Project safety

Safety Concerns During Election of Project

In electing a project there were numerous ideas to be considered. They were divided into the following categories: the environment, foods, health & disease, physics/chemistry/biochemistry and finally other which included some more artistic ideas along with a few humorous ones (like the jeopardy bacteria – knows all the right questions). Especially while thinking about medical ideas for implementing in the body we knew there were serious risk issues that had to be considered because of the many ways bacteria may interact with the human body.

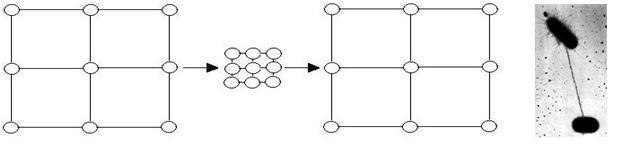

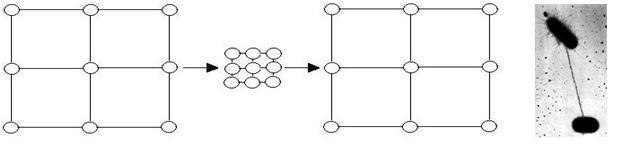

During our closer investigations of project ideas we also considered which bacteria it was possible to use. Our focus was to try and find a project that was possible to carry out by using E. coli. The reasons here for being that (cultivated strains of) E. coli are very well adapted to the laboratory environment since they are easy to keep alive, they can be fairly easy modified and unlike some wild strains of E. coli they no longer have the ability to thrive inside the intestines. Despite of these considerations we started out working on a project we called mE.chanic (because we wanted to make bacteria do mechanical work), and the idea was to have a culture of bacteria contract and relax, thereby making a pump-like movement creating mechanical work.

Our first project idea involved pili, but we decided it was unsafe, because of it's potential pathogenicity.

Now, we found out that we could use pili as some sort of ‘grappling hooks’ to make a connection between the bacteria. Pili from E.coli had been measured to have a pulling force of about 100 pN (enough to work a nano-machine), and so it seemed that we would have a good chance of making usable mechanical work if we continued this idea. We just needed to find out how to control the formation and retraction of the pili.

The project turned out to be most likely to succeed if we used the pathogenic bacteria Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, because it is very good at making the type VI pili we wanted. But, that is unfortunately due to its pathogenicity since the pili are an important part of this, as they are used for the bacteria to stay put and not get washed away. So using P. Aeruginosa was immediately out of the question because the risk of personal health (fx. getting a cystitis infection) for the researchers was too high, since they are students and not yet fully educated scientists. Also it would be a potential danger for the surrounding community if it spread. So instead we started to investigate the possibilities of using E. coli, but then found that [bacterial name] was a non-pathogenic bacteria with close resemblance to P. Aeruginosa, and also with resemblance to E.coli. So we started working with it. Eventually though, we had to discard this project idea on a safety basis: We had serious doubts that we could succeed with P. Aeruginosa, given that we basically didn’t believe the bacteria would function with all the genes we needed to provide it with (pili are virulence factors, and working with a non-pathogenic bacteria it would be less likely to make enough pili / keep its pili).

Then our thought was to use E. coli and provide it with pili, but this started a long discussion about whether this would make the E. coli potentially pathogenic. The end of the discussion was to give our project a big make-over keeping the concept of wanting to make mechanical work, but changing the idea of the actual mechanical work to be done.

We finally decided on the project of Bacterial Micro Flow, and the safety issues in relation to this project will be presented in the following. These include issues of researchers’ safety, public safety and environmental safety. We will also look at safety in relation to the specific biobricks we use and make, and will have a chapter on what the safety-staff at our university think of this project. Now, let us start at the lab.

Risk-assessment for Individual Parts

Here we consider the safety of each of our parts.

Methode

We have used our risk-assessment paper to describe the safety of each of our contributed parts. The genes were [http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi BLASTed] to find their function and known homologs. This function was then reasearched (mainly via [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed PubMed]), described and considered according to the questions asked in the risk-assessment paper.

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K343001 Monooxygenase (Part K343001)]

General use

This BioBrick poses no treat to the welfare of people working with it, as long as this is done in at least a level 1 safety lab by trained people. No special care is needed when working with this BioBrick.

Potential pathogenicity

The BioBrick’s product is not in itself toxic, but we do not recommend using this BioBrick for any type of system in humans or animals for the following reasons:

- Retinoic acid, which retinal can degrade into, can affect gene expression and function of almost any cell, including cells of the immune system; it also plays a fundamental role in cellular functions by activating nuclear receptors (1).

- Vitamin A toxicity can lead to hepatic congestion and fibrosis (2).

- Vitamin A and its derivatives have been implicated as chemopreventive and differentiating agents in a variety of cancers (3).

These effects are not directly associated with the enzyme itself, but have been observed in humans. It is highly unlikely that high enough doses can be reached with this biobrick. Please see references for more information about the diseases.

The biobrick has many homologs, that have the same function as this biobrick and is highly conserved in bacteria and eukaryotes. The biobrick does not affect the immunesystem in humans.

Environmental impact

To our knowledge retinal should not play a significant role in environmental processes or would disrupt natural occurring symbiosis.

The biobrick should not increase its host’s ability to spread, survive outside the laboratory, and will most likely decrease its ability to replicate.

Beta-caroten monooxygenase is found in a wide variety of different bacteria, insects and animals (4). As such we would be cautious as to letting a system containing this BioBrick into the wild, since it's function might conflict with existing systems. On the other hand one might argue that since it's function is already available in nature, the function is widely available.

The product of the BioBrick, retinal, also plays an important function in nature and animals. For this reason we fell that the BioBrick could be used in controlled settings, but not in the wild.

Possible malign use

There is not reason to believe this biobrick could be used for malign uses; it does not increase the hosts ability to vaporize, create spores, regulate the immunesystem or should be pathogenic.

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K343000 Hyperflagellation (Part K343000)]

General use

This BioBrick poses no treat to the welfare of people working with it, as long as this is done in at least a level 1 safety lab by trained people and in non-pathogenic hosts such as E. coli TOP10 or MG1655. No special care is needed when working with this BioBrick.

Potential pathogenicity

This biobrick increases the potential of its host to move. Increased motility has been associated the bacteria’s ability to invade humans (5); on the other hand it has also been shown that bacteria that loss the function of the FlhDC operon, are considerable better at colonizing the intestine (6), and so an increased expression might decrease a hosts ability to colonize and invade humans. It is impossible to ensure, that this plasmid is not transferred to pathogenic bacteria since the FlhDC operons is used in a wide array of other bacteria that are known to be pathogenic.

A number of effector cells in the human immune system react specifically to bacteria’s flagella, and so a hyperflagellated host will most likely induce a stronger immune response.

These different considerations lead us to conclude that we do not recommend using this BioBrick in humans.

Environmental impact

The biobrick might increase its host ability in finding foods, but we do not think it will be able to outmatch naturally occurring bacteria. It will not increase the hosts ability to replicate, but will increase its ability to spread, which might increase its ability to survive.

The biobrick itself will most likely not make an environmental impact, since it only regulates internal systems of the bacteria.

Possible malign use

There is no reason to believe this BioBrick could be used for malign uses; it does not increase the host’s ability to vaporize, create spores or ability to survive under storage conditions. The fact that this BioBrick will likely increase the immune systems response to hosts carrying it makes it a bad candidate for malign use.

[http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K343003 Photosensor (Part K343003)]

General use

This BioBrick poses no treat to the welfare of people working with it, as long as this is done in at least a level 1 safety lab by trained people. No special care is needed when working with this BioBrick.

Potential pathogenicity

This BioBrick consists of three different parts: The first 224 amino acid residues come from the NpSopII gene from halobacteria, encoding a blue-light photon receptor with 15 residues removed at the C-terminal. The following 9 amino acids are a linker. The last part is HtrII fused with Tsr from E. Coli. The complex' first 125 amino acid residues come from HtrII and the remaining 279 from Tsr (7). NpHtrII is thought to function in signal transduction and activation of microbial signalling cascades (8).

A single article has been written about haloarchaea in humans indicating that these played a role in patients with inflammatory bowl disease (9), but there is no evidence that the genes or near homologs, this BioBrick is made from, are involved in any disease process, toxic products or invasion properties. They do not regulate the immune system in any way.

Environmental impact

The BioBrick does not produce a product that is secreted into the environment, nor is it’s gene product itself toxic. It would not produce anything that distrupt natural occurring symbiosis.

The BioBrick might increase a bacteria’s ability to find nutrients and as such ease its ability to replicate and spread in certain dark environments. On the other hand the BioBrick is very large and this will naturally slow down its replication rate. Generally we do not believe this BioBrick will make its host able to outcompete natural occurring bacteria, simply because it’s function is not something that will give its host a functional advantage.

Possible malign use

This BioBrick will not increase it’s hosts ability to survive in storage conditions, to be arosoled, to be vaporized or create spores. None of its proteins regulate or affect the immune system or are pathogenic towards humans and animals.

References

- Spiegl N, Didichenko S, McCaffery P, Langen H, Dahinden CA. Human basophils activated by mast cell-derived IL-3 express retinaldehyde dehydrogenase-II and produce the immunoregulatory mediator retinoic acid. Blood. 2008 Nov 1;112(9):3762-71.

- Russell RM. The vitamin A spectrum: from deficiency to toxicity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 71, No. 4, 878-884, April 2000.

- Pasquali D, Thaller C, Eichele G. Abnormal level of retinoic acid in prostate cancer tissues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996 Jun;81(6):2186-91.

- Bryant DA, Frigaard N. Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated. Trends Microbiol. 2006 Nov;14(11):488-496.

- Young GM, Badger JL, Miller VL. Motility is required to initiate host cell invasion by Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect. Immun. 2000 Jul;68(7):4323-4326.

- Gauger EJ, Leatham MP, Mercado-Lubo R, Laux DC, Conway T, Cohen PS. Role of Motility and the flhDC Operon in Escherichia coli MG1655 Colonization of the Mouse Intestine. Infect. Immun. 2007 Jul 1;75(7):3315-3324.

- Jung KH, Spudich EN, Trivedi VD, Spudich JL. An archaeal photosignal-transducing module mediates phototaxis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2001 Nov;183(21):6365-6371.

- Mennes N, Klare JP, Chizhov I, Seidel R, Schlesinger R, Engelhard M. Expression of the halobacterial transducer protein HtrII from Natronomonas pharaonis in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 2007 Apr 3;581(7):1487-1494.

- Oxley APA, Lanfranconi MP, Würdemann D, Ott S, Schreiber S, McGenity TJ, et al. Halophilic archaea in the human intestinal mucosa. Environ Microbiol [Internet]. 2010 Apr 23 [cited 2010 Oct 26];Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20438582

"

"