Team:Queens-Canada/digestive

From 2010.igem.org

The Digestive System

The C. elegans digestive system is divided into two components: the pharynx, which breaks down food by grinding it up, and the intestine, where food is digested, absorbed, and stored. The intestine is a major component of the worm, by mass a whole third of its somatic cells, and presents many interesting opportunities for synthetic biology through the prospects of enterosymbiosis with bacteria and the potential localization of catalytic pathways.

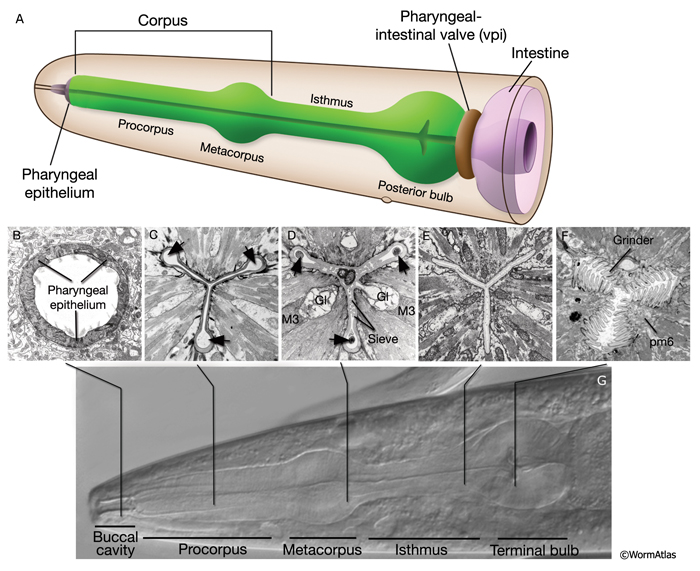

The Pharynx

From WormAtlas

The pharynx is a complex structure that precedes the intestine. Quite unlike the human pharynx, it is a combination of pump and grinder, and it has been theorized to bear some homology to the heart of other organisms based on its selection of ion pumps, developmental independence, and the nature of its innervation.

The pharynx normally takes in bacteria-filled water, pushes the water back out, grinds up the bacteria, and then passes them along to the intestine. The grinder, located in the terminal bulb, is very fine, and unless disrupted by the activity of a pathogenic bacterium, cuts up the food. The pump rate is dependent on the detection of food and recent periods of starvation, but it never stops.

One of the primary interests synthetic biology may have with the C. elegans pharynx is in circumventing its behavior sufficiently for symbiotic, beneficial colonization of the worm’s intestine by an engineered bacterial strain (enterosymbiosis). While this goal may seem remote at first inspection, consider that [http://www.wormbook.org/chapters/www_intermicrobpath/intermicrobpath.html#d0e691 there are a number of bacteria] which already interfere with the nematode’s grinder and colonize the intestine as pathogens, and that this manner of symbiosis already exists stably in other nematode/bacteria systems, as documented in [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2005.11.016 Ciche et al. 2006], for the ultimate purpose of infecting insects with the bacteria. Ciche et al. also document a number of genes required for these systems to function properly; it might be possible to transfer some of them into C. elegans and E. coli to develop a reliable cooperativity.

The pharynx of C. elegans is far removed from most other cell lineages developmentally, and so is easy to target in terms of promoters, although our initial chassis offering focuses more on the general nervous system. The pharynx’s nearly-isolated nervous system controls pump rate, innervates the muscle cells to pump, and is consulted (along with many other sources) in establishing the dauer decision, but most other communication with the rest of the organism is probably done through hormones (see our section on the pseudocoelom). Other than as a component of enterosymbiosis projects, the potential usefulness of the pharynx in synthetic biology does not appear great to us, but there are surely many possibilities we have not considered.

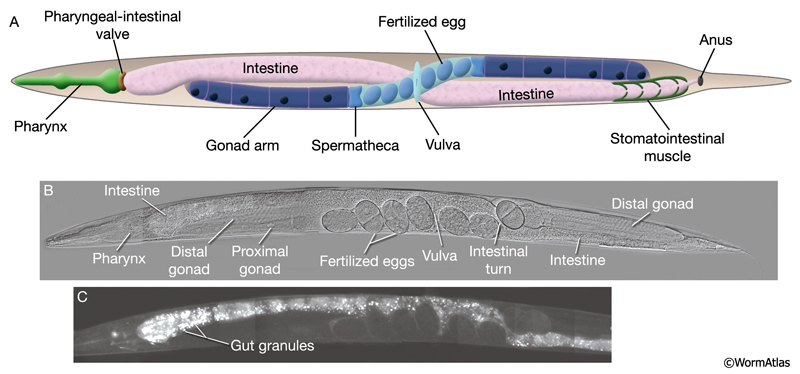

The Intestine

From WormAtlas

The intestine is a long tube that spans most of the creature’s body. It is comprised of twenty cells which form rings down the length of the worm’s interior. With the exception of the grinding activity provided by the pharynx, and defecation provided by the anus, the intestine of C. elegans performs most of the digestive functions of higher organisms, including chemical breakdown of food, absorption of nutrient molecules, and synthesis and storage of fats. For a long time, the worm’s digestive system was very poorly understood, but this is steadily being corrected in combination with knowledge of the digestive systems of other nematodes.

The pH of the intestine is not known precisely, but studies of various catabolic enymes known to be localized to the intestinal lumen suggests that it is probably somewhere between 4 and 5. (This is much more mild than the human stomach.) As one of the greatest promises of the intestine is to create a synthetic pathway of some sort within the organ, and to use the natural excretion process to separate the product from the worm, this could potentially complicate pathways that require proteins which function optimally at higher pHs, as most do. One way around this might be to compose the product inside of the intestinal cells and then export it. The promoter and 5' UTR of pho-1 [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15733671|are known] to be specific only to the later end of the intestine, which could reduce the exposure time to acid, or allow for a multi-stage synthesis process that progresses down the intestine. If pH and the presence of digestive enzymes could potentially pose a threat to the safe production of some product, however, it may make more sense to move such a project into the excretory system instead.

Several of the cells in the worm’s intestine have two nuclei after the L1 stage of larval development. The purpose and value of this is not known, and preventing it by knocking out the gene lin-14 does not seem to affect the worm adversely. This property may be potentially exploitable as a means to insert a foreign molecule into the nucleus before telophase begins after this superfluous division. The intestine is something of a hot spot for peculiar nucleic acid activity—dsRNA is normally taken up in the intestine, through the SID-2 channel lining the lumen, and then propagates throughout the worm (except neurons) via SID-1.

Although nematodes in general typically grind up bacteria before they reach the intestine, there are some cases in which bacteria circumvent the normal pharynx function and successfully colonize the intestinal surface, with typically detrimental effects to the host worm. Several species are known to attack C. elegans in this way, and worms particularly vulnerable to intestinal colonization due to mutations are said to be of the BUS phenotype; a family of genes has been named bus, appropriately. However, there are other nematode species where colonization isn’t doom for the worm: Steinernema carpocapsae, a parasitic nematode that parasitizes wasp larvae, [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17618298 forms an effective symbiosis with the bacterial species Xenorhabdus nematophila], which is necessary for killing the insects and assisting the worm’s mode of reproduction.

No immediate barrier is apparent to the thought of transferring the genes that make this colonization possible into C. elegans and E. coli, although this is obviously a great deal of work, and the tendency to retain bacteria as engendered in bus mutants can most likely reproduce the effect at a sufficient rate and worm longevity for most projects. Like the exosymbiosis suggested in the cuticle article, this system of enterosymbiosis presents a great opportunity for inter-kingdom cooperation and backward compatibility with the fundamental E. coli chassis.

Continue to the Nervous System

"

"