Team:Valencia/prion

From 2010.igem.org

(→References) |

|||

| (126 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | __NOTOC__ | ||

{{:Team:Valencia/head}} | {{:Team:Valencia/head}} | ||

<div id="HomeCenter"> | <div id="HomeCenter"> | ||

| - | =Regulating | + | {{Team:Valencia/to_project}} |

| + | <div id="Titulos"> | ||

| + | Regulating Mars temperature | ||

| + | using a prionic switch | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

==Prions== | ==Prions== | ||

| - | In 1982 Stanley B. Prusiner created the term “prion” (or proteinacius infectious particle) to name the exclusively proteic infectious agent responsible of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), a group of mammalian neurodegenerative disorders. According | + | In ([[#References |1982]]) Stanley B. Prusiner created the term “prion” (or proteinacius infectious particle) to name the exclusively proteic infectious agent responsible of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), a group of mammalian neurodegenerative disorders. According to the widely supported “protein-only” model, the prion mechanism of transmissibility arise from the ability of the prion form of the protein to promote the conformational change of the normal cellular form to the infectious prion forms ([[#References |Prusiner, 1998]]). This results in an autocatalytic process that is represented in the animation ''How the prion works?''. The infectious forms are mis-folded proteins that induce by polymerization the formation of an amyloid fold constituted by tightly packed beta sheets. These aggregates are insoluble fibrils that display resistance to proteolytic digestion and have affinity for aromatic dyes ([[#References |Cobb and Surewicz 2009]]). |

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div class="center"><div class="thumb tnone"><div class="thumbinner" style="width:502px;"> | ||

| + | <object classid="clsid:d27cdb6e-ae6d-11cf-96b8-444553540000" codebase="http://download.macromedia.com/pub/shockwave/cabs/flash/swflash.cab#version=9,0,0,0" width="500" height="375" id="Valencia_priones" align="middle"> | ||

| + | <param name="allowScriptAccess" value="sameDomain" /> | ||

| + | <param name="allowFullScreen" value="false" /> | ||

| + | <param name="movie" value=" | ||

| + | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/9/99/Valencia_priones.swf" /><param name="quality" value="high" /><param name="bgcolor" value="#ffffff" /> <embed src=" | ||

| + | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/9/99/Valencia_priones.swf" quality="high" bgcolor="#ffffff" width="500" height="375" name="baner_final_sin_btn" align="middle" allowScriptAccess="sameDomain" allowFullScreen="false" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" pluginspage="http://www.macromedia.com/go/getflashplayer" /> | ||

| + | </object> | ||

| + | <div class="thumbcaption"><b>How the prion works?</b> Schematic explanation on prionic systems.</div></div></div></div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

===Fungal prions=== | ===Fungal prions=== | ||

| - | + | Sixteen years ago, Reed Wickner ([[#References |1994]]) proposed the prion nature of Ure2, a protein involved in the nitrogen metabolism of the yeast ''Saccharomyces cerevisae'', to explain the unusual dominant and cytoplasmatic inheritance of the phenotype [''URE3''] first described by Cox ([[#References |1965]]). Other publications of a wide array of genetic and biochemical evidence have supported that the prionic behaviour is present in other yeast proteins such as Sup35, Rnq1 and Swi1 and in HET-s, a protein involved in the mechanism of genetic incompatibility between strains of ''Podospora anserina'' ([[#References |Shorter and Lindquist 2005]]). | |

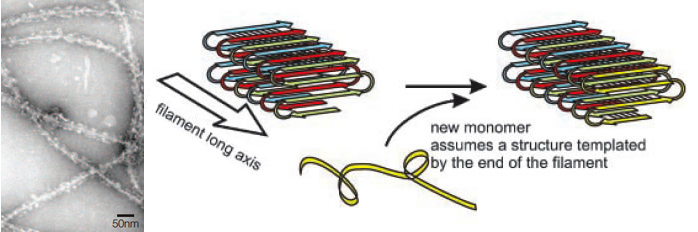

| - | These prions can produce amyloid-like fibrils similar to those associated with the mammalian prions. The molecular architecture of these amyloids have been studied using solid-state NMR spectroscopy and it has been found that the fibrils formed by Ure2p, Rnq1, and Sup35 share a common parallel and in-register β-structure (Fig.1) (Wickner et al. 2008). | + | These prions can produce amyloid-like fibrils similar to those associated with the mammalian prions. The molecular architecture of these amyloids have been studied using solid-state NMR spectroscopy and it has been found that the fibrils formed by Ure2p, Rnq1, and Sup35 share a common parallel and in-register β-structure (Fig.1) ([[#References |Wickner ''et al.'' 2008]]). However, these fungal prions have no sequence similarity with their mammalian counterparts ([[#References |Cobb and Surewicz 2009]]). Besides, they are not generally pathogenic and might have a beneficial role providing an evolutionary advantage to their hosts ([[#References |Halfmann ''et al.'' 2009]]). The prion domains of these fungal proteins have an exceptionally high content (~40%) of two polar amyloidogenic amino acids: glutamine and asparagine ([[#References |Cobb and Surewicz 2009]]). |

| + | [[Image:Valencia_amyloid.jpg|thumb|center|550px|'''Figure 1'''. Amyloid fibrils of fungal prions. At the left, electron microscopy of amyloid fibres formed by Sup35p (Shorter and Lindquist 2005). At the right, parallel in-register &beta-sheet model of yeast prion amyloids [URE3] (Ure2), [PSI+] (Ure2p) and [PIN+] (Rnq1). The hydrogen bonds of the main chain run parallel to the filament axis, while the main chains themselves are perpendicular to the filament axis (Wickner et al 2008).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fungal prions generally produce changes in phenotype that seem loss-of-function mutations, but with a non-Mendelian dominant inheritance. This abnormal genetic behaviour is due to the transference of the amyloidal fibers from mother cells to her daughters and mating partners. Once this prionic infective form is present, it catalyzes the change of conformation of all the proteins of the same type that were still in the functional non-prionic form. Therefore, this causes a dominant change in the phenotype that is perpetuated through generations ([[#References |Si ''et al.'' 2003]]). | ||

====Sup35p==== | ====Sup35p==== | ||

| - | [PSI+] is a non- | + | [''PSI<sup>+</sup>''] is a non-Mendelian trait of ''Saccharomyces cerevisae'' that supress nonsense codons. This phenotype is due to a self-replication conformation (prion state) of a protein encoded by the gene Sup35. This protein, Sup35p, is the yeast eukaryotic release factor 3 (eRF3) and constitutes the translation termination complex together with the protein Sup45p (eRF1). Sup35p releases the nascent polypeptide chain from the ribosome through GTP hydrolysis when Sup45p recognize a stop codon ([[#References |Shorter and Tyadmers 2005]]). |

| - | + | ||

| - | == | + | Sup35p is 685 amino acids long and has three distinct parts (Fig.2) ([[#References |Wickner et al 2008]]). The NH2-terminus (N) is termed the prion-forming domain (PrD) because plays a critical role in Sup35p’s changes in proteic conformation and it is responsible for its prion behaviour. This domain is 114 amino acids long and has a high content in glutamine and asparagine. The middle region (M) provides a solubilizing and/or spacing function. Finally, the COOH-terminus (C) is responsible for the translation-termination activity. |

| - | === | + | |

| - | The switch is formed by two different parts: the activator and the reporter. The activator part is a construction of two fragments: the NM domains of the protein Sup35, which confers to the protein the prionic activity, and the | + | [[Image:Valencia_prion_sup35.gif|thumb|center|400px|'''Figure 2'''. The prion domain of Sup35 is Q/N Rich and has the ability to propogate the corresponding prion in the absence of the rest of the molecule. Source: Wickner ''et al''. 2008.]] |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In [''PSI<sup>+</sup>''] cells, most Sup35p is insoluble and nonfunctional, causing an increase in the translational read-through of stop codons. This trait is heritable because Sup35p in the amyloid state as every prion influences new Sup35p to adopt the same conformation and passes from mother cell to daughter. In [''psi<sup>-</sup>''] cells, the translation-termination factor Sup35p is soluble and functional ([[#References |Li and Lindquist 2000]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Prionic switch== | ||

| + | ===Components=== | ||

| + | The switch is formed by two different parts: the activator and the reporter. The activator part is a construction of two fragments: the NM domains of the protein Sup35, which confers to the protein the prionic activity, and the GR<sup>526</sup> portion, which contains the DNA-binding and transcription-activation domains. The ligand-binding domain of the protein GR was eliminated, decoupling the response of the protein to the presence of glucocorticoids, and thus generating a constitutive transcription activation factor. The normal activity of this protein results in the activation of the genes preceded by the GRE (Glucocorticoid Response Element). When exposed to heat shock or other stress conditions, the NM domains start the prionic activity, eventually inhibiting the activation of transcription. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This part was amplified by using the primers indicated by [[#References |Li and Lindquist 2000]], together with the sequence recommended to use for the ligation protocol with the plasmid pSB1C3. Those primers are: | ||

| + | * Forward actagtagcggccgctgcagATGTCGGATTCAAAC | ||

| + | * Reverse tctagaagcggccgcgaattcTCCTGCAGTGGCTTG | ||

| + | (again, capital letters represent the region that pairs with the coding sequence of NMGR<sup>526</sup>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The second part consists of the GRE followed by the reporter gene. In our experiments, we used LacZ for this purpose. The amplification of this part could not be made because of some problems found when trying to find the sequence of the GRE. | ||

===Behaviour=== | ===Behaviour=== | ||

| - | ==Yeastworld== | + | Sup35p is a subunit of the translation termination complex. Its prionic nature has been proposed to have some effect on the stress response, as a possible mechanism to obtain modified genetic expression products. When the prionic conformation is activated, the termination of translation is less effective and thus new longer proteins form ([[#References |True and Lindquist 2000]]; [[#References |Tyedmers ''et al.'' 2008]]). When the sequence corresponding to the NM domains of Sup35p is fused to other gene, the protein resulting of this construction acquires the prionic behaviour ([[#References |True and Lindquist 2000]]). |

| + | |||

| + | On the other side, GR (Glucocorticoid Receptor) activates the transcription of genes preceded by GRE (Glucocorticoid Receptor Element) when steroid hormones are present ([[#References |Heizer ''et al.'' 2007]]). However, it becomes a constitutive transcription activator when it lacks its C terminal ligand-binding domain ([[#References |Schena and Yamamoto 1988]]). Because of the length of amino acids of the cut protein, this short version of GR is named GR<sup>526</sup>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[#References |Li and Lindquist 2000]] showed that the fused protein (NMGR<sup>526</sup>) is a functional constitutive transcription activator. In addition, when the prionic conformation is reached because of the presence of a certain stimulus, NMGR<sup>526</sup> is no longer capable of inducing the activation of the gene preceded by GRE. [[#References |Tyedmers ''et al.'' 2000]] checked the conditions that trigger the prionic conformation and they found that heat shock is a significantly relevant factor. The cells in which the prionic conformation is induced, the process is promoted in an autocatalytic manner and all the protein is found in the prionic conformation. The cells resulting show the phenotype [PSI+]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div class="center"><div class="thumb tnone"><div class="thumbinner" style="width:502px;"> | ||

| + | <object classid="clsid:d27cdb6e-ae6d-11cf-96b8-444553540000" codebase="http://download.macromedia.com/pub/shockwave/cabs/flash/swflash.cab#version=9,0,0,0" width="500" height="375" id="Valencia_priones" align="middle"> | ||

| + | <param name="allowScriptAccess" value="sameDomain" /> | ||

| + | <param name="allowFullScreen" value="false" /> | ||

| + | <param name="movie" value=" | ||

| + | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/2/28/Valencia_switch.swf" /><param name="quality" value="high" /><param name="bgcolor" value="#ffffff" /> <embed src=" | ||

| + | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/2/28/Valencia_switch.swf" quality="high" bgcolor="#ffffff" width="500" height="375" name="baner_final_sin_btn" align="middle" allowScriptAccess="sameDomain" allowFullScreen="false" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" pluginspage="http://www.macromedia.com/go/getflashplayer" /> | ||

| + | </object> | ||

| + | <div class="thumbcaption"><b>How the prionic switch works?</b> Explanation on how does the prionic switch fuction.</div></div></div></div> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | It is important to note that the rate of the change of conformation is not equal to zero even at optimal growth conditions, and that not all the cells become [PSI+]. The rate of spontaneous activation of the switch is thought to be around 10<sup>-6</sup> or 10<sup>-7</sup> ([[#References |Alberti ''et al.'' 2009]]). This process is promoted under heat stress ([[#References |Tyedmers ''et al.'' 2008]]), probably because of the important role of heat shock proteins like Hsp104 in the formation and maintenance of the amyloid fiber ([[#References |Halfmann ''et al.'' 2009]]). These approximate rates will have very important implications for the yeastworld model that we briefly describe in the following subsection, and with more detail in the [[Team:Valencia/modelling | Modelling]] section. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Introduction to the Yeastworld== | ||

| + | |||

| + | A model population of yeast containing the prionic switch growing under low temperatures would contain a pool of [psi -] (black) cells and a minimal amount of [PSI+] (white) cells. The high proportion of black yeasts will cause an increase of the planet mean temperature (as can be deduced by the [[Team:Valencia/WB | Microbial Albedo Recorder]] section of the project). As we explained in the section above, when the temperature is high enough, the prionic switch will tend to become activated. Then, there will be a much higher proportion of non-melanic [PSI+] cells. In addition to the underlying molecular tendency, the black cells will be selected against in this situation, because of the increasing of their inner temperature, in comparison to the white cells, that will provoke a reduction of their growth rate. The white cells, on the other hand, have an intrinsic protection against overheating due to their higher albedo. Thus, these cells will grow faster and become more and more abundant. The eventual high proportion of white cells will lead to an increase of the planetary albedo effect and a decrease of the mean temperature. This situation will become autoregulated and reach an equilibrium through several oscillatory cycles. The background and the dynamics of this process can be regarded with much more detail in the [[Team:Valencia/Modelling | Modelling]] section of the project, but the conclusion is quite remarkable: a pleasant equilibrium temperature of about 30ºC. | ||

==Experimental procedure== | ==Experimental procedure== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Plasmids and strains=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | As we mentioned in the [[Team:Valencia/prion#Components | Components]] subsection, the switch is formed by two different parts, which were handled independently. The prionic transcription activator was inserted into a multicopy (2μ) constitutive vector. The construct is called PG1-NMGR<sup>526</sup> ('''Fig 1:''' [[#References |Schena and Yamamoto 2008]]; see its card in [http://www.addgene.org/pgvec1?f=c&cmd=findpl&identifier=1122&attag=n Addgene]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The GRE+reporter portion was cloned into another multicopy vector, naming the construct pL2/GZ ('''Fig 2:'''; [[#References |Kimura ''et al.'' 2008]]; see its card in [http://www.addgene.org/pgvec1?f=c&cmd=findpl&identifier=1282&attag=n Addgene]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The plasmids were cloned into chemically competent BL21 Star ''E. coli'' cultures (read more about this bacterial strain in its [http://tools.invitrogen.com/content/sfs/manuals/oneshotbl21star_man.pdf Invitrogen] manual). The cultures were grown overnight at 37ºC and then the plasmids were isolated. Finally, yeast strain 5523 ([''psi<sup>-</sup>'']) was transformed using the lithium acetate protocol we describe in XXXXXX. The yeast strain 5523 has several auxotrophies (genotype ''ade1-14(UGA), trp1-289(UAG), his3Δ-200, ura3-52, leu2-3,112'') and the NM domains of Sup35 deleted from the background 74D-694 [''PSI<sup>+</sup>''] (read more about the obtaining of this strain in [[#References |True and Lindquist 2000]]). | ||

==Results== | ==Results== | ||

| + | |||

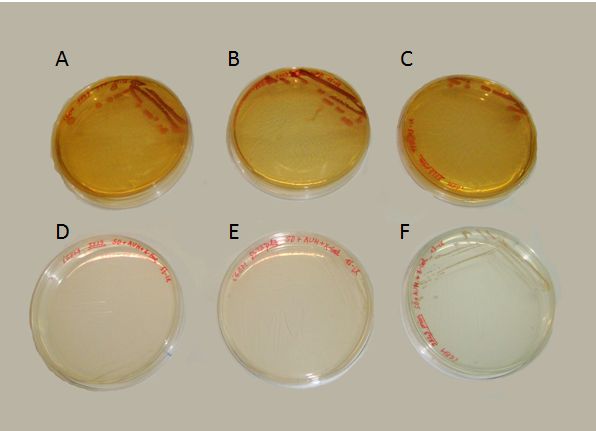

| + | We succeeded to transform the yeast strain 5523 with the two plasmids: PG1-NMGR<sup>526</sup> and pL2/GZ. In the Fig.3 we demonstrate the obtaining of this double transformation, where it can be seen that this strain was the only one that could grow on a selective medium, compared to others that did not possessed both plasmids. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Valencia_prions_dishes.jpg|thumb|center|500px|'''Figure 3'''. Transformation results. The three dishes at the top of the picture contain a rich (YPD) medium. The three dishes at the bottom contain a selective (SD+Ade+His+Ura) medium. The yeast strains growing on ech plate are (A and D) 5523 with no plamids, (B and E) 5523 with only the pL2/GZ plasmid and (C and F) 5523 with the complete prionic system. Because the plasmids confer the ability to overcome the triptophan (pG1-NMGR<sup>526</sup>) and leucine (pL2/GZ) auxotrophies, only the prionic system-containing yeasts could grow on the selective medium. The rich medium impose no restriction for the growth of the three strains.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Where growing in presence of X-gal, the proper substrate for the beta-galactosidase enzyme (our reporter gene for the behaviour of the prionic switch), we obtained both blue and white colonies. These colonies can be identified as the [''psi<sup>-</sup>''] and [''PSI<sup>+</sup>''] phenotypes. In contrast with the results of Li and Lindquist (2000) or Tyedmers ''et al.'' (2008), the proportion of white yeasts growing in our plates was unexpectedly high. Further optimization of the experimental manipulation would be needed for the proper characterization of the system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nevertheless, the presence of both blue and white colonies, in relation with the results explained in the [[Team:Valencia/WB | Microbial Albedo Recorder]] section, would be sufficient to recall the properties of the system at the population level. Then, the Yeastworld model (described above and, in more detail, in the [[Team:Valencia/Modeling | Modeling]] section) could depict the evolution and fate of a population of yeast containing the prionic system. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | *Alberti, S., Halfmann, R., King, O., Kapila, A., Lindquist, S. (2009). A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. ''Cell''. 137: 146-158. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Cobb, N.J., Surewicz, W. K. (2009). Prion diseases and their biochemical mechanisms. ''Biochemistry''. 48: 2574–2585. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Cox,B.S. (1965). A cytoplasmic suppressor of super-suppressor in yeast. ''Heredity''. 20: 505–521. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Halfmann, R., Alberti, S., Lindquist, S. (2009). Prions, protein homeostasis and phenotypic diversity. ''Trends in Cell Biology''. 20: 125-133. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Heitzer, M.D., Wolf, I.M., Sanchez, E.R., Witchel, S.F., DeFranco, D.B. (2007). Glucocorticoid receptor phisiology. ''Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord.''. 8: 321-330. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Li, L., Lindquist, S. (2000). Creating a protein-based element of inheritance. ''Science''. 287: 661-664. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Prusiner, S.B. (1982). Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 216: 136–144. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Prusiner, S.B. (1998). Prions. ''PNAS''. 95: 13363–13383. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Si, K., Lindquist, S. Kandel, E.R. (2003). A neuronal isoform of the Aplysia CPEB has prion-like properties. ''Cell''. 115: 879-891. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Schena, M., Yamamoto, K.R. (1988). Mammalian glucocorticoid receptor derivatives enhance transcription in yeast. ''Science''. 241: 965-967. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Shorter, J., Lindquist, S. (2005). Prions as adaptive conduits of memory and inheritance. ''Nature''. 6: 435-450. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *True, H.L., Lindquist, S. (2000). A yeast prion provides a mechanism for genetic variation and phenotypic diversity. ''Nature''. 407: 477-483. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Tyedmers, J., Madariaga, M.L., Lindquist, S. (2008). Prion switching in response to environmental stress. ''PLoS Biology''. 6: e294. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Wickner, R.B. (1994). [URE3] as an altered ''URE2'' protein: evidence for a prion analog in ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae''. ''Science''. 264: 566-569. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Wickner, R.B., Shewmaker, F., Kryndushkin, D., Edskes, H.K. (2008). Protein inheritance (prions) based on parallel in-register β-sheet amyloid structures. ''BioEssays''. 30: 955-964. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 21:16, 24 November 2010

Time goes by...

(El tiempo pasa...)

Follow us:

Our main sponsors:

Our institutions:

Visitor location:

» Home » The Project

Regulating Mars temperature using a prionic switch

Prions

In (1982) Stanley B. Prusiner created the term “prion” (or proteinacius infectious particle) to name the exclusively proteic infectious agent responsible of the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), a group of mammalian neurodegenerative disorders. According to the widely supported “protein-only” model, the prion mechanism of transmissibility arise from the ability of the prion form of the protein to promote the conformational change of the normal cellular form to the infectious prion forms (Prusiner, 1998). This results in an autocatalytic process that is represented in the animation How the prion works?. The infectious forms are mis-folded proteins that induce by polymerization the formation of an amyloid fold constituted by tightly packed beta sheets. These aggregates are insoluble fibrils that display resistance to proteolytic digestion and have affinity for aromatic dyes (Cobb and Surewicz 2009).

Fungal prions

Sixteen years ago, Reed Wickner (1994) proposed the prion nature of Ure2, a protein involved in the nitrogen metabolism of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisae, to explain the unusual dominant and cytoplasmatic inheritance of the phenotype [URE3] first described by Cox (1965). Other publications of a wide array of genetic and biochemical evidence have supported that the prionic behaviour is present in other yeast proteins such as Sup35, Rnq1 and Swi1 and in HET-s, a protein involved in the mechanism of genetic incompatibility between strains of Podospora anserina (Shorter and Lindquist 2005).

These prions can produce amyloid-like fibrils similar to those associated with the mammalian prions. The molecular architecture of these amyloids have been studied using solid-state NMR spectroscopy and it has been found that the fibrils formed by Ure2p, Rnq1, and Sup35 share a common parallel and in-register β-structure (Fig.1) (Wickner et al. 2008). However, these fungal prions have no sequence similarity with their mammalian counterparts (Cobb and Surewicz 2009). Besides, they are not generally pathogenic and might have a beneficial role providing an evolutionary advantage to their hosts (Halfmann et al. 2009). The prion domains of these fungal proteins have an exceptionally high content (~40%) of two polar amyloidogenic amino acids: glutamine and asparagine (Cobb and Surewicz 2009).

Fungal prions generally produce changes in phenotype that seem loss-of-function mutations, but with a non-Mendelian dominant inheritance. This abnormal genetic behaviour is due to the transference of the amyloidal fibers from mother cells to her daughters and mating partners. Once this prionic infective form is present, it catalyzes the change of conformation of all the proteins of the same type that were still in the functional non-prionic form. Therefore, this causes a dominant change in the phenotype that is perpetuated through generations (Si et al. 2003).

Sup35p

[PSI+] is a non-Mendelian trait of Saccharomyces cerevisae that supress nonsense codons. This phenotype is due to a self-replication conformation (prion state) of a protein encoded by the gene Sup35. This protein, Sup35p, is the yeast eukaryotic release factor 3 (eRF3) and constitutes the translation termination complex together with the protein Sup45p (eRF1). Sup35p releases the nascent polypeptide chain from the ribosome through GTP hydrolysis when Sup45p recognize a stop codon (Shorter and Tyadmers 2005).

Sup35p is 685 amino acids long and has three distinct parts (Fig.2) (Wickner et al 2008). The NH2-terminus (N) is termed the prion-forming domain (PrD) because plays a critical role in Sup35p’s changes in proteic conformation and it is responsible for its prion behaviour. This domain is 114 amino acids long and has a high content in glutamine and asparagine. The middle region (M) provides a solubilizing and/or spacing function. Finally, the COOH-terminus (C) is responsible for the translation-termination activity.

In [PSI+] cells, most Sup35p is insoluble and nonfunctional, causing an increase in the translational read-through of stop codons. This trait is heritable because Sup35p in the amyloid state as every prion influences new Sup35p to adopt the same conformation and passes from mother cell to daughter. In [psi-] cells, the translation-termination factor Sup35p is soluble and functional (Li and Lindquist 2000).

Prionic switch

Components

The switch is formed by two different parts: the activator and the reporter. The activator part is a construction of two fragments: the NM domains of the protein Sup35, which confers to the protein the prionic activity, and the GR526 portion, which contains the DNA-binding and transcription-activation domains. The ligand-binding domain of the protein GR was eliminated, decoupling the response of the protein to the presence of glucocorticoids, and thus generating a constitutive transcription activation factor. The normal activity of this protein results in the activation of the genes preceded by the GRE (Glucocorticoid Response Element). When exposed to heat shock or other stress conditions, the NM domains start the prionic activity, eventually inhibiting the activation of transcription.

This part was amplified by using the primers indicated by Li and Lindquist 2000, together with the sequence recommended to use for the ligation protocol with the plasmid pSB1C3. Those primers are:

- Forward actagtagcggccgctgcagATGTCGGATTCAAAC

- Reverse tctagaagcggccgcgaattcTCCTGCAGTGGCTTG

(again, capital letters represent the region that pairs with the coding sequence of NMGR526).

The second part consists of the GRE followed by the reporter gene. In our experiments, we used LacZ for this purpose. The amplification of this part could not be made because of some problems found when trying to find the sequence of the GRE.

Behaviour

Sup35p is a subunit of the translation termination complex. Its prionic nature has been proposed to have some effect on the stress response, as a possible mechanism to obtain modified genetic expression products. When the prionic conformation is activated, the termination of translation is less effective and thus new longer proteins form (True and Lindquist 2000; Tyedmers et al. 2008). When the sequence corresponding to the NM domains of Sup35p is fused to other gene, the protein resulting of this construction acquires the prionic behaviour (True and Lindquist 2000).

On the other side, GR (Glucocorticoid Receptor) activates the transcription of genes preceded by GRE (Glucocorticoid Receptor Element) when steroid hormones are present (Heizer et al. 2007). However, it becomes a constitutive transcription activator when it lacks its C terminal ligand-binding domain (Schena and Yamamoto 1988). Because of the length of amino acids of the cut protein, this short version of GR is named GR526.

Li and Lindquist 2000 showed that the fused protein (NMGR526) is a functional constitutive transcription activator. In addition, when the prionic conformation is reached because of the presence of a certain stimulus, NMGR526 is no longer capable of inducing the activation of the gene preceded by GRE. Tyedmers et al. 2000 checked the conditions that trigger the prionic conformation and they found that heat shock is a significantly relevant factor. The cells in which the prionic conformation is induced, the process is promoted in an autocatalytic manner and all the protein is found in the prionic conformation. The cells resulting show the phenotype [PSI+].

It is important to note that the rate of the change of conformation is not equal to zero even at optimal growth conditions, and that not all the cells become [PSI+]. The rate of spontaneous activation of the switch is thought to be around 10-6 or 10-7 (Alberti et al. 2009). This process is promoted under heat stress (Tyedmers et al. 2008), probably because of the important role of heat shock proteins like Hsp104 in the formation and maintenance of the amyloid fiber (Halfmann et al. 2009). These approximate rates will have very important implications for the yeastworld model that we briefly describe in the following subsection, and with more detail in the Modelling section.

Introduction to the Yeastworld

A model population of yeast containing the prionic switch growing under low temperatures would contain a pool of [psi -] (black) cells and a minimal amount of [PSI+] (white) cells. The high proportion of black yeasts will cause an increase of the planet mean temperature (as can be deduced by the Microbial Albedo Recorder section of the project). As we explained in the section above, when the temperature is high enough, the prionic switch will tend to become activated. Then, there will be a much higher proportion of non-melanic [PSI+] cells. In addition to the underlying molecular tendency, the black cells will be selected against in this situation, because of the increasing of their inner temperature, in comparison to the white cells, that will provoke a reduction of their growth rate. The white cells, on the other hand, have an intrinsic protection against overheating due to their higher albedo. Thus, these cells will grow faster and become more and more abundant. The eventual high proportion of white cells will lead to an increase of the planetary albedo effect and a decrease of the mean temperature. This situation will become autoregulated and reach an equilibrium through several oscillatory cycles. The background and the dynamics of this process can be regarded with much more detail in the Modelling section of the project, but the conclusion is quite remarkable: a pleasant equilibrium temperature of about 30ºC.

Experimental procedure

Plasmids and strains

As we mentioned in the Components subsection, the switch is formed by two different parts, which were handled independently. The prionic transcription activator was inserted into a multicopy (2μ) constitutive vector. The construct is called PG1-NMGR526 (Fig 1: Schena and Yamamoto 2008; see its card in [http://www.addgene.org/pgvec1?f=c&cmd=findpl&identifier=1122&attag=n Addgene]).

The GRE+reporter portion was cloned into another multicopy vector, naming the construct pL2/GZ (Fig 2:; Kimura et al. 2008; see its card in [http://www.addgene.org/pgvec1?f=c&cmd=findpl&identifier=1282&attag=n Addgene]).

The plasmids were cloned into chemically competent BL21 Star E. coli cultures (read more about this bacterial strain in its [http://tools.invitrogen.com/content/sfs/manuals/oneshotbl21star_man.pdf Invitrogen] manual). The cultures were grown overnight at 37ºC and then the plasmids were isolated. Finally, yeast strain 5523 ([psi-]) was transformed using the lithium acetate protocol we describe in XXXXXX. The yeast strain 5523 has several auxotrophies (genotype ade1-14(UGA), trp1-289(UAG), his3Δ-200, ura3-52, leu2-3,112) and the NM domains of Sup35 deleted from the background 74D-694 [PSI+] (read more about the obtaining of this strain in True and Lindquist 2000).

Results

We succeeded to transform the yeast strain 5523 with the two plasmids: PG1-NMGR526 and pL2/GZ. In the Fig.3 we demonstrate the obtaining of this double transformation, where it can be seen that this strain was the only one that could grow on a selective medium, compared to others that did not possessed both plasmids.

Where growing in presence of X-gal, the proper substrate for the beta-galactosidase enzyme (our reporter gene for the behaviour of the prionic switch), we obtained both blue and white colonies. These colonies can be identified as the [psi-] and [PSI+] phenotypes. In contrast with the results of Li and Lindquist (2000) or Tyedmers et al. (2008), the proportion of white yeasts growing in our plates was unexpectedly high. Further optimization of the experimental manipulation would be needed for the proper characterization of the system.

Nevertheless, the presence of both blue and white colonies, in relation with the results explained in the Microbial Albedo Recorder section, would be sufficient to recall the properties of the system at the population level. Then, the Yeastworld model (described above and, in more detail, in the Modeling section) could depict the evolution and fate of a population of yeast containing the prionic system.

References

- Alberti, S., Halfmann, R., King, O., Kapila, A., Lindquist, S. (2009). A systematic survey identifies prions and illuminates sequence features of prionogenic proteins. Cell. 137: 146-158.

- Cobb, N.J., Surewicz, W. K. (2009). Prion diseases and their biochemical mechanisms. Biochemistry. 48: 2574–2585.

- Cox,B.S. (1965). A cytoplasmic suppressor of super-suppressor in yeast. Heredity. 20: 505–521.

- Halfmann, R., Alberti, S., Lindquist, S. (2009). Prions, protein homeostasis and phenotypic diversity. Trends in Cell Biology. 20: 125-133.

- Heitzer, M.D., Wolf, I.M., Sanchez, E.R., Witchel, S.F., DeFranco, D.B. (2007). Glucocorticoid receptor phisiology. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord.. 8: 321-330.

- Li, L., Lindquist, S. (2000). Creating a protein-based element of inheritance. Science. 287: 661-664.

- Prusiner, S.B. (1982). Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 216: 136–144.

- Prusiner, S.B. (1998). Prions. PNAS. 95: 13363–13383.

- Si, K., Lindquist, S. Kandel, E.R. (2003). A neuronal isoform of the Aplysia CPEB has prion-like properties. Cell. 115: 879-891.

- Schena, M., Yamamoto, K.R. (1988). Mammalian glucocorticoid receptor derivatives enhance transcription in yeast. Science. 241: 965-967.

- Shorter, J., Lindquist, S. (2005). Prions as adaptive conduits of memory and inheritance. Nature. 6: 435-450.

- True, H.L., Lindquist, S. (2000). A yeast prion provides a mechanism for genetic variation and phenotypic diversity. Nature. 407: 477-483.

- Tyedmers, J., Madariaga, M.L., Lindquist, S. (2008). Prion switching in response to environmental stress. PLoS Biology. 6: e294.

- Wickner, R.B. (1994). [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 264: 566-569.

- Wickner, R.B., Shewmaker, F., Kryndushkin, D., Edskes, H.K. (2008). Protein inheritance (prions) based on parallel in-register β-sheet amyloid structures. BioEssays. 30: 955-964.

"

"