Team:Imperial College London/Chassis

From 2010.igem.org

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

<li>A peptide display system combined with | <li>A peptide display system combined with | ||

<li>A quorum sensing system activated by a linear AIP. | <li>A quorum sensing system activated by a linear AIP. | ||

| - | <li> | + | <li>A portable chassis </li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</td> | </td> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:58, 28 October 2010

| Chassis & Vectors |

| This page is an overview of our chassis B. subtilis, why we chose it, and its key points. We also discuss the vectors used. |

| Chassis | ||||

|

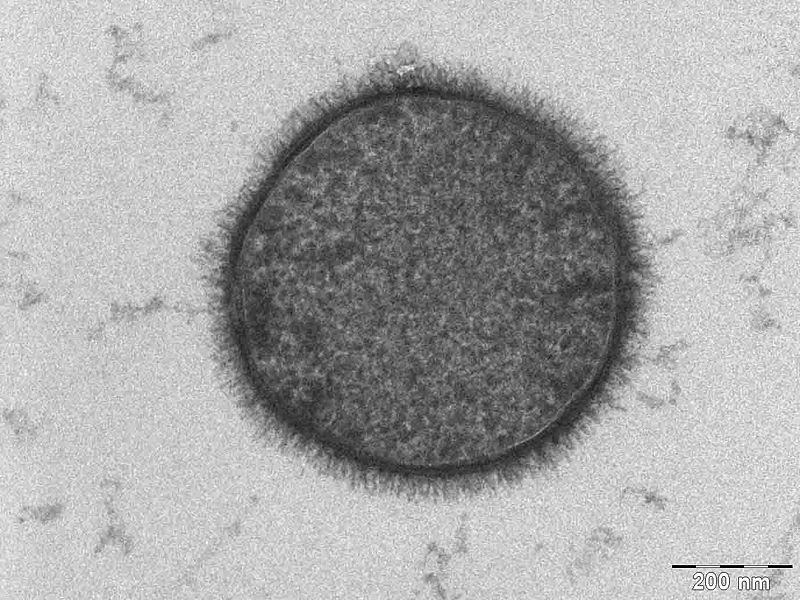

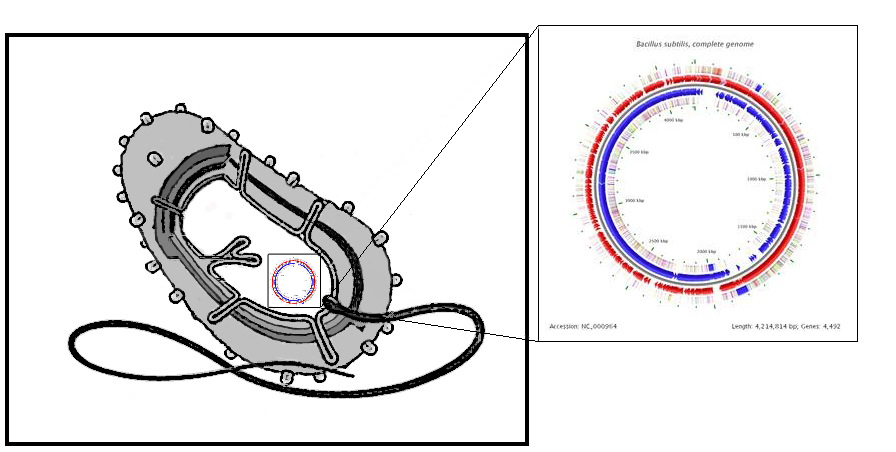

We selected B. subtilis because it is a well characterized gram positive bacterium that is non pathogenic. It was convenient but also a coincidence that within our chosen chassis were features with which we could manipulate to use in our detection module. Below is a brief table summary of how B. subtilis meets our system requirements and also some of the issues we encountered throughout the implementation process and how we overcame them. | ||||

| Bacillus subtilis Breakdown | ||||

| ||||

| Notes:

Bacillus uniquely utilizes a quorum sensing system based on using small peptides as autoinducers. Many other bacteria including gram negative bacteria use a QSS based on circular or post-translationally modified peptide display systems; this introduced problems with our desire to re-engineer the small peptide fragment. Bacillus however presents linear peptides on its cell wall. Small autoinducing peptides of a downstream signaling system could be released by the cleavage of these membrane-anchored cell surface proteins. This involves including a protease cleavage site between the membrane anchored domain and the autoinducing peptide. Proteases released from the Cercaria parasite would target this site and hence we can detect them as our system becomes activated. Protease detector peptides (small linear quorum sensing peptide attached to protease recognition sequence) may also get trapped between the cell wall and cell membrane. To avoid this we looked into mechanisms of transport and attachment of these peptides to the outside of cell wall. An alternative was to secrete detector peptides into the medium as B. subtilis is very good at secreting proteins. The LytC cell wall delivery and anchoring system was chosen to satisfy our system of peptide presentation. Specifically, our protease cleavage site linker peptide plus autoinducing peptide were attached to the cell wall binding domain of an endogenous (to Bacillus) LytC surface protein. N.B. An additional option considered was to attach the small protease detector peptides on to pili (fimbriae) that are normally presented on the bacterial cell. This has been done routinely on E.coli fimbriae at non-conserved regions and outer membrane proteins to present various antigens 1. There is also a good review of a variety of export patways that have been used 2 in gram negative bacteria. There is a lot work done on gram positive bacteria, although there is a detailed and very accessible review 3 of current understanding of G+ve cell surface. | ||||

| ||||

| Safety | ||||

| ||||

| Notes:

Bacillus is a naturally occurring soil bacterium that presents no pathogenicity to humans. We aim to introduce our new DNA into existing essential genes. The disruption of these genes renders the bacteria unlikely to exist outside of the lab or eventual product environment. | ||||

| Design Considerations | ||||

|

| ||||

| Notes:

Fortunately, B. subtilis was the chassis of choice of the IC iGEM 2008 team. This means that there are now Bacillus-friendly parts in the registry that we can use and also further characterize and contribute towards. | ||||

|

| ||||

| Vectors |

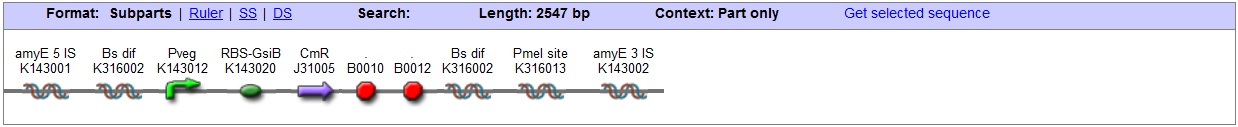

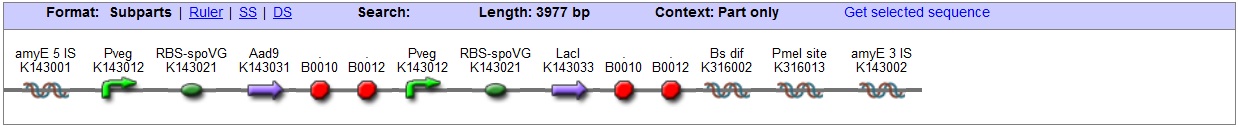

| Working with B. subtilis we were able to implement three additional safety mechanism in our design by creating three novel transformation vectors: The <bbpart>BBa_K316027</bbpart> and <bbpart>BBa_K316022</bbpart> target the AmyE and <bbpart>BBa_K316020</bbpart> the PyrD genomic loci, thereby disrupting vitally important genes for starch catabolism and uracil synthesis respectively. The cells will thus depend on appropriately supplemented medium and will be unable to survive outside of a controlled environment. Additionally in all the vectors the antibiotic-resistance markers are flanked by Dif-sites which allow excision of the marker sites after successful usage. The <bbpart>BBa_K316027</bbpart> vector targeting the AmyE locus also contains LacI which allows for Hyper-spank controlled testing constructs to be characterized: |

| AmyE vector |

|

<bbpart>BBa_K316022</bbpart> AmyE locus This vector has been designed using the amyE 5' <bbpart>BBa_K143008</bbpart> and 3' <bbpart>BBa_K143009</bbpart> integration sequences for integration into B. subtilis genome. Insertion into the amyE locus provides a selection marker as the bacterium will no longer be able to breakdown starch. An iodine assay can be used to confirm integration. This phenotype makes the transformed bacterium considerably less likely to survive in natural environments. Chloramphenicol Resistance This vector also contains a positive selection marker, flanked by two dif sites. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase <bbpart>BBa_J31005</bbpart> provides resistance to chloramphenicol antibiotic. Dif <bbpart>BBa_K316002</bbpart> sites allow excision of the antibiotic marker after integration, thus allowing the same marker to be used again or as a precaution against horizontal gene transfer. Blunt end cloning site PmeI restriction site <bbpart>BBa_K316013</bbpart> is designed as a cloning site. Due to the 8bp recognition sequence it is a rare site that can be used to cut the vector only once. Features |

| AmyE-LacI vector |

|

<bbpart>BBa_K316027</bbpart> AmyE locus This vector has been designed using the amyE 5' <bbpart>BBa_K143008</bbpart> and 3 <bbpart>BBa_K143009</bbpart>' integration sequences for integration into B. subtilis genome. Insertion into the amyE locus provides a selection marker as the bacterium will no longer be able to breakdown starch. An iodine assay can be used to confirm integration. This phenotype makes the transformed bacterium considerably less likely to survive in natural environments.

Chloramphenicol Resistance This vector also contains a positive selection marker, flanked by two dif sites. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase <bbpart>BBa_J31005</bbpart> provides resistance to chloramphenicol antibiotic. Blunt end cloning site PmeI restriction site <bbpart>BBa_K316013</bbpart> is designed as a cloning site. Due to the 8bp recognition sequence it is a rare site that can be used to cut the vector only once. Features |

| PyrD Vector |

|

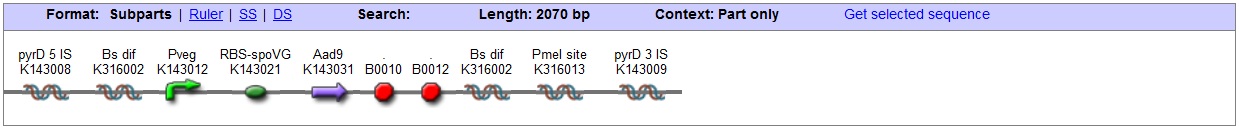

<bbpart>BBa_K316020</bbpart> PyrD locus This vector has been designed using the Pyrd 5' <bbpart>BBa_K143001</bbpart> and 3 <bbpart>BBa_K143002</bbpart>' integration sequences for integration into B. subtilis genome. Insertion into the pyrD locus provides a negative selection marker as the bacterium will no longer be able to synthesise uracil. Thus medium supplement of 40ug/ml is required for growth. This phenotype makes the transformed bacterium considerably less likely to survive in natural environments. Spectinomycin Resistance This vector also contains a positive selection marker, flanked by two dif sites. Aad9 <bbpart>BBa_K143065</bbpart> provides resistance to spectinomycin antibiotic. Dif sites <bbpart>BBa_K316002</bbpart> allow excision of the antibiotic marker after integration, thus allowing the same marker to be used again or as a precaution against horizontal gene transfer. Blunt end cloning site PmeI restriction site <bbpart>BBa_K316013</bbpart> is designed as a cloning site. Due to the 8bp recognition sequence it is a rare site that can be used to cut the vector only once. Features |

| Dif-site excision in B. subtilis |

|

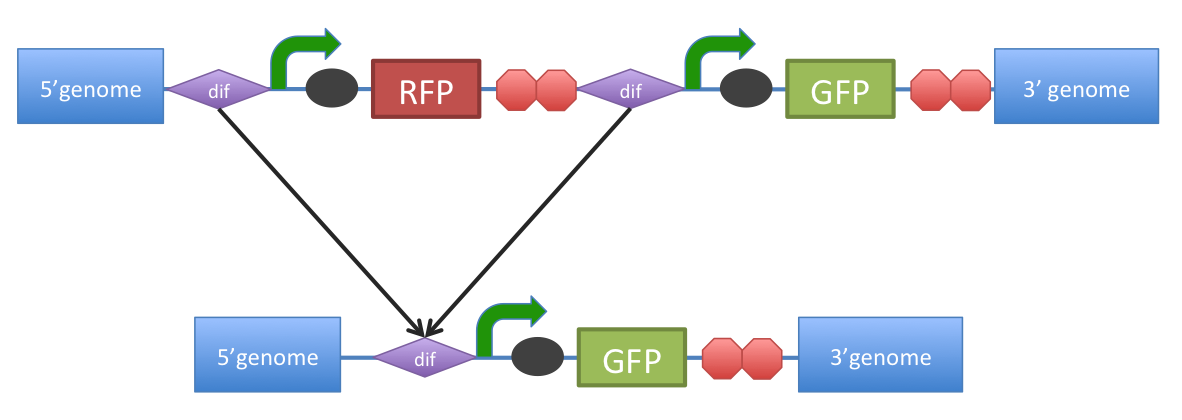

B. subtilis dif: sequence-specific recombinase recognition site In cells with circular chromosomes, recombinatorial repair and homologous recombination can generate multimeric chromosomes 1. Dif sites are part of a system to ensure that multimeric chromosomes can be separated to monomers, which is required for proper sharing of genetic material between daughter cells. In B. subtilis the tyrosine family recombinases such as RipX and CodV mediate the separation at 28-bp sequence Bs dif 1. The site-specific recombinases are able to recognize two directly repeated dif sites and excise the fragment flanked by the two sites 2. Removal of a specific gene from a genome integrated construct: The site-specific recombinases, endogenous to B. subtilis strains are able to recognise dif sites and recombine out the strand of DNA directly flanked by the two sites. Recombination leaves a single dif site. The construct was previously engineered to homologously recobine into the genome of B. subtilis. Integration sequences such as amyE <bbpart>BBa_K143001</bbpart>, <bbpart>BBa_K143002</bbpart> can be used to achieve this. |

| References |

|

1) Sciochetti SA, Piggot PJ, and Blakely GW. Identification and characterization of the dif Site from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 2001 Feb; 183(3) 1058-68. doi:10.1128/JB.183.3.1058-1068.2001 pmid:11208805. PubMed HubMed 2) Bloor AE and Cranenburgh RM. An efficient method of selectable marker gene excision by Xer recombination for gene replacement in bacterial chromosomes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006 Apr; 72(4) 2520-5. doi:10.1128/AEM.72.4.2520-2525.2006 pmid:16597952.

Surplus information on B. Subtilis chassis [http://www.subtiwiki.uni-goettingen.de/wiki/index.php/Main_Page Subti-Wiki] 1) [http://mic.sgmjournals.org/cgi/content/full/146/12/3025 Fimbrial surface display systems in bacteria: from vaccines to random libraries. Klemm1 & Schembri, 2000] 2) [http://www.microbialcellfactories.com/content/5/1/22 Surface display of proteins by Gram-negative bacterial autotransporters. Rutherford & Mourez, 2006] 3) [http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/118603263/PDFSTART Protein cell surface display inGram-positive bacteria: fromsingle protein tomacromolecular protein structure. Desvaux et al, 2006] 4) [http://aac.asm.org/cgi/content/full/43/6/1459?view=long&pmid=10348770 Outer Membrane Permeability Barrier in Escherichia coli Mutants That Are Defective in the Late Acyltransferases of Lipid A Biosynthesis. Vaara1 & Nurminen, 1999] |

"

"