Team:BCCS-Bristol/Modelling/BSIM/GUI

From 2010.igem.org

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{:Team:BCCS-Bristol/Header}} | {{:Team:BCCS-Bristol/Header}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center> • '''[[:Team:BCCS-Bristol/Modelling/BSIM/Modelling_Environmental_Interactions|Modelling Environmental Interactions]]''' • '''Graphical User Interface''' • '''[[:Team:BCCS-Bristol/Modelling/BSIM/Results| Results]]''' • | ||

| + | '''[http://code.google.com/p/bsim-bccs/ Install BSIM]''' • </center> | ||

| + | |||

=Graphical User Interface (GUI)= | =Graphical User Interface (GUI)= | ||

Revision as of 19:47, 27 October 2010

iGEM 2010

Graphical User Interface (GUI)

Contents |

List of Supported Features

The new GUI supports many of the features of BSim 2009. These include:

- Brownian Motion

- Collisions

- Chemical fields

- Detection

- Chemical emission and consumption

- Colour signalling

- Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs)

- Variable boundary conditions

- Directed movement (Chemotaxis)

Development

Motivation

The 2009 edition of BSim was written using an object-oriented programming language called JAVA. This was an excellent tool in which to construct BSim, as it made it very easy to produce agent-based models. However, modelling a specific system in BSim required the user to edit JAVA code. We envision a future in which BSim is a widely used and accessible modelling framework. To achieve this we needed to create an interface that allows users unfamiliar with JAVA to create simulations in BSim. This would allow BSim to be utilised by the entire synthetic biology community, rather than just specialist modellers.

Graphical User Interface (GUI) -What's new?

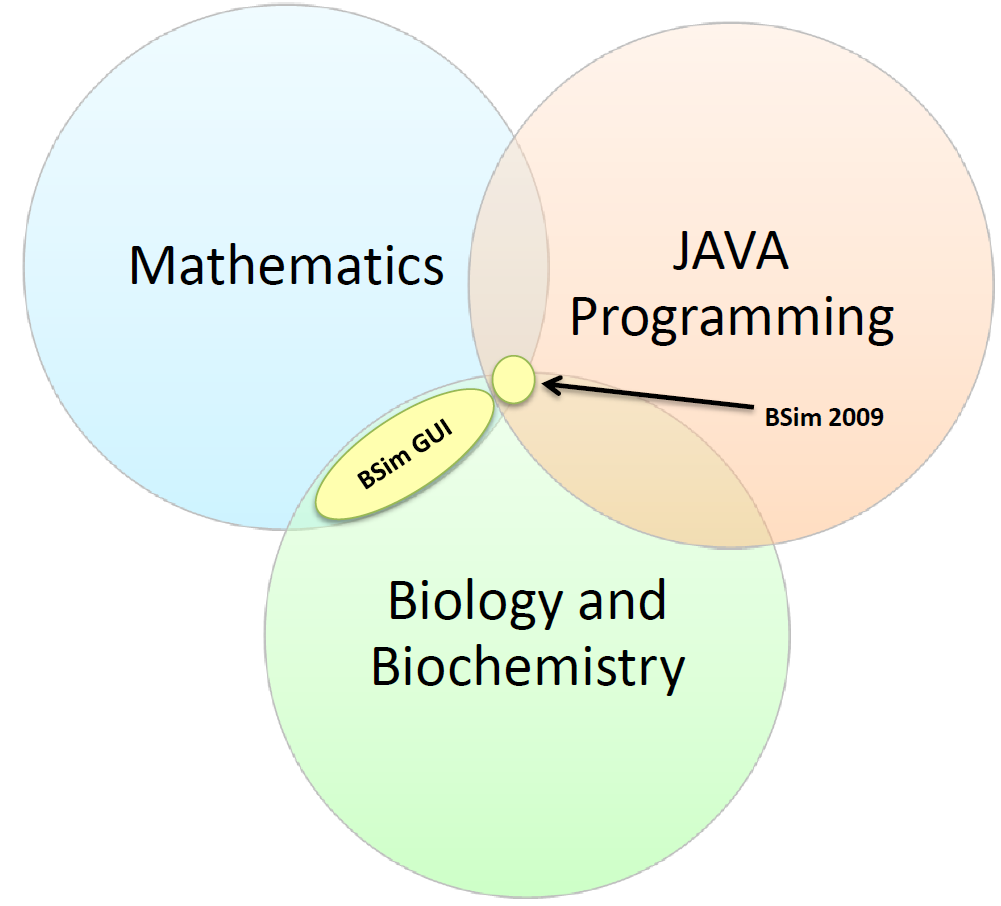

Past iGEM projects at BCCS-Bristol required knowledge of JAVA, mathematics and biochemistry. The 2009 edition of BSim relied heavily on the user’s knowledge of all three. By removing the need for JAVA knowledge, we have opened up BSim to a much wider category of users. The GUI only requires users to be able to express their biological system mathematically; it can then translate the user’s description of a system into JAVA code.

Who is the GUI aimed at?

The GUI is primarily aimed at users without any knowledge of JAVA. However, it is also of use to more advanced programmers, as it writes JAVA files that can be further modified using a text editor. This means advanced users can use the GUI to set a simple simulation which can be further tailored to their needs using JAVA. This saves a lot of time, as setting up a new simulation in BSim 2009 could take dozens of lines of code.

Simplifying BSim 2009

The main aims in creating the GUI were to reduce the time and background knowledge required to produce a BSim Simulation.

Creating Simulations in BSim 2009

The figure below shows the process of writing a simulation in the 2009 edition of BSim. All the steps of this process require knowledge of JAVA, and therefore are not accessible to the synthetic biological community in general. Additionally, there are too many steps in the process; slimming down the number of steps will make BSim easier to use.

The steps in the above process are described in more detail below:

- The first step in the process is the ‘imports’ step. This portion of a JAVA file lists all the other files that should be searched when a function is called. This allows a programmer to call functions defined elsewhere, rather than having to define them explicitly within the main JAVA file.

- Creating a blank simulation, is uniform across whatever type of simulation a user wishes to run. Once a blank simulation is created, it behaves like a workspace into which additional objects and behaviours can be added.

- Setting simulation options allows the user to specify the size and boundary conditions for the simulation.

- Defining bacterial classes involves specifying in detail the behaviour of any species of bacteria required in the simulation. This would also be the stage at which users would specify other objects, such as chemical fields or mesh shapes.

- Once the types of bacteria have been defined, users must specify how many of each type of bacteria they want added to the simulation, and where their initial positions are. BSim can allocate random initial positions if needed.

- The ‘ticker’ is a device that performs all the actions required during each time step. In general, the functions that are performed in each time step are defined before this point, and simply called within the ticker. The ticker also serves as the simulation clock, keeping track of how much time has passed.

- The drawer is where the display properties of objects are described. Once the existence of an object is stated (in step 3), the drawer only needs to be told what colour to display that object in.

- The final step requires the user to state how the simulation data should be expressed. This can be in the form of an immediate preview, a recorded movie or image, or as raw data in CSV (Comma Separated Variables) format.

Creating Simulations using the GUI

The figure below shows the process of creating a simulation using the new BSim GUI. Note that, by packaging many of the previous steps together, this new process is cut down to 4 compulsory and 1 optional step. Also, none of the compulsory steps require the user to understand JAVA code.

The first step in the process is completed automatically as soon as the GUI is opened, without any further user interaction. The next three compulsory steps are handled through dialog boxes that can be reached via the GUI 'Home' screen. Users are required to enter data in the form of numbers or mathematical equations, and can choose between options using intuitive scroll-down menus.

Interface Design

Home Screen

The 'Home' screen is designed to be the hub to which all the functions of the GUI connect. As such, no feature of the GUI is more than 3 mouse-clicks away from the Home screen. This helps to keep the interface intuitive, and easy to learn.

The Home screen is divided into 3 sections:

- Menu bar

- Button Panel

- Text Output Area

The menu bar allows the user to exit the program, and links to the 'About' section of the GUI. The button panel (to the left of the Home screen) guides the user through the steps needed to create a simulation. Each of the buttons either opens dialog boxes or executes code. Finally, the text output area keeps track of the options selected by the user, which is immensely useful when creating complicated simulations.

Simulation Options

The 'Simulation Options' dialog can be opened by clicking on the highlighted button on the Home screen.

The first option open to the user is the simulation size (in microns). This is in the form of {x,y,z} co-ordinates, and the shape specified will always be a cuboid, but does not have to be a cube. No matter what size or shape the user chooses, the simulation camera will zoom in or out to show the entire simulation space at a reasonable size.

The second option defines the boundary conditions on the simulation space. These are stated as three boolean (true/false) values, relating to the {x,y,z} planar boundaries of the simulation cuboid. When set to 'true', the planar boundaries become collidable, meaning that objects that intersect them bounce off elastically in the opposite direction. This behaviour preserves the 'conservation of momentum' condition. If a boundary condition is set to 'false', then the associated plan boundaries are periodic. This means that an object passing through the boundary of the simulation will instantly be transported to an exact opposite spatial position within the simulation. Objects re-appear with the same velocity as they had before, preserving conservation of momentum.

The final option in this dialog is the camera angle. This has to be stated in the form {i,j,k}, where i,j and k are real, positive numbers. The camera angle is calculated using the ratio of these three numbers.

Add Chemical Environment

The 'Add Chemical Environment' dialog can be opened by clicking on the highlighted button on the Home screen. Every simulation must have at least one chemical environment, even if it is empty. By adding a chemical environment, the user is creating an object which spans the entire simulation space and keeps track of the quantity of single species of chemical. There is no limit to the number of chemical environments that can be added to the simulation, but after adding 6 the user may run out of colours to display them in.

The diffusivity of a chemical field (in microns per second) defines how quickly a particular chemical spreads across the simulation space. The decay rate is the ratio of the chemical that breaks down every second. This must be a real number between 0 and 1.

Users can choose which colour to display a chemical in using the drop-down menu. Once users are happy with their choices, they can add the chemical field to the simulation by clicking on the button at the bottom of the dialog. This writes an empty chemical environment into the simulation JAVA file; to add any chemicals to this field, users must create a bacterial population and instruct them to interact with the relevant field. Once a chemical environment has been added, details about it are displayed in the text output area of the Home screen.

Future editions of the GUI will allow users to add to chemical fields without using bacterial populations. Users will also be able to give customised names to each field to aid their memories.

Add Bacteria

The 'Add Bacteria' dialog can be opened by clicking on the highlighted button on the Home screen. BSim works by defining a 'class' that defines the behaviour of a bacterial population. It later adds members of the population to the simulation as needed. The GUI preserves this method of doing things by asking users to describe the behaviour of a bacterial species before deciding how many of that species they wish to add, and where to put them.

Using this dialog box, users can create bacteria that:

- Detect chemicals

- Create chemicals

- Direct their movement in response to chemicals (Chemotax)

- Signal collisions

The first three of these features can be combined to model many useful population-level behaviours. Examples include quorum sensing, or chemical production in response to a non-homogenous chemical environment.

The final feature, collision signalling, is a very useful diagnostic tool. When a bacterium collides with another bacterium or a solid object, it changes colour. This lets the user know that collisions are working properly, and the total number of post-collision bacteria after a specified time interval can be used as a measure of bacterial motility or density.

Users can choose the initial colour and size of a bacterial population, and specify whether or not they move. For populations greater than 1, the GUI gives unique random initial positions to every bacterium in the population. This is done to avoid the situation in which several bacteria occupy the same space at the beginning of a simulation. For populations of exactly 1 bacterium, the user can specify the exact initial position of that bacterium. User-specified initial positions take priority over random assignments, meaning that no two bacteria will occupy the same area unless the simulation area is completely filled. Under default simulation settings, it would take 1 million bacteria to fill the simulation space. As such it is unlikely that this situation will ever arise.

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Dialog

Coupled ordinary differential equations are a standard method of describing the dynamics of enzyme kinetics and GRN models. Our GUI needed to have a good way of inputting coupled ODEs, ideally without having to know any JAVA. ODEs are not considered to be simple mathematics, so may not be accessible to all biologists. This is unfortunate, but can't be ascribed to the GUI, rather to the nature of ODEs themselves.

The ODE dialog opens when bacterial populations with either ODE signalling or ODE production rates are added. The dialog opens with the relevant production or signalling sections enabled. Users must then provide a vector of variables, the equations governing the way those variables change over time, and the initial values of each of those variables. The ODE equations may contain an unlimited (but finite) number of parameters, which can be defined in the central-left text box. The parameters could be constants, but could also be taken from the simulation environment. An example of this would be using the chemical concentration at the current location of a bacterium as a parameter.

ODEs can be used to define the change in colour of a bacterial population using the 'Signalling Chemical' text box. The 'Chemical Production Rate' text box can be used to make bacteria dump chemicals into the external environment at a nonlinear rate.

While it is possible to define simple ODE systems using maths alone, this dialog box also supports JAVA code. This means that advanced users can insert difficult or unusual behaviours directly, without having to edit the code later.

Displaying outputs from the GUI

The GUI supports 4 types of output:

- Previews

- Movies

- Pictures

- Raw Data

Previews create an instant pop-up window in which the BSim simulation is displayed. This allows users to swiftly check the validity of their simulation options. It is also a great way of rapidly demonstrating BSim.

Movies are produced in .MOV format, which is compatible with most common media players. Users are prompted to specify the length, speed and level of detail of the movie through a pop-up box. They can also choose where to save the file, and what to name it.

Pictures are produced in .PNG format, which is a useful format for web publishing and printing. Users can choose when to take a snapshot of their simulation and where to save it.

Raw Data is exported as a .CSV file. CSV stands for 'Comma Separated Values'; this is compatible with text editors, spreadsheet programs (e.g. MS Excel) and is very useful to plot graphs with.

"

"