Team:Brown/Obstacles learning

From 2010.igem.org

What We've Learned

We've come up against many obstacles this summer and learned a lot: as students, as scientists, and as people. Here are some of the challenges we faced and the lessons we learned from them:

The Team

Brown's team structure is unique to the iGEM community. Unlike the majority of teams, we are completely independent undergraduate students. We do not have a PI or graduate students to continually instruct us in what to do, nor a lab that has years of data and background on a given project. All students on the team are doing iGEM for the first time. Our advisors are available to answer specific questions, help us solve critical laboratory issues, and suggest things to look into, but the entirety of the project idea creation, evaluation, and execution is our own. Although the lack of external structure was at times frustrating, it was immeasurably valuable in teaching us independence, prioritization, and organization.

Our team is also composed purely of first- and second-year students. This means that within the six-person team, there was a wide range of background knowledge. With such a variance in the level of knowledge and practice, it was often difficult and time-consuming to bridge gaps between members. However, in working through this, we learned to be not just peers, but peer educators, and in the end we all emerged as a cohesive team with a much closer level of understanding.

The Lab

The Brown iGEM lab is maintained entirely by the undergraduate team. It is a former prep-lab in the basement of our BioMed building. The lab space is very limited, and does not have the capacity for BSL2 work (we had to seek temporary BSL2 space elsewhere). All our materials are ordered and maintained by the team. We make our own stocks, pour our own plates, deal with waste, manage a budget, and do everything else associated with the upkeep of a laboratory space that often take place behind the scenes in larger labs. Through these challenges, we learned not just how to work in a laboratory, but how to run one from the bottom up.

The challenge of keeping everything sterile and clean in such a small space meant that contamination was an issue in many of our procedures. At one point, progress on some procedures was stalled for a week while we worked out the source of yeast contamination in our plates. At another point, our XL1Blue stocks were somehow contaminated with tetracycline resistance from an unknown source. Having to repeat so many failed procedures slowed our progress, but also allowed us to learn the protocols much better.

The Projects

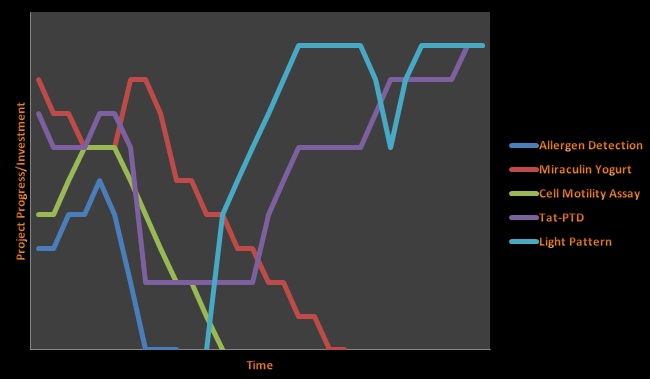

We began the summer with four projects in mind: a "Cell Motility" project, an "Allergen Detection Device," and a "Miraculin" project, as described below. The fourth project was the Tat-PTD project, which, as documented on its own page, went through a drastic evolution. The team decided to pursue the Light Pattern Controlled Circuit after a month of summer had almost passed, when it became evident that the Allergen Detection Device was likely no longer worth pursuing and other projects were having technical difficulties.

Dropped projects:

Motility

One of the projects we considered was a novel way of profiling gene expression through a bacterial motility assay. We obtained strains of E. coli with motA and motB deletions, preventing them from producing key protein components of the flagella rotary motor. Our idea was to rescue cell motility with a construct that also contained a gene of interest. Since the gene of interest would be in frame with the motA/motB construct and under the same promoter, we would use cell motility as a reporter for the gene of interest.

This would allow us to quickly characterize the synthesis rate of any gene of interest indirectly, by comparing the rescued motility speed with that of other speeds that correspond to known synthesis rates. This method of expression profiling would allow for quick visual determination of gene expression, and would also function as a simple selection mechanism (i.e. one could iteratively select for the level of selection desired over several generations of selection)

We received motA/motB mutant cells and the beginning of the summer and began to quantify motility through simple soft-agar stabs. We began a joint project with the biomedical engineering department at Brown and obtained microfluidic chambers for use in minimizing brownian motion and encouraging motility in a single direction. We also began work on optical algorithms for tracking of single cells over time, to quantify motion.

In the end we had concerns about sensitivities related to our assay; we were not sure that the levels of rescue would be continuous enough to function acceptably as a method of gene expression profiling, and we ultimately decided to devote our time and resources to the pursuit of alternative projects, which at the time appeared more promising.

Allergen Detection

One of the projects we initially pursued at the beginning of summer focused on designing an Allergen Detection Device for the peanut allergens araH1 and araH2. We focused our efforts into developing a prototype lateral flow assay that we could apply our project to. However, in developing this assay, we discovered that a very similar peanut allergen detection flow assay was involved in a recent heated intellectual property debate between two companies. Not wanting to infringe, we abandoned the idea in favor of our other functional projects at the time.

Miraculin Yogurt

One of our main projects at the beginning of the summer was a yogurt bacterium that would express miraculin. Miraculin is a transient taste-modifying protein that causes the tongue to pick up sour flavors as sweet. We reasoned that this would be useful and practical for a huge number of reasons.

However, when it came to the practical construction of such an organism, we began to hit roadblocks (as past teams have when dealing with Lactobacillus). It took us many attempts to find a suitable plasmid for transforming into yogurt-producing Lactobacilli, and the first few times we did, the iGEM teams or research groups that we contacted no longer had the DNA to send to us. Because of our limited budget and time constraints, we decided against ordering a custom-synthesized cassette. When we finally obtained the plasmid, we encountered difficulties in securing a 30C incubator and growing the lactobacilli in a microaerobic environment. Generation time for these organisms is longer than E.coli, so it took us a while to see results. When we finally reached a point where we were ready to perform a test transformation, difficulties in electroporation convinced the team that we should abandon the project in favor of our alternate ideas.

This idea is a promising one, and it may be pursued as an independent study after the Jamboree is over.

Additional Insight

In having to design our own experiments from the bottom up, we all learned a lot about protocols and experimental design. We learned how to run a lab, not just work in one. We learned how to work as a team, how to be think outside the box, and most importantly how to deal with failure.

Compared with our academic courses, our other research experiences, etc, this is not the level of success we are used to, nor one we expected. But this is also not the average challenge we face. We are unique in the iGEM world, and in the world of undergraduate research at Brown. Our pride in our work this summer was not the number of papers we published or the number of parts we contributed, but rather in how we have learned keep moving forward when facing endless difficulties. We are looking forward to sharing our experience with peers at the iGEM Jamboree, and cannot stress how valuable the past few months have been.

"

"