Team:MIT phage results

From 2010.igem.org

| (7 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:MIT_toggle">Overview</a></li> | <li><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:MIT_toggle">Overview</a></li> | ||

| + | <li><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:MIT_tmodel">Modelling</a></li> | ||

<li><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:MIT_tconst">Toggle Construction</a></li> | <li><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:MIT_tconst">Toggle Construction</a></li> | ||

| - | <li><a href=" | + | <li><a href="https://2010.igem.org/Team:MIT_composite">Characterization</a></li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</dd> | </dd> | ||

| Line 169: | Line 170: | ||

<b> Cross-linking </b><br> | <b> Cross-linking </b><br> | ||

| - | Over the course of the summer, we've found that taking AFM images is difficult and time-consuming. Our original plan was to take AFM images of cross-linking hyperphage | + | Over the course of the summer, we've found that taking AFM images is difficult and time-consuming. Our original plan was to take AFM images of cross-linking hyperphage. After repeated attempts and little success, we realized that we needed to have a fast way of debugging our system. |

| - | <br> | + | <br><br> |

To facilitate fast debugging, we designed a system that would couple the heterodimerization of GR1 and GR2 to a fluorescent output, via split GFP. | To facilitate fast debugging, we designed a system that would couple the heterodimerization of GR1 and GR2 to a fluorescent output, via split GFP. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| - | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/a/aa/SplitGFP.gif"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/ | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/a/aa/SplitGFP.gif"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/3/3e/SplitGFPdeux.gif" width=60%></a><br> |

| + | The animation above illustrates GR1 and GR2 binding together and allowing for the GFP to form and fluoresce. | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | <b>Conclusions and Future Directions </b><br> | ||

| + | We've created polyphage structures and sucessfully incorporated Fos and GR1 into the phage coat. These are the first steps towards accomplishing our vision of a living biomaterial. However, our accomplishments can be used by other researchers or iGEM teams for other goals. For example, if MIT iGEM 2011 wanted to make a living filter, they could use our system to display GR1 on polyphage. GR2 could be fused with a protein that binds an organic or inorganic substance of interest, e.g. gold. One can imagine that the protein would be able to bind the substance, and attach to the polyphage via the GR1/GR2 interaction. The bacteria could then be spun down slowly, taking the substance out of the solution. This example is just one of many possible extensions of the bacteriophage portion of the "living materials" project. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:56, 28 October 2010

hairy cells and polymerizing phage - results |

||||||||

|

Experimental Aims This summer, we pursued three main experimental aims:

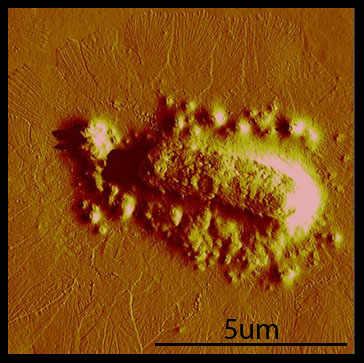

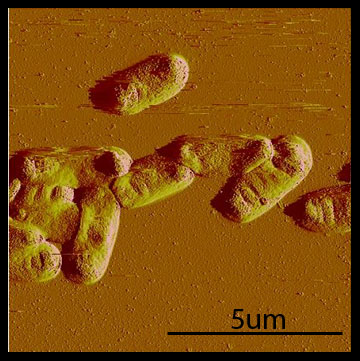

Polyphage formation Rakonjac and Model (1998) showed that in the absence of pIII, elongation of the phage proceeds without termination, and the assembling phage stay associated with the cells. We were able to reproduce this phenotype with cells transformed with the hyperphage phagemid. Cells that were transformed with the hyperphage phagemid show a dense mat of many long filaments extending from the cell.

In contrast, when we transformed with hyperphage and our pIII producing plasmid, BBa_K415138, we observed that the polyphage were absent.

Displaying Fusion Proteins In testing for the incorporation of our fusion into the phage coat, we chose to have M13K07 package our fusion instead of hyperphage. Testing with hyperphage would be difficult because the 100-fold reduction in infectivity (Rakonjac and Model, 1998) and the property of being tethered to the membrane introduce complications in the necessary amplification and purification steps. M13K07 and Hyperphage are equivalent in all other aspects, so M13K07 makes an ideal system for testing the ability of our fusions to be incorporated into the phage coat. We transformed cells with our fusions, infected them with the M13K07 helper phage, and purified the resulting amplified phage, then western blotted with HA and Myc antibodies. We did not induce cultures because our fusions were under control of R0065, a very leaky promoter, and we postulated that the basal level of expression would be enough for incorporation. In the western blot, we observed signals from p8-Fos* and p8-GR1. The other linkers may require some tuning of induction or additional troubleshooting before we observe incorporation.

Cross-linking Over the course of the summer, we've found that taking AFM images is difficult and time-consuming. Our original plan was to take AFM images of cross-linking hyperphage. After repeated attempts and little success, we realized that we needed to have a fast way of debugging our system. To facilitate fast debugging, we designed a system that would couple the heterodimerization of GR1 and GR2 to a fluorescent output, via split GFP.  The animation above illustrates GR1 and GR2 binding together and allowing for the GFP to form and fluoresce. Conclusions and Future Directions We've created polyphage structures and sucessfully incorporated Fos and GR1 into the phage coat. These are the first steps towards accomplishing our vision of a living biomaterial. However, our accomplishments can be used by other researchers or iGEM teams for other goals. For example, if MIT iGEM 2011 wanted to make a living filter, they could use our system to display GR1 on polyphage. GR2 could be fused with a protein that binds an organic or inorganic substance of interest, e.g. gold. One can imagine that the protein would be able to bind the substance, and attach to the polyphage via the GR1/GR2 interaction. The bacteria could then be spun down slowly, taking the substance out of the solution. This example is just one of many possible extensions of the bacteriophage portion of the "living materials" project.

← Construction

Context →

|

"

"

iGEM 2010

iGEM 2010