Team:EPF Lausanne/Project droso

From 2010.igem.org

Contents |

Introduction

The final goal of our project is for our modified Asaia to survive and produce proteins in the mosquito's gut. However, working with mosquitoes, requires special equipment that we do not have at EPFL. We wondered if we could work on another insect which is less demanding, and therefore turned towards Drosophila (commonly known as the fruit fly), which is much easier to work with.

Considering the fact that bacteria that live in the guts of insects are not very common, we assumed that there was a fair chance that Asaia could persist in Drosophila and that we could use the it as an alternative to mosquitoes for our basic experiments.

We therefore decided to work in a first phase with Drosophila, which we discuss in the first part of this section, and finally turn to mosquitoes, which we discuss in the second part of this section.

I) Experiments on Drosophila

Using Drosophila melanogaster we aimed to address two questions:

i. Is Asaia toxic for Drosophila?

ii.Is Asaia able to colonize the Drosophila gut and persist?

(See Materials and Methods for details on how the experiments were conducted.)

Our main results

1) Asaia is not toxic for Drosophila

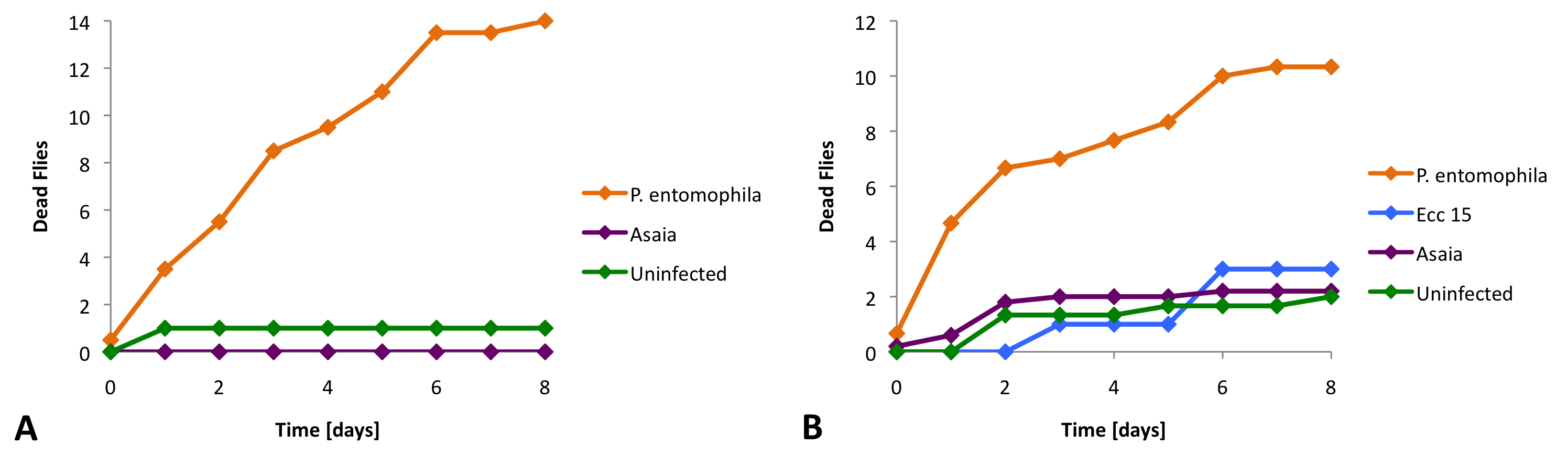

We infected Drosophila with different bacterial strains, a pathogenic control starin (P. entomophila), a non-pathogenic control strain (Ecc 15) and our Asaia bacteria. For these experiments we used two different fly strains (Oregon and Relish).

We found that Asaia does not cause significantly more deaths than the non-pathogenic bacteria or in the uninfected control (Figure 2).

2) Asaia is not persistant in Drosophila

With this last experiment we wanted to ascertain wether asaia persisted in drosophila and quantize how many asaia were present in the drosophila’s gut after 3h, 24h and 48h.

To be able to “count” the number of asaia at these three different periods of time, we had to retrieve the bacteria inside the flies, plate them and after incubation count the number of colonies present.

To do this we disinfected the exterior of the flies by washing them with ethanol (for less than five seconds) and then rinsing them with water. The flies were then crushed in the medium corresponding to the bacteria we were interested in (i.e: Gly for asaia, LB for Pe, etc). We then did a serial dilution eleven times with a factor of ten with the crushed flies, and plated each dilution with antibiotics to specifically select the bacteria we were interested in.

Conclusion to the drosophila experiments

The survival assay reveals that Asaia is not lethal for Drosophila.

The persistence assay showed that Asaia is unable to establish itself in the fruit fly's gut. This prevents us to use Drosophila as a substitute to mosquitoes.

As mentioned before, bacteria that live in insects’ gut are not common and it is possible that because it cannot survive in Drosophila, it is actually very specific to mosquitoes. With this assumption, we could assume that we can introduce our modified asaia into the wildlife with very little risk of it spreading to other insects.

II) Experiments on mosquitoes

The final objective of this project is to determine if mosquitoes carrying our engineered Asaia are less capable of transmitting malaria. To do so we contacted the Institute Pasteur in Paris to collaborate with us and proceed with our experiments. Nevertheless, we did not manage to arrive to this stage before the iGEM jamboree, so we cannot show our results. We are still discussing with them on the experiments and on how we are going to proceed.

"

"