Team:Newcastle/E-Science

From 2010.igem.org

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Contents |

An e-Science Approach to Synthetic Biology

Motivation:

| Synthetic Biology is the engineering of biological entities to perform novel and desirable functions. Synthetic biologists already make use of computational resources to a large extent which can be seen by the software tools such as CLONEQC, Biskit and Internet based repositories such as the MIT Biobrick library at http://partsregistry.org/Main_Page. In both Systems and Synthetic Biology analysis consists of researchers taking the outputs from some software and feeding it to the inputs of other software. This pipeline or workflow can be computerised by using software such as [http://www.taverna.org.uk/ Taverna]. Research into the application of computerised workflows to Synthetic Biology has revealed the paucity of published material in this area. Therefore, this has been identified as an opportunity for research and possible development of tools, which could greatly enhance methodologies and workflows in Synthetic Biology. We show how an e-Science approach, i.e. the utilisation of advanced computing resources and technologies to support scientists, benefits the Synthetic Biology engineering process. We further propose a development life-cycle and show how this approach can improve the design of synthetic biological entities. |

Introduction:

| Aim:

The aim of this project was to investigate the application of e-Science approaches in Synthetic Biology, particularly workflows. | |

Objectives:

|

Synthetic Biology:

| Chopra defines Syntehtic Biology as a field that involves the synthesis of novel biological systems which are not generally found in nature (Chopra and Kamma, 2006). |

Engineering Principles:

| Two design approaches to Synthetic biology are emerging, namely top-down and bottom up.

The top-down approach starts with an overview of a system. The system is studied and iteratively broken into modules until the complete system can be described in terms of minimal elements. In the bottom-up approach design starts with minimal elements that, according to certain rules, can fit together like Lego c bricks (http://lego.com) until a complete system is built (Heinemann and Panke, 2006). Synthetic biologists are adopting principles from established fields of engineering to increase tractability and speed of design (Andrianantoandro et al., 2006). We define Synthetic Biology as: Synthetic Biology is the engineering of biological systems to perform desirable and predictable functions. |

Modelling languages:

| Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) was developed to represent biochemical reaction networks in a way that can be used by different software systems to exchange models ().

CellML is a mark-up language used to store and exchange computer based mathematical models. Originally it was intended for the description of biological models, but it has been adopted by several other fields of study. Both CellML and SBML are based on the XML (Hucka, 2003; Cuellar et al., 2003). The main difference between SMBL and CellML is that in CellML the underlying mathematics of cellular models are described in a very general way. |

Virtual Parts:

| Cooling et al. (2010) introduce the concept of Standard Virtual Biological Parts (further on referred to as virtual parts). Virtual parts are mathematical models used to represent biological parts that can be combined to inform system design.

The use of virtual parts, however, goes beyond just the representation of biological parts. The virtual parts can also be used to represent bioenvironmental elements which are intracellular events occurring in cells or chassis. These bioenvironmental elements become interfacing parts that act as "glue" for the aggregation of the standard biological parts. We refer to the standard biological parts as physical parts and the interfacing parts as non-physical parts. |

Development Life Cycle:

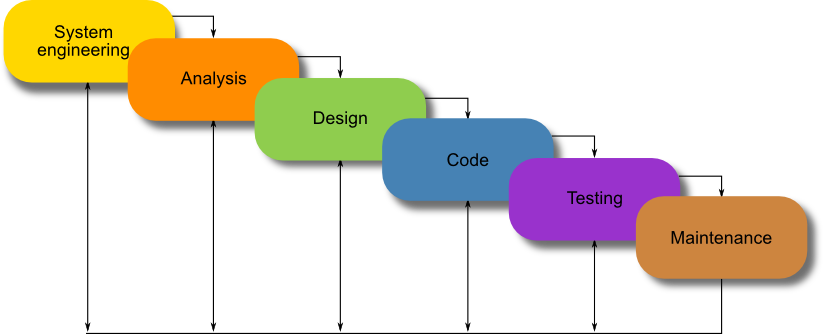

Another concept, that can be borrowed from software engineering, is the software development life cycle (SDLC). We used, as a basis, what is known as the classic life-cycle paradigm or waterfall model, see Figure 2.

e-Science:

| "The term 'e-Science' denotes the systematic development of research methods that exploit advanced computational thinking"

Professor Malcolm Atkinson, eScience Envoy e-Science is an enabling concept. It aims to allow the sharing of resources required in science across administrative borders. Sharing is accomplished by tapping into techniques such as cloud and grid computing.

|

Web Services:

| Web services are set apart from other types of services by the communications protocol they use. To be part of what is known as the Web, using HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is a prerequisite.

Web services, regardless of the architecture chosen, enable programmatic access to on-line resources and therefore more and more services are developed and become available on-line. SOAP web services: The Simple Object Access Protocol, or SOAP as it is popularly known was originally designed to be a RPC (Remote Procedure Call) protocol using HTTP as the transport protocol. It was later extended to allow for other transport protocols such as the Simple Mail Transport Protocol (SMTP) (Kennard and Stiver, 2000). SOAP is a packaging protocol for sharing messages between applications (Snell, 2001). RESTful web services: Roy Fielding described REST, Representational State Transfer, a software architectural style (Fielding and Fielding, 2000). REST uses the WWW as a starting point. Fielding refers to the WWW as the Null Style. As such it is an ideal architecture for web services. |

Workflows:

| A workflow can be described as a sequence of connected steps or work activities that are followed to produce a required outcome. The sequence and the ways the steps impact on each other are regulated by a set of rules (DiCaterino et al., 1997 ).

The processing of the information drawn from all the distributed sources can be accomplished using workflows. To manage the complex and heterogenous nature of such a distributed environment, scientist have turned to computerised workflows. |

Methods:

The Synthetic Biology Development Lifecycle

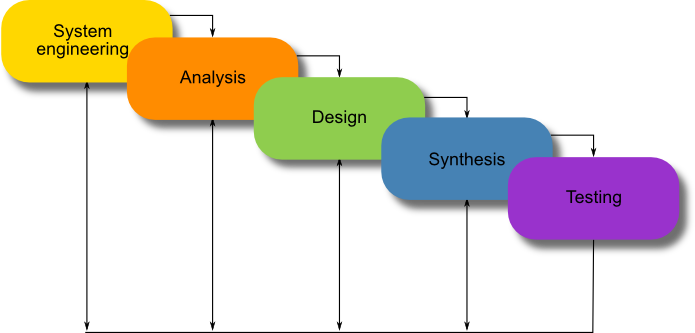

Unlike the waterfall model, there is currently no need for the maintenance phase in synthetic biology.

We propose the model in Figure 1 to fit Synthetic Biology. It is important to note the iterative nature of the software development life cycle which was also inherited by our proposed Synthetic Biology life cycle.

Figure 1: A proposed development life cycle for Synthetic Biology.

Using CellML

The modelling language of choice for virtual parts is CellML. One of the main reasons for choosing CellML over SBML (or any of the other modelling language available) is its modular nature and its proven track record in representing intracellular processes in systems biology (Cooling et al., 2010). Identifying motifs

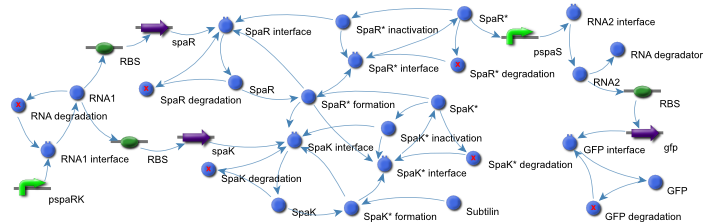

To identify motifs and the parts they were composed of, the CellML model of the subtilin receiver was converted to a graphical representation (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A graphic respresentation of the Subtilin Receiver model.

The virtual parts for these parts were extracted from the CellML Subtilin receiver model and assembled again in a new file.

The model in the file was checked using [http://cor.physiol.ox.ac.uk/ COR] because it was quick to reload changed files and to return informative errors Database

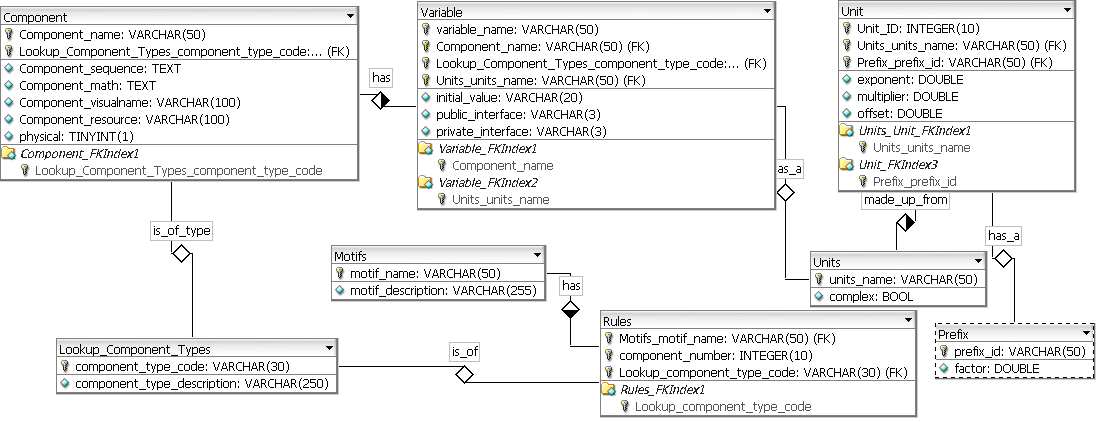

A MySQL relational database was designed and created to hold both physical and non-physical virtual parts, required to build a simulatable model of a BioBrick. Both types of parts are saved in the same table but are distinguished by a boolean flag.

The database was populated to hold at least one generic part for each type of part that we used. A naming convention was adopted allows for the retrieval of parts based on the part name.

The structure of the database is shown in the E-R diagram in Figure 3.

Figure 3: An E-R diagram of the database created for the BioBrickIt service, to hold virtual parts and motifs. (Click on image for larger format)

Web Service

A web service, which we called BioBrickIt, was developed in Java and served with the Apache Tomcat web server. The web service provides the functionality to populate the database with virtual parts and other information required to create simulatable CellML models. It further provides the functionality to simulate models retrieved.

A choice had to be made between offering a SOAP or a RESTful web service. Time constraints and simplicity of implementation favoured a RESTful service. Resources are exposed as URLs and results are returned as plain text rather than in XML, as would be the case if it was a SOAP service (Pautasso and Leymann, 2008).

The web service accesses the relational database discussed in section 2.4 using Java DataBase Connectivity (JDBC).

The web service can retrieve a simulatable model of a motif by firstly retrieving its rules.

Simulation

Simulation of models were provided by connecting the web service to an instance of JSim. JSim (http://www.physiome.org/jsim/) is a software application, written in Java, for simulating quantitative numeric models. It is possible to run JSim as a service, a stand alone application or an applet.

The JSim server was installed on the same server as the Apache Tomcat web server.

Simulation is requested from the BioBrickIt service by passing the parameter simulation=true with the URL when a model of a motif is requested.

Taverna workflows

To create the workflows that utilised the web service, the decision was made to use [http://www.taverna.org.uk/ Taverna Workbench]. Taverna is an open source application for managing workflows. It can be used to integrate molecular biology tools and databases available on the Web. It is especially useful for web services (Hull et al., 2006). Taverna was chosen because of familiarity with the product, but also because time restrictions did not allow for the evaluation and comparison of other tools.

Results:

Motifs

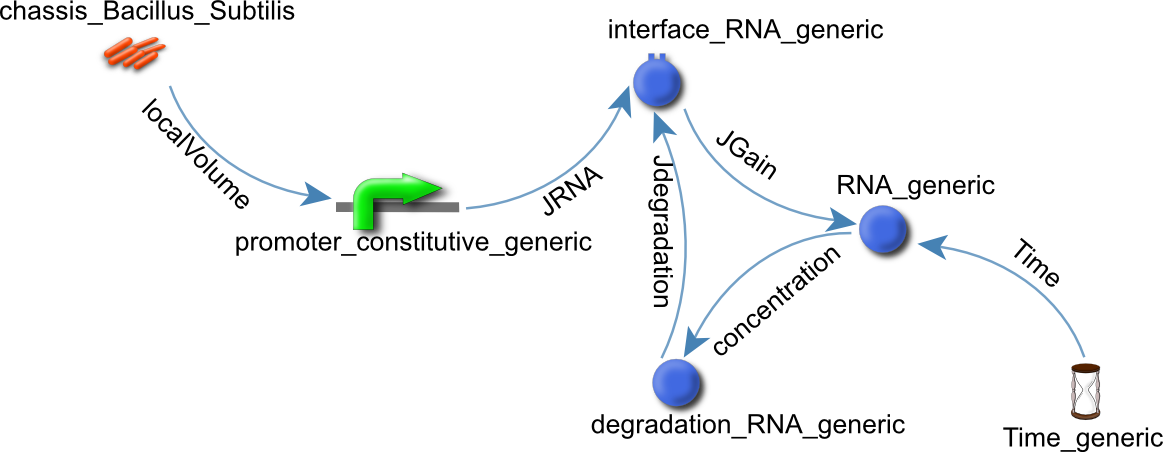

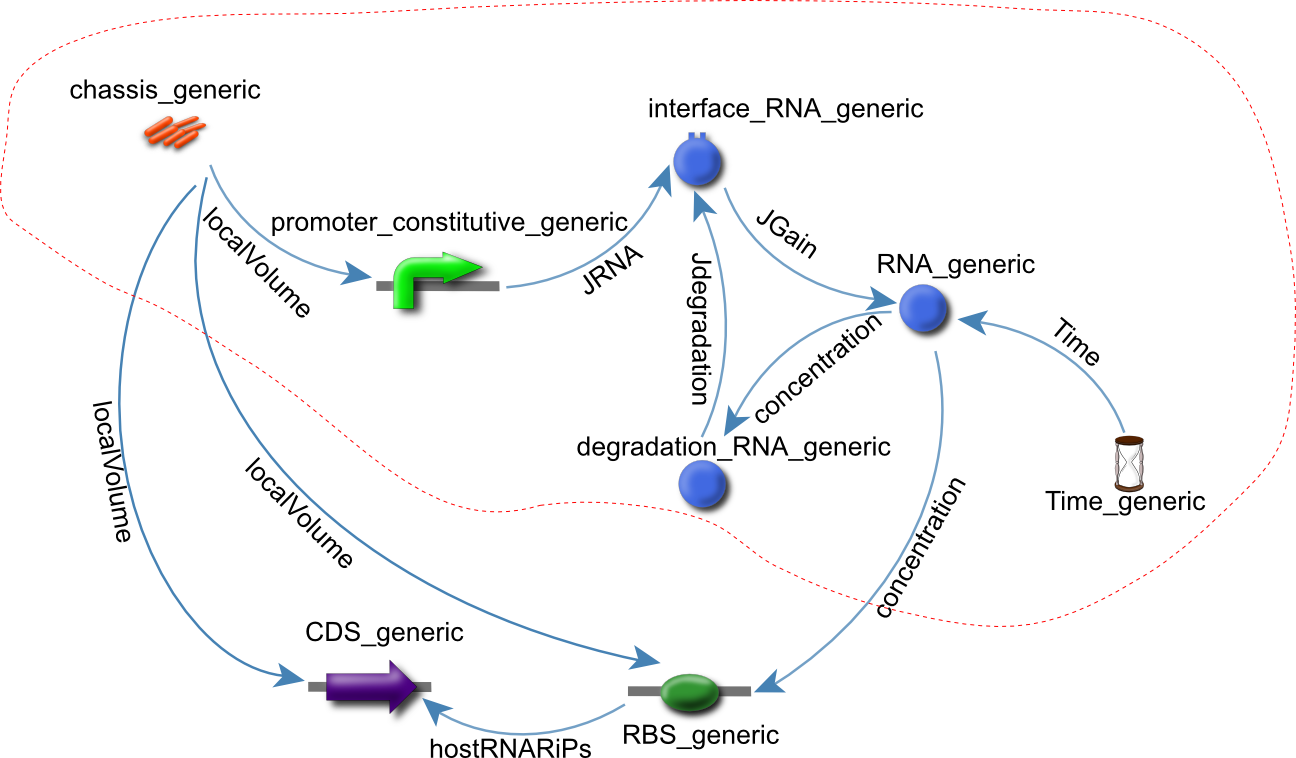

We identified two motifs, a constitutive promoter motif and a coding sequence motif (see Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1: The constitutive promoter motif.

Figure 2: The coding sequence motif.

The coding sequence motif illustrates how a modular approach can be beneficial to the design process. The constitutive promoter motif that is embedded in the coding sequence motif is shown with the red dotted line.

The motifs were identified using the Subtilin receiver model created by the Newcastle University iGEM team of 2008.

The BioBrickIt Web Service

We developed a RESTful web service which we called BioBrickIt. It is available online at http://msc.jannetta.com:8080/BioBrickIt. BioBrickIt was developed using J2EE web technologies, JAXP for XML handling, the Apache Tomcat web server and a mySQL database. The service and its source code can also be downloaded as a .war file from http://msc.jannetta.com:8080/BioBrickIt/BioBrickIt.war.

The web service exposes the following resources: Adding a component (or virtual part) to the database from a file containing the part in cellML format

- Listing all the components in the database

- Listing all the component types in the database

- Listing all the variables for a specified component

- Retrieving a specified component

- Listing the sequence for a physical component

- Listing all the motifs in the database

- Listing the rules for a specified motif

- Retrieving the model for a specified motif

- Simulating the retrieved model

Database

A MySQL relational database was designed and implemented to hold both physical and non-physical parts. The database was populated manually and using the file upload feature of the BioBrickIt web service. A set of generic parts was all that was required for this research, but the database contains several other parts which are available from the 2008 iGEM Subtilin receiver. The database is online and can be accessed via the BioBrickIt Service at http://msc.jannetta.com:8080/BioBrickIt/.

JSim server

When accessing the BioBrickIt service on http://msc.jannetta.com:8080/BioBrickIt/, a simulation of the generated motif can be requested. This is done by adding simulate=yes as a parameter to the URL. For example requesting a simulation of the generic constitutive promotor can be obtained with: http://msc.jannetta.com:8080/BioBrickIt/GetMotifModel?motif_name=motif_constitutive_promoter&simulate=yes.

Taverna workflows

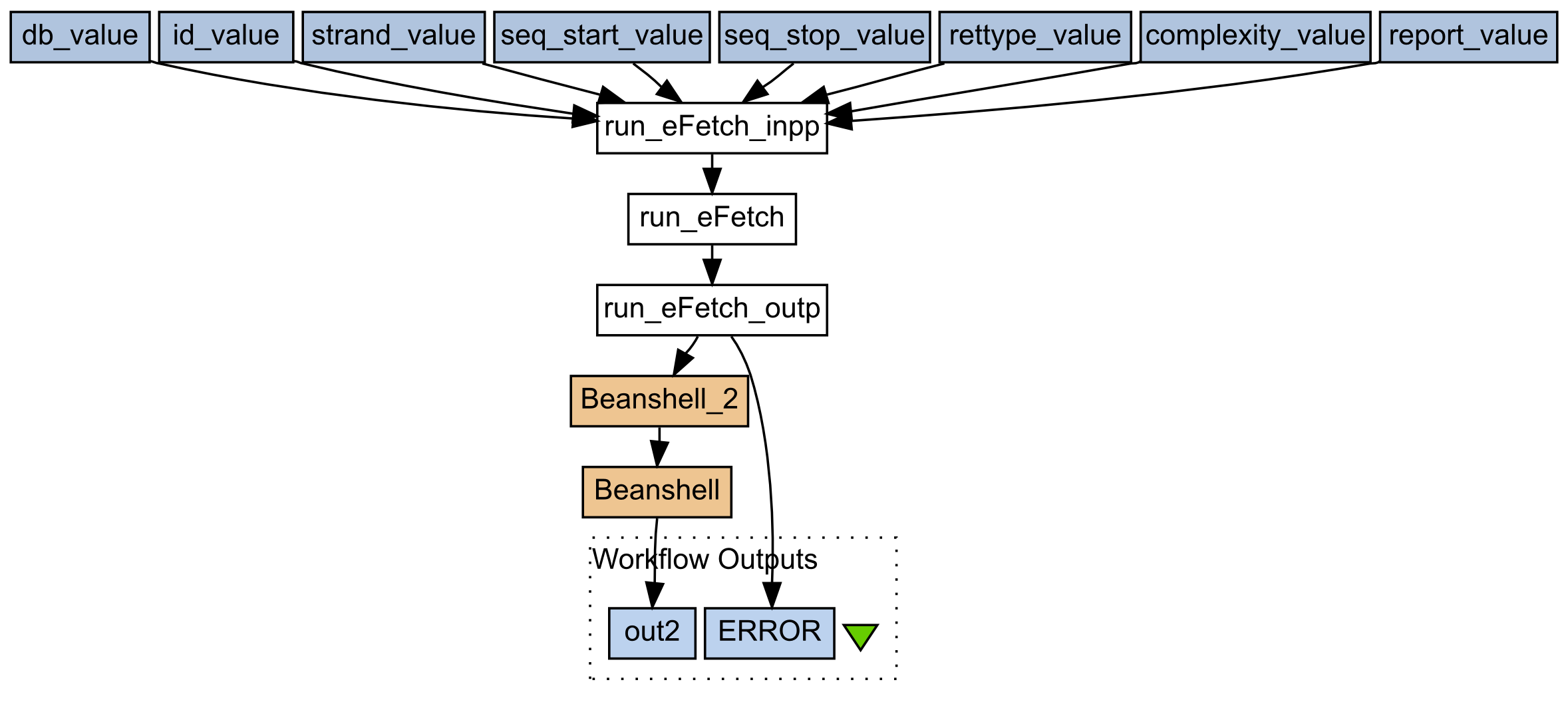

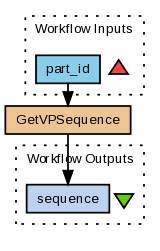

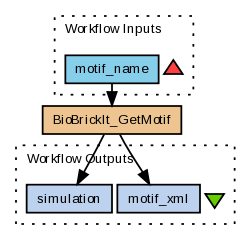

We used Taverna Workbench to create 3 workflows. The first workflow (Figure 3) makes use of the BioBrickIt Webservice to determine the presence of restriction sites in a provided sequence.

The second workflow (Figure 4) retrieves the sequences of provided physical parts using the BioBrickIt service. It then concatenates the sequences. The intension is that this workflow be extended or embedded in a larger workflow that could conver a CellML model to a sequence.

Figure 3: Workflow 1, Restriction site finder.

Figure 4: Workflow 2, Retrieve sequences of virtual parts.

Figure 5: Workflow 3, Retrieve simulatable CellML model of a motif.

Discussion:

Synthetic Biology is a very young field of study and still lacks the methodologies already established in other fields of engineering. To speed up the process of putting these methodologies in place, it makes sense to borrow from the other engineering disciplines. Systems biology already makes use of an e-Science approach using computerised workflows with great success. The approach serves to avoid tedious cutting and pasting of retrieved result from one software package to the next and thus saves significant amounts of time and effort to improve efficiency and accuracy.

Using the bottom-up approach to design, means that design starts with the most simple of identifiable parts, working its way up to a complex system composed of these parts (Cooling et al., 2010). This approach relates very closely to the development of software and fits in very well with a design and development approach similar to the software development life cycle. Thus, we proposed a Synthetic Biology life cycle which, apart from one phase, is almost identical to the SDLC.

The subtilin receiver model created by Cooling et al. (2010) provided all the virtual parts necessary for this research project. Creating a graphical representation of the model allowed us to identify the motifs which provided the first level of abstraction and encapsulation. The principles of abstraction and encapsulation were borrowed from software and serve the purpose of hiding the complexity of a design (Henderson-Sellers, 1997). Models consist not only of physical parts, but also need non-physical parts that glue the physical parts together for simulation purposes. These physical and non-physical parts provide the minimal parts required in the bottom-up approach. The rules for putting these parts together were captured in a database which allowed us to query the database for a series of parts in the correct order almost ready for simulation. Once the parts are extracted from the database according to the rules, programmatically extract the units that need to be specified in the model and the connections that need to be made between parts. A naming convention which allowed us to determine which variables from which parts need connecting. An alternative approach would be to extend the database to hold the information required for mapping parts and variables. This approach would simplify the creation of the CellML parts, but would complicate the design of the software and database.

With the database in place and populated we developed a RESTful web service that extracts the parts required for a requested motif, assemble the motif and returns it in CellML as a simulatable model. The service can return the CellML to the client, but it can also simulate the model using JSim, a Java based software application. Three services, a database service, a web service and a simulating service were established. Finally a Taverna workflow was created that use these services in order to create a generic simulatable model. The parts of the generic model can, for the moment, be replaced manually with specific parts. Ideally the service should be extended to replace parts automatically so that minimal input is required from the user.

Although all of the above mentioned services were installed on one server it is possible to develop these services such that they can be run on different servers and off course in different locations on the Internet.

A variation on the waterfall software development life cycle was suggested and it was illustrated how this method can successfully be used to guide the design process. It is, however, a very old method and software engineering has produced many alternatives since. It would be worth while investigating some of the newer methods that might prove to be even more successful if applied to the Synthetic Biology development life cycle.

Putting it all together

Figure 1 shows, from start to finish, the internal flow of information in an ideal workflow that would produce a complete and simulated model of the requested part or motif. The workflow includes the workflows already created as well as the services provided by BioBrickIt. To actually be able to implement the complete workflow both BioBrickIt and the Taverna workflows created will need extending.

The process is started with input by the user (Figure 1(a)), specifying which motif and which specific parts are required.

The next step. (Figure 1(b)), is to retrieve the motif with generic parts from the database. The motif is composed of virtual part and assembled according to the rules which are also capture in the database. This motif is simulatable as is, but contains no specific parts as yet.

Step 3, (Figure 1(c)), uses a service, such as BioBrickIt, that can use the generated motif and replace generic virtual parts with specified parts of the same type. For instance, a generic constitutive promoter can be replaced by pspaRK.

Step 4, (Figure 1(d)), uses a service such as JSim to simulate the model. To make sense of the simulation results it is usually required to visualise it in some form. Visualisation is done in step 5.

Step 5, (Figure 1(e)), produces human readable formats of the simulation results. Visualisation is usually in the format of graphs.

Step 6, (Figure 1(f)), is the production of a BioBrick sequence from the produced model produced in step 3. Newcastle University is currently researching such a model-to-sequence conversion algorithm. This step would make use of the GetVPSequence and GetSites workflows, to retrieve physical part sequences and check them for specified restriction sites.

Step 7, (Figure 1(g)), show the possible results that can be produced by the workflow.

Figure 1 (This image is 1.1 MB and might take a while to download.)

|

"

"