Team:Duke/Project

From 2010.igem.org

| (57 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

.links { | .links { | ||

| + | text-align: center; | ||

background-color:rgb(0,64,128); | background-color:rgb(0,64,128); | ||

margin-bottom:0px; | margin-bottom:0px; | ||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

text-decoration: none; | text-decoration: none; | ||

font-size: 16pt; | font-size: 16pt; | ||

| - | font-weight: | + | font-weight: normal; |

font-family: century gothic,Arial, sans-serif; | font-family: century gothic,Arial, sans-serif; | ||

color: rgb(140,200,250); | color: rgb(140,200,250); | ||

| Line 19: | Line 20: | ||

#nav a { | #nav a { | ||

| - | + | display: block; | |

| - | display : block; | + | |

color : rgb(255,255,255); | color : rgb(255,255,255); | ||

font-weight : bold; | font-weight : bold; | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

color : rgb(0,64,128); | color : rgb(0,64,128); | ||

font-weight : normal; | font-weight : normal; | ||

| - | font-size: | + | font-size: 10pt; |

font-family:century gothic, Arial, sans-serif; | font-family:century gothic, Arial, sans-serif; | ||

text-align : center; | text-align : center; | ||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

#nav2 a:hover { | #nav2 a:hover { | ||

font-weight: bold; | font-weight: bold; | ||

| - | color : rgb(0, | + | color : rgb(0,64,128); |

} | } | ||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

<table class="links" width= "960px"> | <table class="links" width= "960px"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <img src= "https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/a/a4/DukeChapel.jpg" width= "960px"> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | |||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| - | <td | + | <td width= "150px" height= "40px"><a href="http://www.duke.edu"><font face= "Garamond" size= "6" color="white"> دوک </font> <font face= "interstate" size="2" color="white"> <b> i G E M </b> </font> </a></td> |

| - | + | <td width= "150px" id = "nav"><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Duke">home</a></td> | |

| - | <td | + | <td width= "150px"><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Duke/Project"> <b> project </b> </a></td> |

| - | <td id= "nav"><a href="Team:Duke/Team">about us</a></td> | + | <td width= "150px" id= "nav"><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Duke/Team">about us</a></td> |

| - | <td width = " | + | <td width = "360px"> </td> |

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | |||

<table class="sub" width= "960px"> | <table class="sub" width= "960px"> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| - | <td width = " | + | <td align= "center" width = "160px"><a href= "Team:Duke/Project"> Details </a></td> |

| + | <td width = "160px" id="nav2"><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Duke/Project/Notebook"> Notebook </a></td> | ||

| + | <td width = "160px" id="nav2"><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Duke/Project/Biobricks"> Biobricks </a></td> | ||

| + | <td width = "160px" id="nav2"><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Duke/Project/Protocols"> Protocols</a></td> | ||

| + | <td width = "160px" id="nav2"><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Duke/Project/Judging"> Judging/Safety</a></td> | ||

| + | <td width = "160px" height="19px"> </td> | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | =Modular Regulatory Toolkit using Protein Sequestration= | ||

| - | |||

| + | ==Introduction== | ||

| - | + | Bistable switches for gene expression, or "toggle switches" are ubiquitous in the design of synthetic expression pathways (8,9,14,18). Current designs for bistable switches frequently exhibit errors in their functioning due to promoter leakiness or basal regulatory noise (8,9). The purpose of this project is to develop a series of regulatory transistors based on protein sequestration that are highly robust, eliminate basal production noise and can be used to produce a tunable toolkit for modular gene expression. These designed circuits would be composed of both leucine zippers Fos and Jun, and synthetic dominant negatives thereof. | |

| + | Problems caused by the use of present toggle switches include a lack of tunability in regards to the rate of expression of either state, and a lack of consistence in gene expression due to noise (5,8,9). The proposed design would produce a transistor circuit that would be tunable (1) , highly robust (1,12,13), and capable of multistable or oscillatory functionality (7,8) as well as ultrasensitivity(1,2). The model circuit would consist of synthetic variants of basic leucine zippers c-fos and c-jun, and the dominant negative of these constructs, modified from A-fos (12), which would function to regulate gene expression according to a titration model, thereby eliminating the problems caused by cellular noise and basal regulator production. As a part of this project we would further attempt to characterize a broader variety of synthetic leucine zippers in order to generate a modular toolkit for the construction of similar transistor and amplifier devices. | ||

| - | </ | + | ==Leucine Zippers== |

| + | Basic Leucine Zippers (bZIPs) c-Fos and c-Jun are very well characterized, as their function in eukaryotes as growth regulators and protooncogenes is the subject of much discussion (4,11,12,13,15). Their functioning as heterodimerizing regulator proteins (4) has lead to the development of competitive inhibitors to their functioning by the generation of dominant negatives (12). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Heterodimerized Fos and Jun proteins interact with a DNA recognition sequence commonly referred to as the AP-1 site (4,11,15), which is not found in prokaryotes, meaning that this pathway would be unlikely to interfere with in vivo cellular functions in recombinant E coli. We intend to produce promoters for these dimerized proteins by replacing the binding sites of the cI promoter with AP-1 sites, as has been an effective method for custom promoter design (10,11,16,17). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The proposed regulatory pathway has previously been modeled in a series of papers by Francois & Hakim (7,8), as well as Buchler (2), and similar pathways have been found to be functional in yeast using mammalian bZIP CEBPα and its dominant negative 3HF (1). In these studies, similar dimerization pathways were shown to remove basal noise in regulatory protein expression by using protein sequestration. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Leucine zippers form heterodimers based on the specificity of their coiled-coil structure, and it has been repeatedly observed that altering the structure of these helices, either by single point mutations or helicle exchange, can lead to a change in dimerization specificity (12,13,15). A library of synthetic proteins based on leucine zipper design would yield a very broad spectrum of regulatory properties based on their heterodimerization and DNA binding rates (14,18), and the tunability of such a system would make it ideal for metabolic engineering (8,14,18). | ||

| + | |||

| + | DNA binding sites on leucine zippers also contribute to their regulatory properties (3,11,12,13,15), and it has been stipulated that by altering the DNA binding sequence it would be possible to generate a broad variety of specificities, that along with promoters generated with specific binding sites for the synthetic dimers would allow for the production of highly complex and tunable regulatory pathways. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There is great potential for modularity in the production of synthetic leucine zippers in that the DNA binding and dimerizing motifs that are present in bZIPs have been intensively studied and found to be distinct and recurring structural motifs in isolation of spacing sequences, meaning that synthetic zippers would be produced with essentially interchangeable parts to provide them with unique specificity (11,12). | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; width: 772px;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[Image:Leucine.JPG| 250px]] | ||

| + | | [[Image:Protein_sequestering_switch.JPG | 200px ]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Design== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The research will be conducted by generating a variety of synthetic bZIPs with unique dimerizing specificities, initially by using design methods originally proposed by Krylov & Vinson (12), then by using a variation of the Random Assembly PCR method initially pioneered by the Heidelberg 2009 iGEM team to produce a helix and binding site library (https://2009.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project_Synthetic_promoters#References). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Dominant negatives of the leucine zippers would be produced by both the original method determined by Charles Vinson (12) and by in silico design and synthesis based on specificity to dimer and binding sequences, as well as by recombining recognition sequences of existing leucine zippers. As there are hundreds of mammalian leucine zippers with independent dimerization sequences and largely conserved structure (12) this would allow for the generation of a very large toolkit of promoters regulated by uniquely specific leucine zippers.(1,4,12,15) | ||

| + | Leucine zippers have very specific DNA binding sites, so in order to design promoters that responded to them, we would replace the cI repressor binding sites in the cI promoter, thereby preventing transcription once the zippers were bound. (10,16,17) | ||

| + | Synthetic leucine zippers will be characterized by their dimerization and DNA binding specificities using a series of fluorometry assays tracking reporter gene expression rates, and cross dimerization between synthetic leucine zippers will be analyzed with an in vitro protein interaction assay that was initially used to characterize the dimerization properties of Fos and Jun (15). | ||

| + | Significance: | ||

| + | Tunable gene expression has been found to be of great use in the development of synthetic biological systems (14), and basal regulatory noise is often problematic in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology (8,9). The characterization of a toolkit to provide modular and tunable gene expression would allow synthetic biologists to design and produce complex expression pathways by making consistent and robust gene regulation methods more easily available. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =High Throughput Expression Screening of Synthetic Gene Libraries= | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introduction== | ||

| + | For the application of this project and others, we are developing a gene expression screen to match the high throughput of DNA synthesis machines. This would allow us to synthesize combinatorical gene libraries of codon variants, and then characterize each variant's effect on gene expression. We hope that this would allow for a user to generate a library gfp fusion protein, and pick from a database of empirically determined gene expression levels. This would allow for the possibility of 'tunable gene expression levels'. | ||

| + | |||

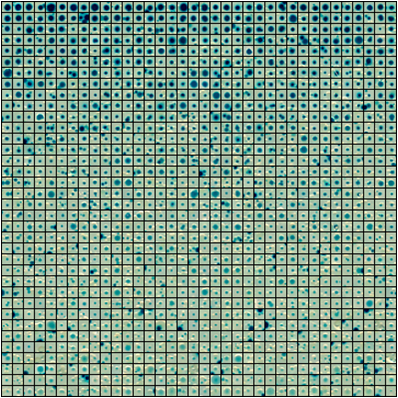

| + | <center>[[Image:Htexsc1.png| 234px]]</center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Design== | ||

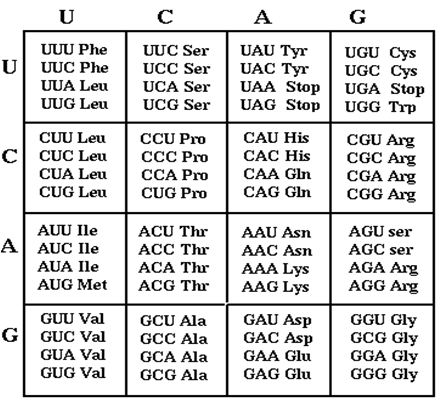

| + | Genes are composed of tri-nucleotide codons, each translating an amino acid. Each amino acid has redundant codons. It is acknowledged that optimal codons help achieve increased protein expression levels. We are generating many combinatorial codon orientations in order to modulate or improve a protein's expression level for specific design constraints. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A laboratory DNA synthesizer was used for degenerate oligonucleotide synthesis of gene fragments. By substituting a random base pair every third base pair in the sequence, a library of codon variants is generated. Using circular polymerase extension cloning (https://2009.igem.org/Team:Duke), these libraries are transformed into bacterial colonies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; width: 772px; height: 200px;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[Image:Htexsc2.png| 250px]] | ||

| + | | [[Image:Htexsc3.png| 150x400px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

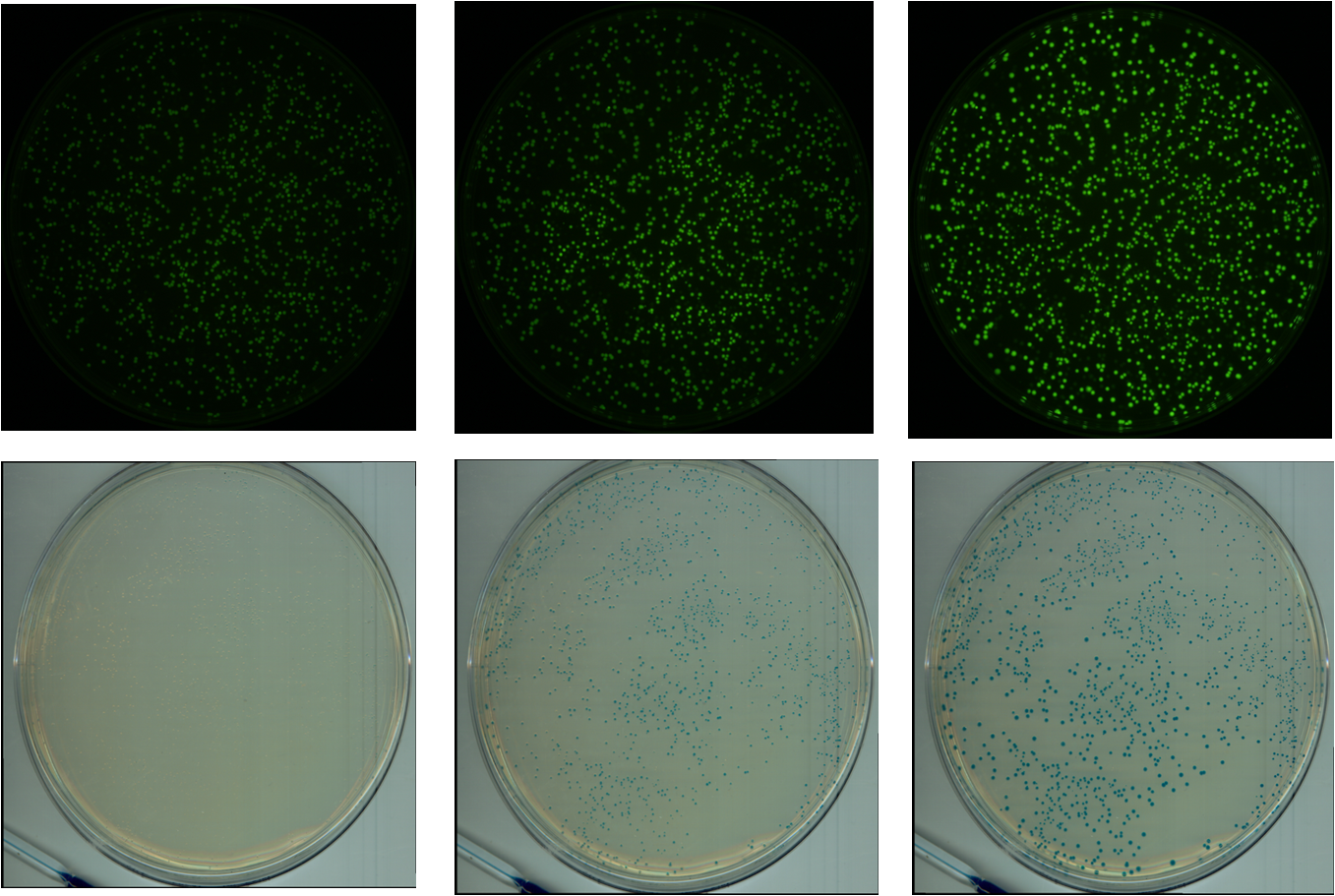

| + | We chose GFP (BBa_K411237) and LacZ (BBa_E0033) to analyze gene expression. GFP is green fluorescent under blue light excitation, and LacZ protein reacts with X-Gal substrate, turning blue. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center>[[Image:Htexsc4.png| 434px]]</center> | ||

| + | |||

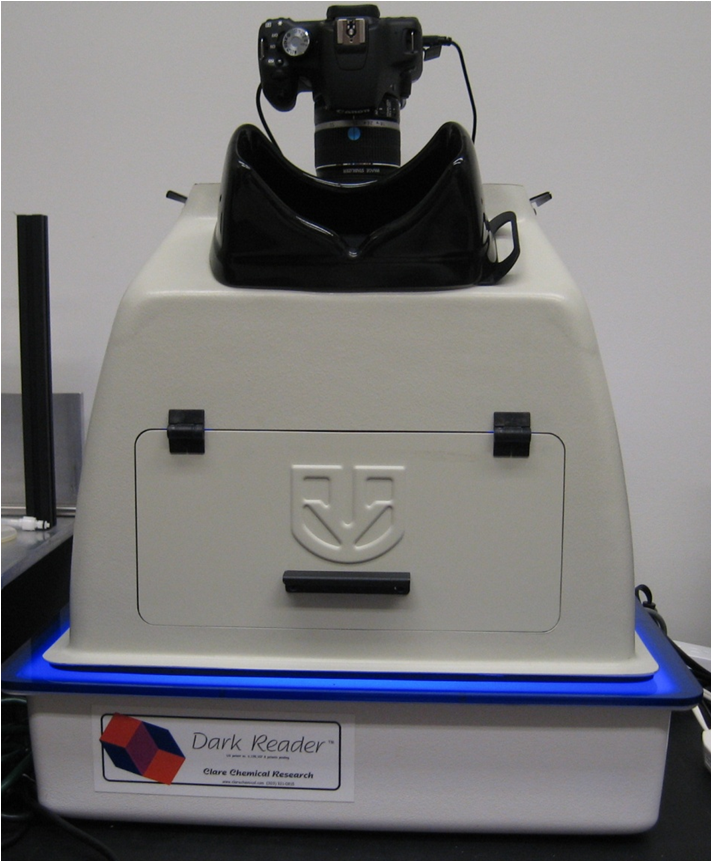

| + | A flatbed scanner and camera platform were used to obtain time lapse expression information from LacZ and GFP expressing E. coli colonies in solid culture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center; width: 960px; height: 200px;" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[Image:Htexsc5.png|275px]] | ||

| + | | [[Image:Htexsc6.jpg|300px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image analysis techniques were used to efficiently and automatically extract, evaluate, and correlate growth and expression information. CellProfiler was used to identify bacterial colonies. A mixture-of-Gaussian automatic thresholding method was used. Gene expression is correlated with pixel intensity. This way, expression data can be obtained. Colonies can then be picked for further analysis or sequencing. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <center>[[Image:Htexsc7.png| 434px]]</center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Verification== | ||

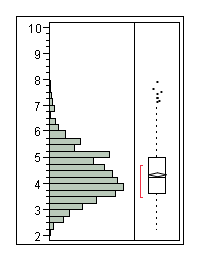

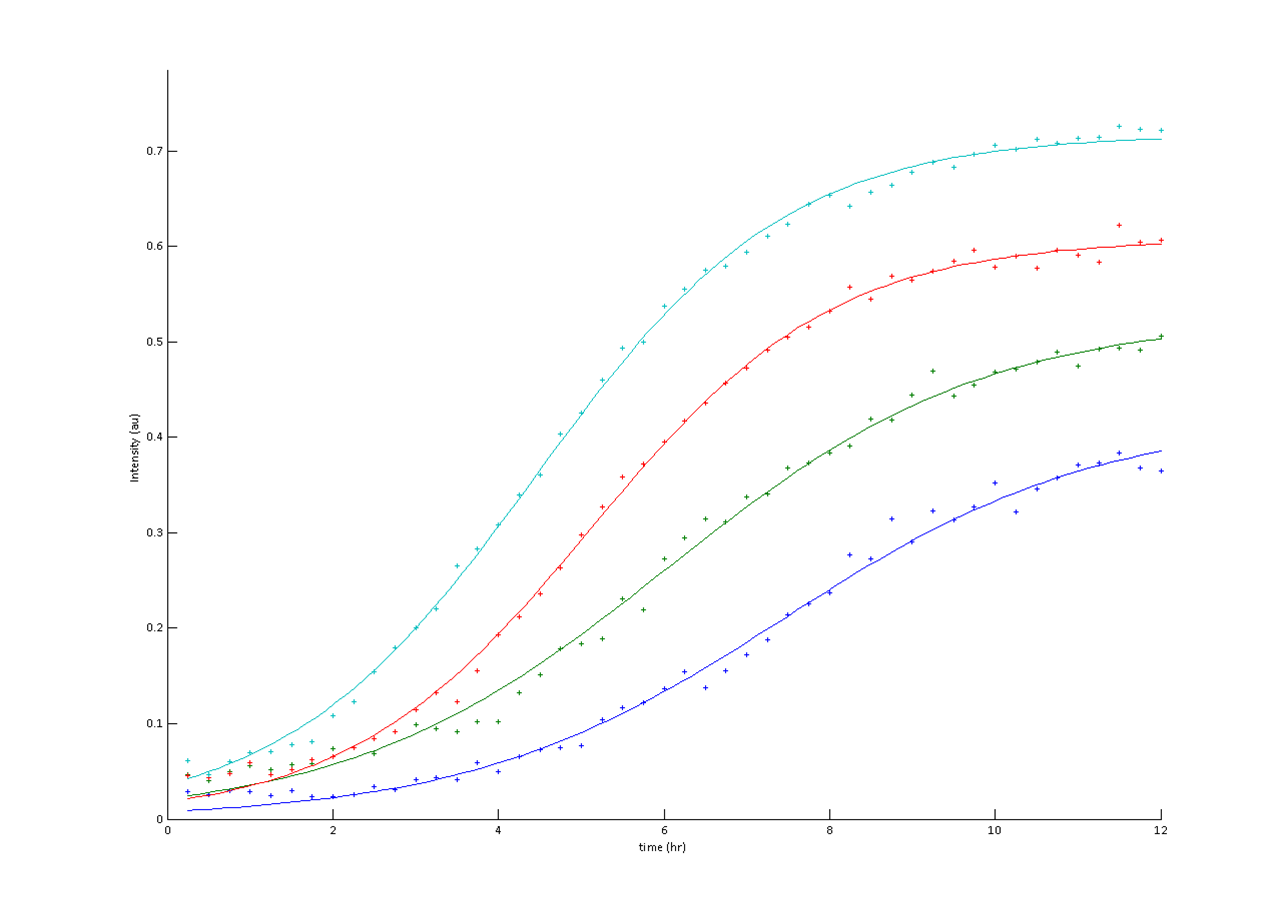

| + | The following half time distributions illustrate the differences between populations of E. coli expressing LacZ. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Htexsc8.png]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Htexsc9.png| 400px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | =References= | ||

| + | |||

| + | (1) Buchler, ND, & Cross, FR. (2009). Protein sequestration generates a flexible ultrasensitive response in a genetic network. Mol. Syst. Biol, 5(272), | ||

| + | |||

| + | (2) Buchler, ND, & Louis, M. (2008). Molecular titration and ultrasensitivity in regulatory networks. J. Mol. Biol., 384(1106-1119), | ||

| + | |||

| + | (3) Busch, Et al. Dimers, leucine zippers and dna binding domains. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (4) Deppmann, Et al. (2004). Dimerization specificity of all 67 b-zip motifs in arabidopsis thaliana: a comparison to homo sapiens b-zip motifs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (5) Dubnan, D, & Losich, R. Bistability in bacteria. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (6) Francois, P, & Hakim, V. (2005). Core genetic module: the mixed feedback loop. Laboratoire de Physique Statistique, | ||

| + | |||

| + | (7)Francois, P, & Hakim, V. (2004). Design of genetic networks with specified functions. Laboratoire de Physique Statistique, | ||

| + | |||

| + | (8) Gardner, Et al. (2000). Bistable genetic toggle switch: us patent 6841376 . | ||

| + | |||

| + | (9) Gardner, Et al. (2000). Construction of a genetic toggle switch in escherichia coli. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (10) Hochschild, Et al. Repressor structure and the mechanism of positive control. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (11) Jerome, Et al. A Synthetic leucine zipper- based dimerization system for combining multiple promoter specificities. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (12) Krylov A, & Vinson, C (1995). A General method to design dominant negatives to b-hlhzip proteins that abolish dna binding . | ||

| + | |||

| + | (13) Matthias, Et al. Dna binding of jun and fos bzip domains: homodimers and heterodimers induce a dna conformational change. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (14) Mijakovic, Et al. (2005). Tunable promoters in systems biology. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (15) Patel, Et al. Energy transfer analysis of fos-jun dimerization and dna binding. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (16) Ptashne, Mark. A Genetic switch: phage lambda and higher organisms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (17) Walz, Et al. Lambda repressor regulates the switch between pr and prm promoters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | (18) Westerhoff, HV, & van Workum, M. (1990). Control of dna structure and gene expression. Pubmed, PMID 1964556. | ||

Latest revision as of 20:55, 27 October 2010

| دوک i G E M | home | project | about us |

| Details | Notebook | Biobricks | Protocols | Judging/Safety |

Contents |

Modular Regulatory Toolkit using Protein Sequestration

Introduction

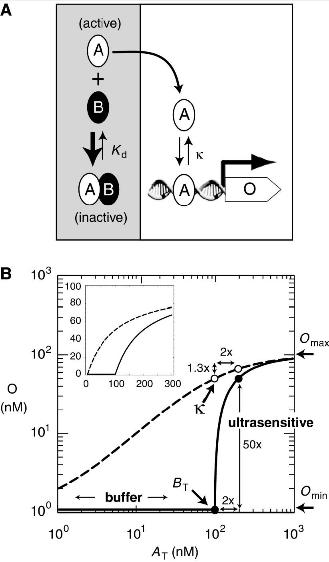

Bistable switches for gene expression, or "toggle switches" are ubiquitous in the design of synthetic expression pathways (8,9,14,18). Current designs for bistable switches frequently exhibit errors in their functioning due to promoter leakiness or basal regulatory noise (8,9). The purpose of this project is to develop a series of regulatory transistors based on protein sequestration that are highly robust, eliminate basal production noise and can be used to produce a tunable toolkit for modular gene expression. These designed circuits would be composed of both leucine zippers Fos and Jun, and synthetic dominant negatives thereof.

Problems caused by the use of present toggle switches include a lack of tunability in regards to the rate of expression of either state, and a lack of consistence in gene expression due to noise (5,8,9). The proposed design would produce a transistor circuit that would be tunable (1) , highly robust (1,12,13), and capable of multistable or oscillatory functionality (7,8) as well as ultrasensitivity(1,2). The model circuit would consist of synthetic variants of basic leucine zippers c-fos and c-jun, and the dominant negative of these constructs, modified from A-fos (12), which would function to regulate gene expression according to a titration model, thereby eliminating the problems caused by cellular noise and basal regulator production. As a part of this project we would further attempt to characterize a broader variety of synthetic leucine zippers in order to generate a modular toolkit for the construction of similar transistor and amplifier devices.

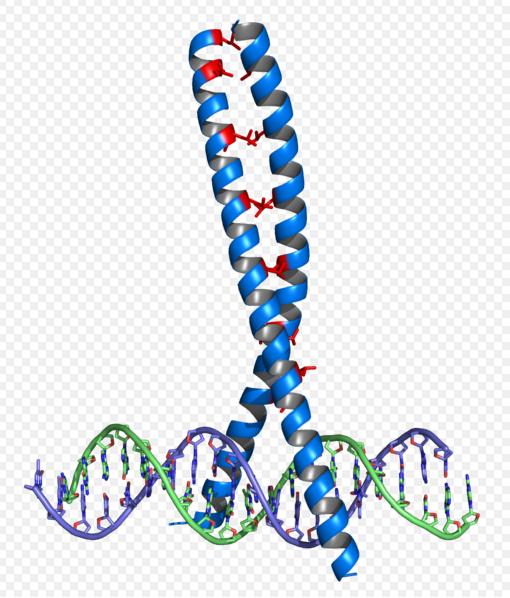

Leucine Zippers

Basic Leucine Zippers (bZIPs) c-Fos and c-Jun are very well characterized, as their function in eukaryotes as growth regulators and protooncogenes is the subject of much discussion (4,11,12,13,15). Their functioning as heterodimerizing regulator proteins (4) has lead to the development of competitive inhibitors to their functioning by the generation of dominant negatives (12).

Heterodimerized Fos and Jun proteins interact with a DNA recognition sequence commonly referred to as the AP-1 site (4,11,15), which is not found in prokaryotes, meaning that this pathway would be unlikely to interfere with in vivo cellular functions in recombinant E coli. We intend to produce promoters for these dimerized proteins by replacing the binding sites of the cI promoter with AP-1 sites, as has been an effective method for custom promoter design (10,11,16,17).

The proposed regulatory pathway has previously been modeled in a series of papers by Francois & Hakim (7,8), as well as Buchler (2), and similar pathways have been found to be functional in yeast using mammalian bZIP CEBPα and its dominant negative 3HF (1). In these studies, similar dimerization pathways were shown to remove basal noise in regulatory protein expression by using protein sequestration.

Leucine zippers form heterodimers based on the specificity of their coiled-coil structure, and it has been repeatedly observed that altering the structure of these helices, either by single point mutations or helicle exchange, can lead to a change in dimerization specificity (12,13,15). A library of synthetic proteins based on leucine zipper design would yield a very broad spectrum of regulatory properties based on their heterodimerization and DNA binding rates (14,18), and the tunability of such a system would make it ideal for metabolic engineering (8,14,18).

DNA binding sites on leucine zippers also contribute to their regulatory properties (3,11,12,13,15), and it has been stipulated that by altering the DNA binding sequence it would be possible to generate a broad variety of specificities, that along with promoters generated with specific binding sites for the synthetic dimers would allow for the production of highly complex and tunable regulatory pathways.

There is great potential for modularity in the production of synthetic leucine zippers in that the DNA binding and dimerizing motifs that are present in bZIPs have been intensively studied and found to be distinct and recurring structural motifs in isolation of spacing sequences, meaning that synthetic zippers would be produced with essentially interchangeable parts to provide them with unique specificity (11,12).

|

|

Design

The research will be conducted by generating a variety of synthetic bZIPs with unique dimerizing specificities, initially by using design methods originally proposed by Krylov & Vinson (12), then by using a variation of the Random Assembly PCR method initially pioneered by the Heidelberg 2009 iGEM team to produce a helix and binding site library (https://2009.igem.org/Team:Heidelberg/Project_Synthetic_promoters#References).

Dominant negatives of the leucine zippers would be produced by both the original method determined by Charles Vinson (12) and by in silico design and synthesis based on specificity to dimer and binding sequences, as well as by recombining recognition sequences of existing leucine zippers. As there are hundreds of mammalian leucine zippers with independent dimerization sequences and largely conserved structure (12) this would allow for the generation of a very large toolkit of promoters regulated by uniquely specific leucine zippers.(1,4,12,15) Leucine zippers have very specific DNA binding sites, so in order to design promoters that responded to them, we would replace the cI repressor binding sites in the cI promoter, thereby preventing transcription once the zippers were bound. (10,16,17) Synthetic leucine zippers will be characterized by their dimerization and DNA binding specificities using a series of fluorometry assays tracking reporter gene expression rates, and cross dimerization between synthetic leucine zippers will be analyzed with an in vitro protein interaction assay that was initially used to characterize the dimerization properties of Fos and Jun (15). Significance: Tunable gene expression has been found to be of great use in the development of synthetic biological systems (14), and basal regulatory noise is often problematic in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology (8,9). The characterization of a toolkit to provide modular and tunable gene expression would allow synthetic biologists to design and produce complex expression pathways by making consistent and robust gene regulation methods more easily available.

High Throughput Expression Screening of Synthetic Gene Libraries

Introduction

For the application of this project and others, we are developing a gene expression screen to match the high throughput of DNA synthesis machines. This would allow us to synthesize combinatorical gene libraries of codon variants, and then characterize each variant's effect on gene expression. We hope that this would allow for a user to generate a library gfp fusion protein, and pick from a database of empirically determined gene expression levels. This would allow for the possibility of 'tunable gene expression levels'.

Design

Genes are composed of tri-nucleotide codons, each translating an amino acid. Each amino acid has redundant codons. It is acknowledged that optimal codons help achieve increased protein expression levels. We are generating many combinatorial codon orientations in order to modulate or improve a protein's expression level for specific design constraints.

A laboratory DNA synthesizer was used for degenerate oligonucleotide synthesis of gene fragments. By substituting a random base pair every third base pair in the sequence, a library of codon variants is generated. Using circular polymerase extension cloning (https://2009.igem.org/Team:Duke), these libraries are transformed into bacterial colonies.

|

|

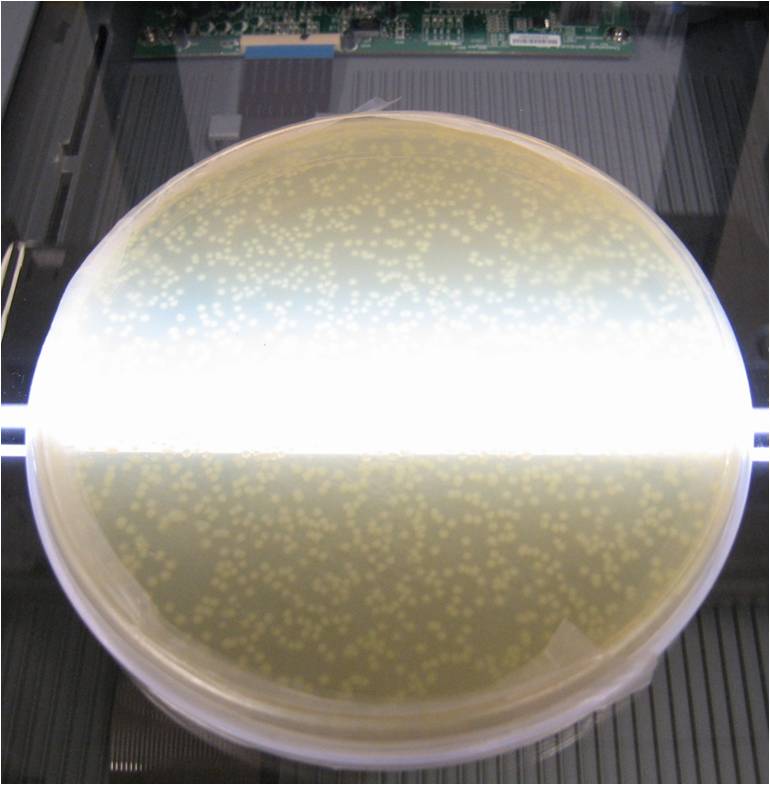

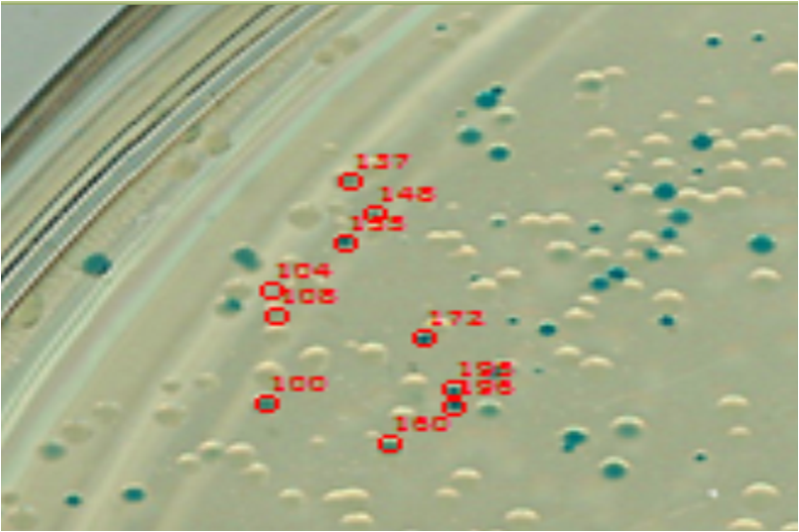

We chose GFP (BBa_K411237) and LacZ (BBa_E0033) to analyze gene expression. GFP is green fluorescent under blue light excitation, and LacZ protein reacts with X-Gal substrate, turning blue.

A flatbed scanner and camera platform were used to obtain time lapse expression information from LacZ and GFP expressing E. coli colonies in solid culture.

|

|

Image analysis techniques were used to efficiently and automatically extract, evaluate, and correlate growth and expression information. CellProfiler was used to identify bacterial colonies. A mixture-of-Gaussian automatic thresholding method was used. Gene expression is correlated with pixel intensity. This way, expression data can be obtained. Colonies can then be picked for further analysis or sequencing.

Verification

The following half time distributions illustrate the differences between populations of E. coli expressing LacZ.

References

(1) Buchler, ND, & Cross, FR. (2009). Protein sequestration generates a flexible ultrasensitive response in a genetic network. Mol. Syst. Biol, 5(272),

(2) Buchler, ND, & Louis, M. (2008). Molecular titration and ultrasensitivity in regulatory networks. J. Mol. Biol., 384(1106-1119),

(3) Busch, Et al. Dimers, leucine zippers and dna binding domains.

(4) Deppmann, Et al. (2004). Dimerization specificity of all 67 b-zip motifs in arabidopsis thaliana: a comparison to homo sapiens b-zip motifs.

(5) Dubnan, D, & Losich, R. Bistability in bacteria.

(6) Francois, P, & Hakim, V. (2005). Core genetic module: the mixed feedback loop. Laboratoire de Physique Statistique,

(7)Francois, P, & Hakim, V. (2004). Design of genetic networks with specified functions. Laboratoire de Physique Statistique,

(8) Gardner, Et al. (2000). Bistable genetic toggle switch: us patent 6841376 .

(9) Gardner, Et al. (2000). Construction of a genetic toggle switch in escherichia coli.

(10) Hochschild, Et al. Repressor structure and the mechanism of positive control.

(11) Jerome, Et al. A Synthetic leucine zipper- based dimerization system for combining multiple promoter specificities.

(12) Krylov A, & Vinson, C (1995). A General method to design dominant negatives to b-hlhzip proteins that abolish dna binding .

(13) Matthias, Et al. Dna binding of jun and fos bzip domains: homodimers and heterodimers induce a dna conformational change.

(14) Mijakovic, Et al. (2005). Tunable promoters in systems biology.

(15) Patel, Et al. Energy transfer analysis of fos-jun dimerization and dna binding.

(16) Ptashne, Mark. A Genetic switch: phage lambda and higher organisms.

(17) Walz, Et al. Lambda repressor regulates the switch between pr and prm promoters.

(18) Westerhoff, HV, & van Workum, M. (1990). Control of dna structure and gene expression. Pubmed, PMID 1964556.

"

"