Team:Alberta/modelling

From 2010.igem.org

(→Characterizing the assembly process) |

|||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

*Secondly, AB bytes can ligate only to BA bytes, while BA bytes can ligate only to AB bytes. | *Secondly, AB bytes can ligate only to BA bytes, while BA bytes can ligate only to AB bytes. | ||

| - | Considering these points, we see that during the creation of an 8-byte construct, there will be some intermediate sized constructs that will be visible on a gel | + | Considering these points, we see that during the creation of an 8-byte construct, there will be some intermediate sized constructs that will be visible on a gel. With some thought on the second point, we see that intermediate constructs can be made up of multiple arrangements of bytes. |

For instance, during the creation of an 8-byte construct, a medium sized 4-byte construct will be made up of the following combinations of bytes: | For instance, during the creation of an 8-byte construct, a medium sized 4-byte construct will be made up of the following combinations of bytes: | ||

Revision as of 18:31, 26 October 2010

Goal of the model

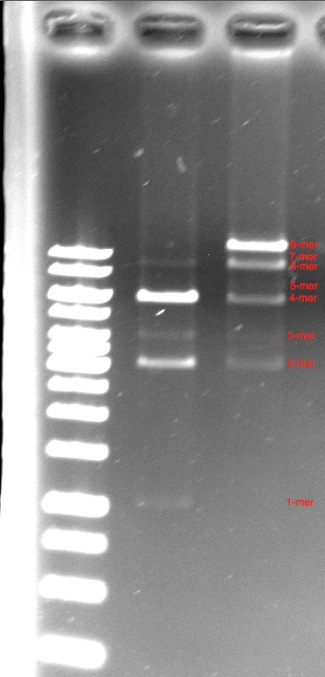

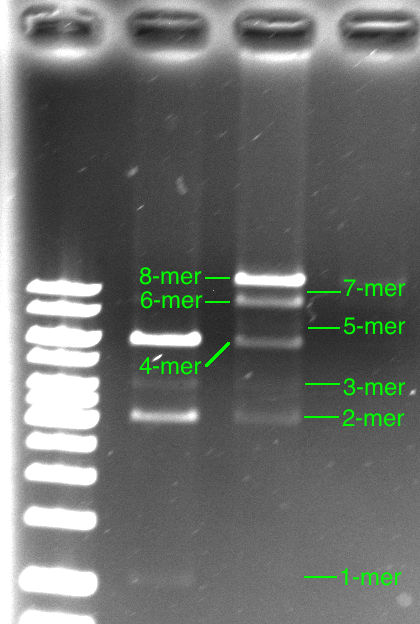

After the assembly process, the construct can be run on a gel. Multiple bands appear. The top band contains the full construct while all of the bands below contain failed intermediate constructs of lower length.

Why do the band’s intensities alternate in intensity like that? How can the byte addition efficiency be calculated from the gel?

To answer these questions, we must consider the assembly process of a construct. If we follow through the assembly process while considering the efficiency k of byte addition at each step, the expected relative intensities of the bands in the gel can be calculated.

Characterizing the assembly process

For this model, there are a few points to consider that characterize the assembly process:

- First, byte addition occurs with a constant efficiency k, which is the same for AB byte additions and BA byte additions. This means that for a given byte addition, a fraction k of the existing construct is successful in growing in construct size, while (1-k) remains at the same construct size because of no ligation.

- Secondly, AB bytes can ligate only to BA bytes, while BA bytes can ligate only to AB bytes.

Considering these points, we see that during the creation of an 8-byte construct, there will be some intermediate sized constructs that will be visible on a gel. With some thought on the second point, we see that intermediate constructs can be made up of multiple arrangements of bytes.

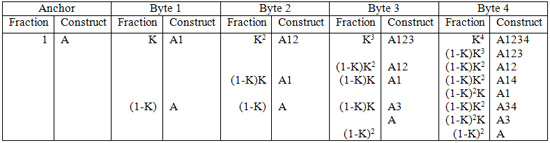

For instance, during the creation of an 8-byte construct, a medium sized 4-byte construct will be made up of the following combinations of bytes:

- 1,2,3,4

- 1,2,3,6

- 1,2,3,8

- 1,2,5,6

- 1,2,5,8

- 1,2,7,8

- 1,4,5,6

- 1,4,5,8

- 1,4,7,8

- 1,6,7,8

- 3,4,5,6

- 3,4,5,8

- 3,4,7,8

- 3,6,7,8

- 5,6,7,8

Note that if all even numbered bytes are of equal length and if all odd numbered bytes are of equal length, then all of the aforementioned 4-byte constructs are all of the same length. This means that their corresponding bands on a gel would all be superimposed into one band on the gel.

This occurs for all the intermediate sized (failed) constructs. This concept is important for the derivation of a general set of equations describing the expected relative band intensities for each band in a post-assembly gel.

Creating the model

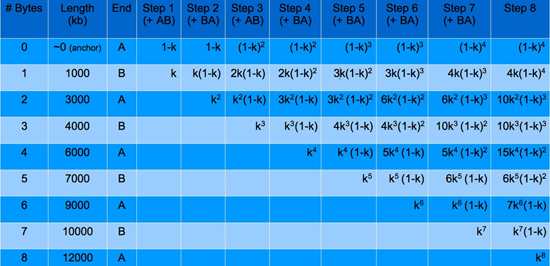

Now imagine the construction process of an 8-byte construct. We’ll call it the octomer. It will be made up of alternating 1kb AB bytes and 2kb BA bytes. We’ll follow the construction of it while keeping track of what fraction of all of the intermediate constructs ends up at particular sizes (as a function of the ligation efficiency k).

First, the anchor is added to the bead. We’ll say that 100% (k=1) of the construct is at anchor length at this point. Then, byte 1 is added to the anchor with efficiency k.Now, k of the constructs are made up of anchor and byte 1, while (1-k) is left as anchor. Adding byte 2, we see that k2 of the constructs are made up of anchor, byte 1 and byte 2, while (1-k)k are left as anchor plus byte 1, and while (1-k) is still left as just anchor. It is still (1-k) because byte 2 could not ligate to the anchor at all (because the ends are not compatible). It becomes more complicated for higher byte additions. This process can be mapped and placed in the following table.

Each column represents the addition of a byte. The “Fraction” column describes the fraction of the corresponding construct in the “Construct” column. “A” refers to anchor, and the numbers beside it refer to the bytes attached to the anchor. For instance, A34 refers to the construct made up of the anchor, byte 3 and byte 4.

The table can be continued indefinitely (up to byte 8 in this example).

The key thing to keep in mind when creating this table is that whenever there is a byte addition, k constructs are successful, and (1-k) are not, and this can only happen for bytes with the appropriate sticky ends.

Now assuming that all even numbered bytes are of equal length and that all odd numbered bytes are of equal length, these fractions can be combined. For instance, in the “Byte 4” column, since A12, A14, and A34 are of the same length and would therefore superimpose on a gel, these fractions can be summed together resulting in the total fraction of constructs at the 2-byte construct length. This can be done for each construct size in the “Byte 4” column and repeated for every other “Byte #” column. The results of doing this are shown below in the following table for up to step 8 – where the 8th byte is added.

From the table, we can see that the k exponents and the (1-k) exponents are easily predictable as the steps continue. The coefficients are not, but it can be shown that the coefficients for the equations in Step n correspond to row n of a special kind of Pascal’s triangle. They follow the integer sequence of [http://www.research.att.com/~njas/sequences/A065941 A065941 from the Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences], which can be created with the following Matlab code:

g=1; nBytes=8;

for n=1:nBytes

for k=1:g

Triangle(n,k)=nchoosek(n-1-floor((k)/2),floor((k-1)/2));

end

g=g+1;

end

where nBytes is the number of bytes the construct is made up of (including the anchor for this code). For a construct of length n, only the nth column is needed.

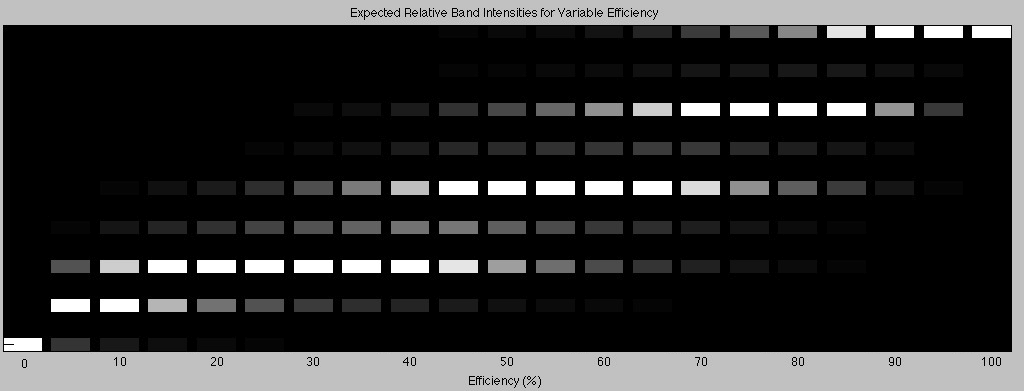

Back to our octomer. Now that construction is complete and now that we have our handy table, we know the theoretical proportions of construct at each length. For our octomer assembly process, the brightness of each band can be predicted with the set of equations in the “Step 8” column and multiplying with the corresponding length. This was done for k values ranging from 0 all the way up to 1 in steps of 0.05. When exposing a gel, usually the brightness is adjusted so that the bands are within a visible range. In the model, the results of each equation evaluated at a given k were normalized to the largest value. This is analogous to adjusting the exposure time of your gel such that the brightest band just about saturates the pixels in the output image. The results were output to an image. Each column is the set of equations (in the “Step 8” column) evaluated at a specific k value, multiplied by the corresponding length, and normalized to the brightest band.

Each lane represents the construction of the 8-byte octomer at a different ligation efficiency. Each row represents the construct length. The top row represents the 8-byte construct, the next row is the 7-byte construct and so on. At 0% efficiency, the only DNA left after construction is anchor so it is the only band seen on a gel after the assembly process. At 100% efficiency, all of the dna has ligated perfectly and every construct is exactly 8 bytes long. This results in only one band at the corresponding octomer length. For the intermediate efficiencies, we see a variety of band patterns. For the higher efficiencies, we see the same alternating brightness in the band pattern that was seen in our actual construction of the octomer in the lab.

How efficient was our construction of the octomer?

So how efficient was our construction of the octomer in the laboratory? From the model, and the figure above, we can tell easily that the efficiency k is above 85% since our 8-byte construct band was the brightest band.

Looking closely at our octomer gel, we can say that the band for the 8-bye construct is at least three times brighter than the band for the 6-byte construct. Since the octomer gel appears to have been over exposed (and saturated the pixels), it is hard to tell, but 3 times seems to be a good estimate. Keeping this in mind and looking at the matlab output for finer efficiency simulations, we can see that this corresponds to a byte addition efficiency of at least 94.5%.

The matlab code

% This program will take in the lengths of each of your bytes and output

% the relative intensities of the bands expected.

function [Intensities] = findIntensities(nBytes,AnchorLength,OddByteLengths,EvenByteLengths)

% The anchor counts as a byte in this code. So for octomer, nBytes == 9.

x = 1 ;

% Create the proportion coefficients

for g=1:nBytes

cT(g,1) = nchoosek(nBytes-1-floor((g)/2),floor((g-1)/2)) ;

end

% Create the (1-K) exponents

b = 0.5:0.5:nBytes/2 ;

exps1_k = floor(b)'; % The (1-k) exponents

% Create the K exponents

kExps = (nBytes-1:-1:0)' ; % The k exponents

% Create the length coefficients

cL(1:nBytes,1) = EvenByteLengths ;

cL(1,1) = AnchorLength ;

cL(2:2:nBytes,1) = OddByteLengths ;

for h=2:length(cL)

cL(h) = cL(h) + cL(h-1) ;

end

cL = flipud(cL)

cT

% Compute the intensities for each length (leaving k as a variable)

syms k ;

for R=1:nBytes

IntenSym(R,1) = cT(R)*((1-k)^exps1_k(R))*(k^kExps(R))*cL(R) ;

end

IntenSym

% Compute the intensities at various values of k. Also normalize

% intensities to the brightest band (per lane)

for k = 0 : 0.05 : 1 % Being evaluated at every 5% efficiency

IntensEval(:,x)=eval(IntenSym) ; % Evaluate

Intensities(:,x)=IntensEval(:,x)/max(IntensEval(:,x)) ; % Normalize

x = x + 1 ;

end

% Now create a picture

w = 0 ; p = 0 ; t = 3 ;

for a=1:length(Intensities(1,:))

for b = 1 : length(Intensities(:,a)) % cycles through rows in the a'th column

Pic(b+w,a+p:a+p+t) = Intensities(b,a);

w = w + 2 ;

end

w = 0 ; p = p + 1 + t ;

end

set(gcf, 'Position', [0 0 1300 400]) % Stretch image so bands look rectangular like a real gel

colormap(gray); imagesc(Pic)

title('Expected Relative Band Intensities for Variable Efficiency')

xlabel('Efficiency (%)')

For the octomer built in the lab, the anchor was 56 base pairs long, the odd numbered bytes were 976 base pairs long, and the even numbered bytes were 2083 bytes long. To run the code for the expected bands for this octomer, the following code must be typed into the command window:

findIntensities(9,56,976,2083)

"

"