Team:Lethbridge/Results

From 2010.igem.org

Adam.smith4 (Talk | contribs) (→Results) |

JustinVigar (Talk | contribs) (→Method) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

=<font color="white">Catechol Degradation= | =<font color="white">Catechol Degradation= | ||

| - | The focus of our <html><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Lethbridge/Project"><font color="#00DC00">project</font></a></html> is to decrease the toxicity of | + | The focus of our <html><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Lethbridge/Project"><font color="#00DC00">project</font></a></html> is to decrease the toxicity of tailings pond water through bioremediation. We are specifically interested in the <html><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:Lethbridge/Project/Catechol_Degradation"><font color="#00DC00">degradation of the toxic molecule catechol</font></a></html> into 2-hydroxymuconate semialdyhyde (2-HMS); a bright yellow substrate that can be metabolized by the cell. This conversion is accomplished by a protein called catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (xylE). |

==<font color="white">Characterization of Catechol 2,3-Dioxygenase== | ==<font color="white">Characterization of Catechol 2,3-Dioxygenase== | ||

| Line 200: | Line 200: | ||

Catechol 2,3-dioxygenase contains an iron molecule in its active site. Our hypothesis was that the iron molecule is oxidized after converting a single catechol molecule to 2-HMS; rendering the catechol 2,3-dioxygenase inactive. We also want to test how catechol 2,3-dioxygenase would behave <i>in vitro</i> compared to <i>in vivo</i>. | Catechol 2,3-dioxygenase contains an iron molecule in its active site. Our hypothesis was that the iron molecule is oxidized after converting a single catechol molecule to 2-HMS; rendering the catechol 2,3-dioxygenase inactive. We also want to test how catechol 2,3-dioxygenase would behave <i>in vitro</i> compared to <i>in vivo</i>. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| - | To test this hypothesis we grew <i>E. coli</i> containing BBa_K118021 in 500 mL of LB media with ampicillin. <i>E.coli</i> containing the pUC19 plasmid were also grown in 500 mL of LB media with ampicillin to act as a negative control throughout the course of the experiment. The cells were grown to a final optical density of 4.55 AU (measured at 600 nm). The cells were first spun down at 3800 rcf for 5 minutes. The supernatant was decanted and the cells were re-suspended in 40 mL M9 minimal media and incubated with 10 mg of lysozyme for 10 minutes. This cell extract was spun down at 10000 rcf for 30 minutes. The supernatant was taken off and spun at 30000 rcf (S30) for 1 hour. The supernatant of the S30 samples was divided. Half the samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80<sup>o</sup>C. The second half was spun at 100000 rcf for 45 minutes. | + | To test this hypothesis we grew <i>E. coli</i> containing BBa_K118021 in 500 mL of LB media with ampicillin. <i>E.coli</i> containing the pUC19 plasmid were also grown in 500 mL of LB media with ampicillin to act as a negative control throughout the course of the experiment. The cells were grown to a final optical density of 4.55 AU (measured at 600 nm). The cells were first spun down at 3800 rcf for 5 minutes. The supernatant was decanted and the cells were re-suspended in 40 mL M9 minimal media and incubated with 10 mg of lysozyme for 10 minutes. This cell extract was spun down at 10000 rcf for 30 minutes. The supernatant was taken off and spun at 30000 rcf (S30) for 1 hour. The supernatant of the S30 samples was divided. Half the samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80<sup>o</sup>C. The second half was spun at 100000 rcf for 45 minutes (S100). |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

In order to measure the 2-HMS production we needed to determine the concentration of protein per volume of cell extract. To determine the total protein concentration of the S30 and S100 extracts a Bradford assay was conducted using a standard curve of BSA. Concentrations of the negative controls (<i>Escherichia coli</i> DH5α hosting the pUC19 plasmid) for each of the S30 and S100 samples were also determined. Absorbance readings were taken at a 595 nm wavelength and concentration reported in µg/mL. | In order to measure the 2-HMS production we needed to determine the concentration of protein per volume of cell extract. To determine the total protein concentration of the S30 and S100 extracts a Bradford assay was conducted using a standard curve of BSA. Concentrations of the negative controls (<i>Escherichia coli</i> DH5α hosting the pUC19 plasmid) for each of the S30 and S100 samples were also determined. Absorbance readings were taken at a 595 nm wavelength and concentration reported in µg/mL. | ||

| Line 222: | Line 222: | ||

===<font color="white">Results=== | ===<font color="white">Results=== | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

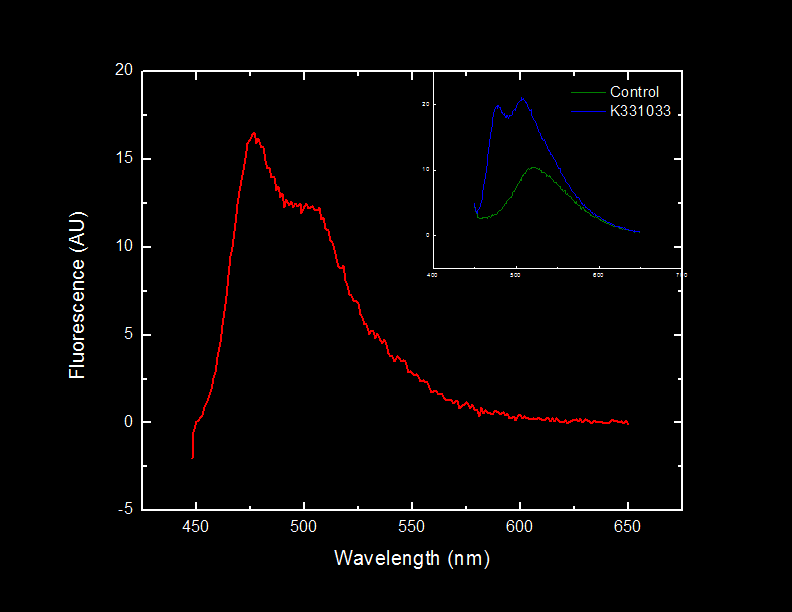

| - | Figure 3 displays that catechol 2,3-dioxygenase can degrade catechol <i>in vitro</i>, producing 2-HMS. We also observe that when approximately twice the amount of S30 extract is added to an excess catechol solution, production of 2-HMS is increased approximately twofold. This suggests that the enzyme (rather than substrate) is the limiting component in catechol degradation by catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. This result corresponds with our hypothesis that the catechol 2,3-dioxygenase active site iron is reduced, rendering our enzyme inactive. The samples in Figure 3 were carried out in double distilled water. However, duplicates of the readings were measured in a buffer (20mM Tris pH 8.0. We do not observe a significant difference in 2-HMS production in samples containing buffer compared to samples containing double distilled water. | + | Figure 3 displays that catechol 2,3-dioxygenase can degrade catechol <i>in vitro</i>, producing 2-HMS. We also observe that when approximately twice the amount of S30 extract is added to an excess catechol solution, production of 2-HMS is increased approximately twofold. This suggests that the enzyme (rather than substrate) is the limiting component in catechol degradation by catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. This result corresponds with our hypothesis that the catechol 2,3-dioxygenase active site iron is reduced upon catalysis, rendering our enzyme inactive. The samples in Figure 3 were carried out in double distilled water. However, duplicates of the readings were measured in a buffer (20mM Tris pH 8.0). We do not observe a significant difference in 2-HMS production in samples containing buffer compared to samples containing double distilled water. |

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| Line 249: | Line 249: | ||

===<font color="white">Conclusion=== | ===<font color="white">Conclusion=== | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

| - | < | + | We have successfully show that our <i>E. coli</i> cells carrying the K118021 biobrick is capable of converting catechol into 2-HMS. Moreover, the reduction Figure 3 shows a reduction of 2-HMS concentration in the solution. It is more than likely, considering that 2-HMS can be metabolized by the cell, that the soluble metabolic machinery of <i>E. coli</i> is metabolizing 2-HMS into its breakdown products. This is a feature of the system that we intend to exploit in our remediation project. <br> |

| + | |||

| + | With this in mind, it is inefficient to utilize a single turnover enzyme such as catechol 2,3-dioxygenase in an industrial setting. We have identified a protein that will reduce the iron that is oxidized in the conversion of catechol to 2-HMS. The gene coding for this enzyme (<i>xylT</i>) codes for a ferredoxin protein, and is located on the same operon as <i>xylE</i> in <i>Pseudomonas putida</i><sup>1</sup></i>. <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We intend to introduce ferredoxin to our bioremediation project next year with the aim of increasing catechol 2,3-dioxygenase efficiency by allowing it to catalyze multiple turnovers of catechol to 2-HMS<br> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===<font color="white">References=== | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | <sup>1</sup>Polissi A., Harayama S. (1993) <b>In vivo reactivation of catechol 2,3-dioxygenase mediated by a chloroplast-type ferredoxin: a bacterial strategy to expand the substrate specificity of aromatic degradative pathways.</b>. <i>EMBO J.</i>, <b>12</b>(8); 3339-3347 | ||

=<font color="white">Compartmentalization Parts= | =<font color="white">Compartmentalization Parts= | ||

"

"