mi/shRNA either perfectly, which will result in nearly complete knockdown of gene expression, or it can be imperfect, which will yield a more subtle reduction in gene expression (for details, see our synthetic miRNA kit). Accordingly, we utilized our various novel tools to establish an entirely new system for fine-regulated gene expression from viral gene therapy vectors, in which control is exerted no longer on the DNA level, but in addition also on the steps of 1) gene delivery and 2) fine-tuning. Most importantly, as with any novel system for regulated gene expression, there is no guarantee that results obtained in cultured cells are relevant for, and will straight-forwardly translate into, identical finding in living animals or ultimately human patients. Therefore, we reasoned that it would be mandatory following the design and in vitro validation of our novel constructs to also assay and ideally confirm their functionality in living organisms in vivo, i.e., in adult mice.

In the following, we will summarize our results from the in vivo evaluation of the two main strategies outlined above in the livers of adult mice and will demonstrate how modifying the viral gene vehicle capsid can drastically affect the specificity and level of gene expression in cultured cells versus living animals, and how engineering a given gene expression cassette by adding perfect or imperfect mi/shRNA binding sites can further fine-tune the strength of gene/protein expression at will.

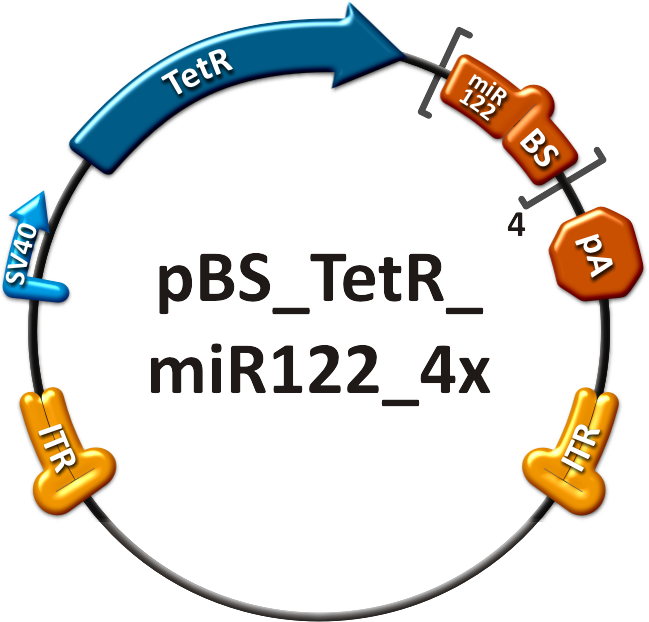

ResultsStrategiesAs outlined, we have pursued two fundamentally different strategies to achieve regulated gene expression in mice, which are control via the viral capsid as well as via RNAi/miRNAs. Generally, to measure the success of each individual strategy, it was mandatory to be able to detect and quantify gene expression in living adult mice to begin with. Moreover, we had to define a standard based on which we would evaluate the specificity and efficiency of each new construct and strategy that we wanted to test. As we were going to target the liver of mice (since it is one of the most therapeutically relevant organs plus concurrently very susceptible to gene transfer), we decided to use the particular AAV serotype 8 (AAV8) as our standard, based on previous findings by Dr. Grimm and others that it mediates maximum transduction of livers in adult mice. Additionally, we picked Firefly luciferase as our reporter gene as it can be easily detected and quantified in living mice following a simple intraperitoneal injection of luciferin substrate and using a sensitive camera system. Hence, in our very first animal experiment, we infused adult white mice with an AAV8 vector expressing Firefly luciferase from the universally active SV40 promoter and then measured luciferase levels in the liver 5 days after injection. As shown in the center of Figure 1, we were indeed able to detect a very strong expression in all livers of three independent mice, with an average photon count of 2.77x108 per mouse. In all subsequent experiments, this value served as our reference based on which we aimed to achieve a fine-regulation of in vivo gene expression. 1. Viral capsid / Gene deliveryNext, we asked how delivering the exact same luciferase vector to mice from a different viral capsid would alter the expression levels in the liver. For this purpose, we used our lead candidate from the virus shuffling and selection procedure described in the homology based capsid shuffling section. As noted there, this one particular capsid was curious in that it was the only one capable of potently transducing Huh7 and HepG2 cells, strongly suggesting that it might also yield reasonable gene expression in vivo. Indeed, when we performed the experiment with this synthetic capsid under the exact same conditions as with our standard AAV8 capsid, we again noted effective luciferase gene expression in the livers of three independently injected mice. 2. miRNA-based OFF targetingIn the above described first set of experiments, we aimed to fine-regulate gene expression by modifying the viral capsids delivering the same gene as was originally expressed from our standard AAV8 vector. In the next step, we asked whether it was also possible to exploit the endogenous expression of cellular miRNAs in order to further control gene expression levels from a viral vector. Generally, this strategy can be exploited in at least two ways: 1) a GOI can be fused with a perfectly matching binding site for such a miRNA, which will typically result in nearly complete inhibition of gene expression, or 2) this site can be imperfect which will yield a gradual reduction of expression. This obviously validated our hypothesis that cellular miRNAs can be exploited to substantially regulate the expression of a vector-encoded recombinant DNA and is thus further proof for our concept that neither DNA nor the vector are sufficient to achieve the maximum possible level of control over in vivo gene expression.

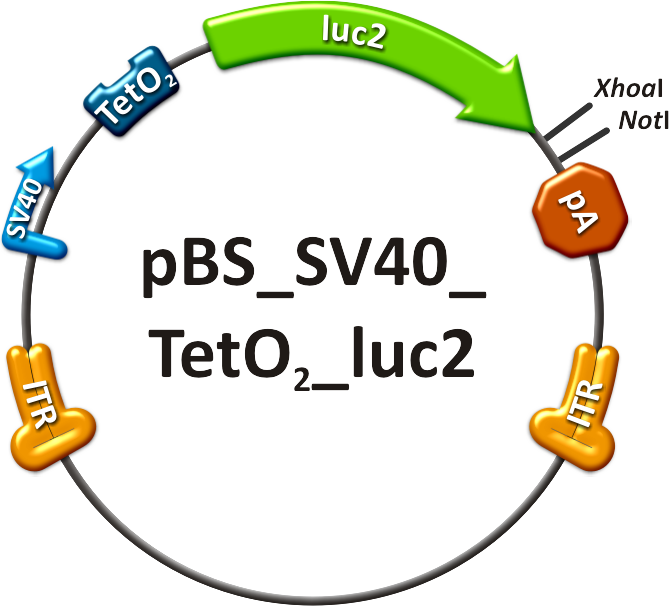

3. miRNA-based fine-tuningAs just indicated, we predicted that fusing our luciferase gene with an imperfect binding site for a miRNA would result in a more gradual reduction in gene expression as compared to the perfect site. To test this hypothesis, we generated a series of expression vectors in which the luciferase gene was tagged with perfect or imperfect binding sites for an artificial miRNA (an shRNA directed against the hAAT gene). This miRNA was then packaged into and co-expressed from a second AAV8 vector that we generated in parallel. The results we obtained are shown in Figure1. Three important conclusions can be drawn from this experiment: Bioluminescence imaging

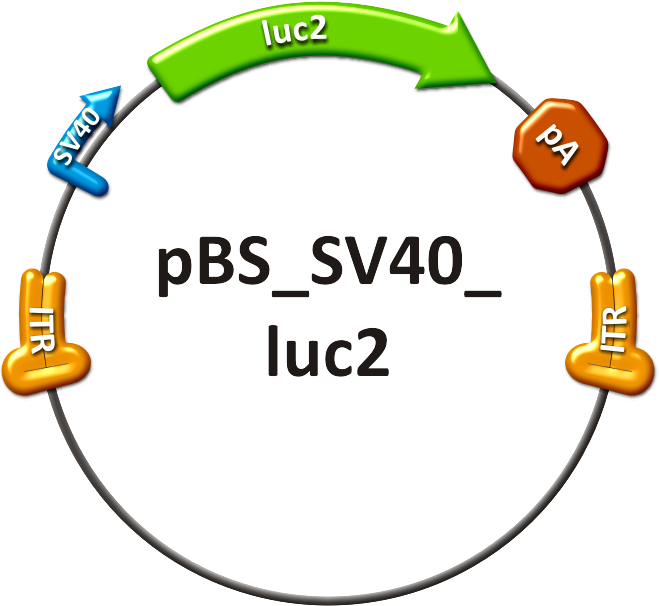

Figure 1: Scheme of luciferase DiscussionIn the above described and documented set of animal experiments, our team has been the very first within the iGEM competition to demonstrate the enormous power and promise of viral vector evolution and miRNA technologies to achieve a level of fine-regulation of in vivo gene expression that has previously been unprecedented. Most importantly, it must be pointed out that we consider our data just as a tip of the iceberg and as a highly promising starting point for numerous further similar developments and improvements that we expect in the future of synthetic biology and biomedicine. MethodsContructsThe in vivo analysis should enlighten our gene therapy approach using AAV tropism as well as miRNA binding sites as trigger for expression. The following constructs have been subcloned separately into the AAV context to accomplish those tasks:

Production of recombinant virusThe viruses were produced in HEK 293-T cells and purified on an iodixanol gradient according to the virus production protocol. Before infection, the titer of the viruses was quantified using quantitative realtime PCR. Procedure involving animalsThe mouse experiments were conducted in accordance with the animal facility of the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg. Female NMRI mice were obtained from a collaboration with Dr. Oliver Müller. At 8-10 weeks of age, the animals were injected in the tail vein (TV), with ~ 1x1011 particles of AAV-SV40-luciferase in 200µl of 1x phosphate-buffered saline. The mice are transferred to a holding device which restrains the mouse while allowing access to the tail vein. The tails were warmed before the injections and injections were carried out using 27 gauge needles. All the mice recoverd from the injection quickly without loss of mobility or interruption of grooming activity [http://2010.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project/Mouse_Infection#References (Zincarelli et al., 2008)]. in vivo animal imagingMice were anesthesized in an isofluran chamber. The mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200µl of a 30 mg/ml concentration of D-luciferin. This injection starts the luminescence of luc2. Mice were measured for one to seven minutes post injection under the in vivo bioluminometer. ReferencesGrimm, D. (2002). "Production methods for gene transfer vectors based on adeno-associated virus serotypes." Methods 28(2): 146-157.

|

|||

"

"