Team:Caltech/Human Impact

From 2010.igem.org

Paul.nguyen (Talk | contribs) |

Paul.nguyen (Talk | contribs) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

Theoretically, a competitor should own any component submitted to the contest inasmuch as the competitor contributed to the novelty of the component in a major way. Whole organisms/subspecies/strains should not be owned if the competitor did not contribute to the differentiation of the species; isolated naturally-occurring genes should not be owned. Ownership of a biological organism or part cannot be claimed if the competitor did not partake in its creation – for example, the chemist who first isolates gold does not own all gold, but does own the isolation if it is a novel one, and this process would then be patentable. Following this logic it is also clear that isolating a gene does not lead to its patentability. | Theoretically, a competitor should own any component submitted to the contest inasmuch as the competitor contributed to the novelty of the component in a major way. Whole organisms/subspecies/strains should not be owned if the competitor did not contribute to the differentiation of the species; isolated naturally-occurring genes should not be owned. Ownership of a biological organism or part cannot be claimed if the competitor did not partake in its creation – for example, the chemist who first isolates gold does not own all gold, but does own the isolation if it is a novel one, and this process would then be patentable. Following this logic it is also clear that isolating a gene does not lead to its patentability. | ||

| - | On 29 March 2010, US District Court Judge Robert Sweet ruled that "products of nature do not constitute patentable subject matter unless modified enough to be a fundamentally new product," invalidating many gene patents in the process[25]. Previously, roughly 40,000 United States patents exist that correspond to about 2,000 human genes, or 20 percent of the human genome. It is still too soon to know how this issue will fall in the appeals courts, but it shows the realization by the courts that genes are information, not chemicals. It also suggests that scientists and engineers may soon be able to utilize all the genes in the quickly-growing GenBank databases free of worry from IP infringement. | + | On 29 March 2010, US District Court Judge Robert Sweet ruled that "products of nature do not constitute patentable subject matter unless modified enough to be a fundamentally new product," invalidating many gene patents in the process [25]. Previously, roughly 40,000 United States patents exist that correspond to about 2,000 human genes, or 20 percent of the human genome. It is still too soon to know how this issue will fall in the appeals courts, but it shows the realization by the courts that genes are information, not chemicals. It also suggests that scientists and engineers may soon be able to utilize all the genes in the quickly-growing GenBank databases free of worry from IP infringement. |

Similarly, modifications to biological organisms or parts need to be carefully considered for originality. The rewriting of a book, superficially changing names of characters, locations, etc is not copyrightable in its own right, although the new names and characters could be considered the work of the new “author”; forming a DNA sequence degenerate to an already existing one, then, should not lead to a copyright. Modifying a car engine design does not lead to the patentability of all cars with that engine design, only that of the engine design proper; thus, whole organisms with novel genes should not be patentable in their entirety; the significant changes made, however, are the property of the person responsible and are patentable. | Similarly, modifications to biological organisms or parts need to be carefully considered for originality. The rewriting of a book, superficially changing names of characters, locations, etc is not copyrightable in its own right, although the new names and characters could be considered the work of the new “author”; forming a DNA sequence degenerate to an already existing one, then, should not lead to a copyright. Modifying a car engine design does not lead to the patentability of all cars with that engine design, only that of the engine design proper; thus, whole organisms with novel genes should not be patentable in their entirety; the significant changes made, however, are the property of the person responsible and are patentable. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

=== What does iGEM or MIT own from this competition? in what capacity? === | === What does iGEM or MIT own from this competition? in what capacity? === | ||

| - | According to the | + | According to the BioBrick™ Public Agreement, neither iGEM nor MIT own the material submitted to the competition. The competition and the university are simply the venue for displaying the bioengineering projects. Any possible ownership does not fall on iGEM or MIT; parts, documentation, and presented materials are all property of the competitors participating in the iGEM competition. |

=== What does the BioBrick™ Foundation own? in what capacity? === | === What does the BioBrick™ Foundation own? in what capacity? === | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

The university may lay claim to objects produced within the context of the university as agreed upon by students when they have matriculated and accepted working positions. For example, a university may own all developments funded by the university, while individual discoverers or developers may receive royalties on profits. | The university may lay claim to objects produced within the context of the university as agreed upon by students when they have matriculated and accepted working positions. For example, a university may own all developments funded by the university, while individual discoverers or developers may receive royalties on profits. | ||

| - | === If another team patents a process for their project, and submit | + | === If another team patents a process for their project, and submit its BioBrick™ parts to the Registry, can I use those bricks in my project? === |

Certainly! The team can only patent a novel process it develops. It cannot both patent a brick and send it in to the Registry to be distributed. If a team uses a patented sequence in its project, you will need special permission from the patent-holder to obtain and use the sequence in your project, but in this case, the DNA would not be available in the Registry. | Certainly! The team can only patent a novel process it develops. It cannot both patent a brick and send it in to the Registry to be distributed. If a team uses a patented sequence in its project, you will need special permission from the patent-holder to obtain and use the sequence in your project, but in this case, the DNA would not be available in the Registry. | ||

| - | The iGEM requirement that | + | The iGEM requirement that BioBrick™ parts must be submitted to the Registry to be eligible for judging incentivizes the submission of new parts into the public domain, allowing other teams to build on them and create even better systems. This prevents the universal application of patents to all iGEM projects and maintains the open nature of the Registry. In this way, iGEM projects and entrepreneurial efforts can coexist peacefully, and indeed, fruitfully. Teams contribute to the overall body of available genetic parts, and can protect their innovation by patenting their unique procedure or a few parts specific to their application. |

=== How does this apply to 3D printing, for example? === | === How does this apply to 3D printing, for example? === | ||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

===The Bottom Line:=== | ===The Bottom Line:=== | ||

| - | We hope that our example will become the accepted means for | + | We hope that our example will become the accepted means for teams to protect their innovation while still making their parts available for use by others. The Registry is predicated upon principles of generosity and openness, and its success is dependent on the willingness of teams to both utilize its resources and submit their own additions. However, there is no reason why this philosophy should be incompatible with entrepreneurial development, as with any other open-source system. |

| + | |||

| + | We believe that the BioBrick™ Public Agreement is a good step in the direction of a sustainable Registry and we hope future teams wishing to protect their work will consider doing so in a way that does not inhibit future iGEM innovation. That is, we hope they avoid patenting primary gene sequences whenever possible, and instead submit as many high-quality bricks to the Registry as possible. Rather, teams should work to patent their particularly innovative process. If a gene patent seems unavoidable, we encourage them to grant a free license to the Registry to distribute their brick for purely nonprofit research purposes. | ||

| | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:33, 27 October 2010

|

People

|

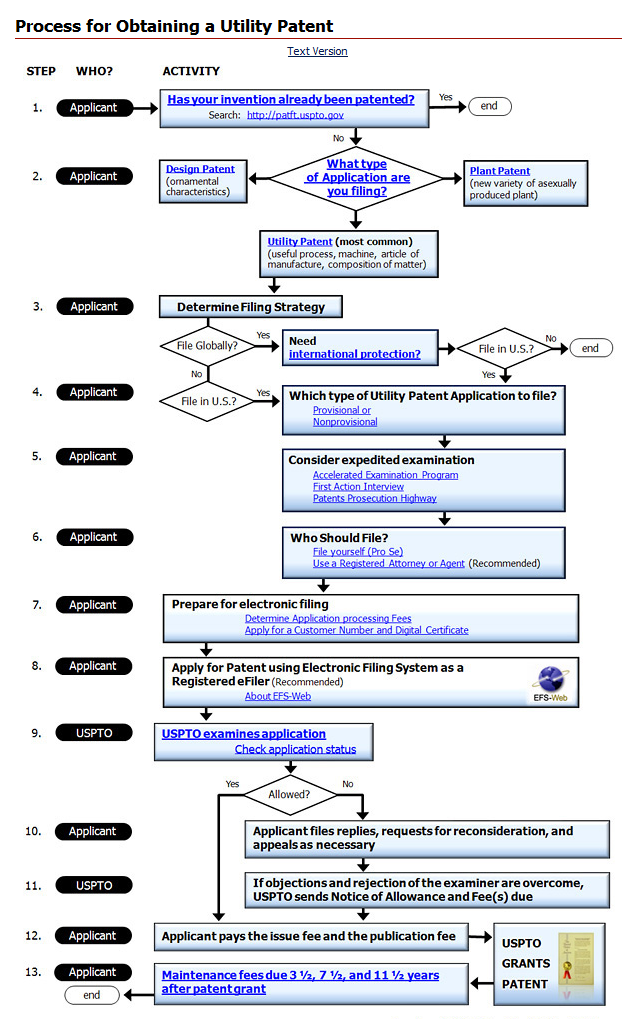

Human ImpactWith any new development in technology, there coincides a need to appropriate the new object in the established context. We intend to delineate any major questions about that process by pointing towards answers to these common concerns listed below, and describe how entrepreneurial and open-source work can coexist. Feel free to jump to the Bottom Line. What are the potentially proprietary components of a biologically engineered project?Theoretically, a competitor should own any component submitted to the contest inasmuch as the competitor contributed to the novelty of the component in a major way. Whole organisms/subspecies/strains should not be owned if the competitor did not contribute to the differentiation of the species; isolated naturally-occurring genes should not be owned. Ownership of a biological organism or part cannot be claimed if the competitor did not partake in its creation – for example, the chemist who first isolates gold does not own all gold, but does own the isolation if it is a novel one, and this process would then be patentable. Following this logic it is also clear that isolating a gene does not lead to its patentability. On 29 March 2010, US District Court Judge Robert Sweet ruled that "products of nature do not constitute patentable subject matter unless modified enough to be a fundamentally new product," invalidating many gene patents in the process [25]. Previously, roughly 40,000 United States patents exist that correspond to about 2,000 human genes, or 20 percent of the human genome. It is still too soon to know how this issue will fall in the appeals courts, but it shows the realization by the courts that genes are information, not chemicals. It also suggests that scientists and engineers may soon be able to utilize all the genes in the quickly-growing GenBank databases free of worry from IP infringement. Similarly, modifications to biological organisms or parts need to be carefully considered for originality. The rewriting of a book, superficially changing names of characters, locations, etc is not copyrightable in its own right, although the new names and characters could be considered the work of the new “author”; forming a DNA sequence degenerate to an already existing one, then, should not lead to a copyright. Modifying a car engine design does not lead to the patentability of all cars with that engine design, only that of the engine design proper; thus, whole organisms with novel genes should not be patentable in their entirety; the significant changes made, however, are the property of the person responsible and are patentable. What are the expected effects of proprietary work on the public nature of iGEM? What sort of interface can we expect in general between private and public property with respect to biological systems?Private use of public property may lead to more novel ideas because of larger incentive and identification with private projects. Take Unix/Linux, for instance: private companies for years have used Unix/Linux, an open-source, public platform, to develop proprietary software. The privatization of development has resulted in refined, successful products such as the Red Hat and Android operating systems, yet the development of those and related software products does not infringe upon the original public nature of Unix/Linux. For iGEM in particular, the private development of biological systems will not affect the public nature of iGEM or the Registry – the people developing those systems have full right to release their product to the Registry (thus making the parts public) or keep them for their continued private use. The use of parts already in the Registry is equivalent to taking the code base of Linux to form a novel operating system: although the code base is public domain, individual novel contributions are counted as personal property and thus the incentive for private development remains intact. What is a patent?A patent is an establishment of exclusive rights between an inventor or his assignee for a finite period of time in exchange for public disclosure of an invention or innovation. Functionally, a patent gives an inventor the time to profit off of his invention for a time period wherein his competitors cannot copy or use the patented idea legally without an arrangement with said inventor. Additionally, a patent serves as a record of new technologies invented by others, such that a person wanting to develop a product and compete in a market knows what has been invented, what ideas/technologies are currently in place, and where new inventions can be made. How would one go about obtaining a patent?The process of obtaining a patent can be found on the [http://www.uspto.gov/patents/process/index.jsp USPTO website]. Further questions about patents are answered on the [http://www.uspto.gov/faq/patents.jsp USPTO FAQ]. What is a copyright?Copyright is a form of protection for original works of authorship fixed in a tangible medium of expression. Copyright formally establishes the ownership between authors and both published and unpublished works. How would one go about obtaining a copyright?The process of obtaining a copyright can be found [http://www.copyright.gov/faq.html here]. What does iGEM or MIT own from this competition? in what capacity?According to the BioBrick™ Public Agreement, neither iGEM nor MIT own the material submitted to the competition. The competition and the university are simply the venue for displaying the bioengineering projects. Any possible ownership does not fall on iGEM or MIT; parts, documentation, and presented materials are all property of the competitors participating in the iGEM competition. What does the BioBrick™ Foundation own? in what capacity?The BioBrick™ Foundation is a nonprofit organization storing open source material. It does not privately own any of the BioBrick™ parts. All of the BioBrick™ parts are available for anyone to use. A draft of a public agreement has been written to help define concerns about BioBrick™ submissions. See the [http://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/50999/BPA_draft_v1a.pdf?sequence=1 BioBrick™ Public Agreement draft] (PDF). What does the university own? in what capacity?The university may lay claim to objects produced within the context of the university as agreed upon by students when they have matriculated and accepted working positions. For example, a university may own all developments funded by the university, while individual discoverers or developers may receive royalties on profits. If another team patents a process for their project, and submit its BioBrick™ parts to the Registry, can I use those bricks in my project?Certainly! The team can only patent a novel process it develops. It cannot both patent a brick and send it in to the Registry to be distributed. If a team uses a patented sequence in its project, you will need special permission from the patent-holder to obtain and use the sequence in your project, but in this case, the DNA would not be available in the Registry. The iGEM requirement that BioBrick™ parts must be submitted to the Registry to be eligible for judging incentivizes the submission of new parts into the public domain, allowing other teams to build on them and create even better systems. This prevents the universal application of patents to all iGEM projects and maintains the open nature of the Registry. In this way, iGEM projects and entrepreneurial efforts can coexist peacefully, and indeed, fruitfully. Teams contribute to the overall body of available genetic parts, and can protect their innovation by patenting their unique procedure or a few parts specific to their application. How does this apply to 3D printing, for example?In our case, Caltech owns the IP for our project, since the entirety of the work was funded by the institute. However, each team member is eligible to receive a fraction of any profits derived from the technology that Caltech receives. However, we are submitting all the parts we produced to the Registry, meaning any other team can build on them. The only restriction is on the 3D printing procedure itself, which is protected by provisional patent: CIT 5637-P. The Bottom Line:We hope that our example will become the accepted means for teams to protect their innovation while still making their parts available for use by others. The Registry is predicated upon principles of generosity and openness, and its success is dependent on the willingness of teams to both utilize its resources and submit their own additions. However, there is no reason why this philosophy should be incompatible with entrepreneurial development, as with any other open-source system. We believe that the BioBrick™ Public Agreement is a good step in the direction of a sustainable Registry and we hope future teams wishing to protect their work will consider doing so in a way that does not inhibit future iGEM innovation. That is, we hope they avoid patenting primary gene sequences whenever possible, and instead submit as many high-quality bricks to the Registry as possible. Rather, teams should work to patent their particularly innovative process. If a gene patent seems unavoidable, we encourage them to grant a free license to the Registry to distribute their brick for purely nonprofit research purposes.

|

"

"