Team:Groningen/Biofilm

From 2010.igem.org

Biofilm

Summary

In our project we want our host bacterium to not only produce the coating material, but also apply it. Therefore we chose Bacillus subtilis as our host bacterium. B. subtilis can form a rigid biofilm that will cover the target surface before producing the hydrophobic proteins. As part of our project we made a model on the biofilmformation, but furthermore we looked into ways to easily apply B. subtilis to the surface and let it form a biofilm there. One way to do this is by adding corn starch to regular TY-medium, making it an easily applicable paste.

Introduction

Using biobased materials in the application or manufacturing of coatings has been the topic of many researches. However, using bacteria to make a coating substance and, most importantly, letting it do the coating process for you is something new. In our hydrophobofilm project we aim to use the extracellular fibrous proteins, DNA and polysaccharides that are formed in a biofilm, as a host matrix to embed our coating material, which in our case are hydrophobic proteins.

Growing a biofilm on a surface as a way of coating it, might seem like a bad idea, since there are quite a lot of coatings out there to prevent biofilms forming in the first place. But why not "fight fire with fire”, and create a biofilm that is non-pathogenic and prevents other biofouling from taking place.

Bacillus subtilis is an ideal candidate for a biofilm coating. Firstly because it is quickly grows a biofilm which has a smooth extracellular matrix. Secondly, the bacterium is a well known and extensively studied model organism which makes is easier to work with. Finally B. subtilis is a gram-positive bacterium like Streptomyces coelicolor, the bacterium that naturally produces hydrophobins. This might be an advantage when expressing and assembling the chaplin proteins in our host.

Biology

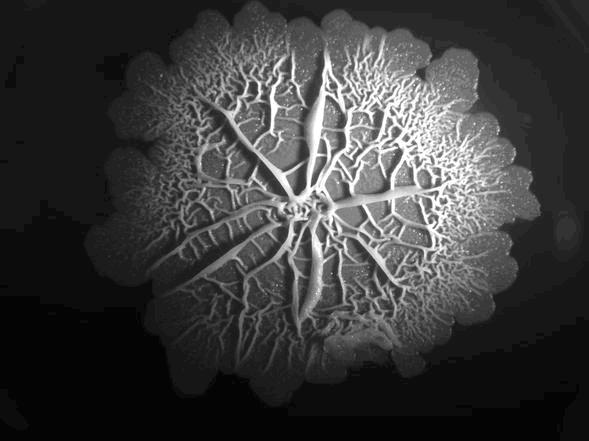

In nature, bacteria occur predominantly in highly organized multicellular communities called biofilms. Biofilm formation involves a complex developmental process, where cells differ from each other spatially and morphologically. The bacterial cells in biofilms are phenotypically different, demonstrating an intriguing example of heterogeneous regulation within an isogenic culture. Gram-positive bacteria have developed different strategies for survival in unfavorable environments, e.g. by getting competent or by sporulating. Biofilms offer an opportunity for the cells to survive extreme conditions as the cells in biofilms are more resistant to antibiotics and other harsh circumstances like physical stress, drought or competing organisms. Bacillus even forms highly complex biofilms with a large degree of structural complexity and diversification of cell function within the biofilm. There are even channels within the biofilm to allow drainage of waste and diffusion of oxygen deep within the biofilm.(Akos Kovacs)

Biofilm formation usually starts with the accumulation of biomass, next there is the adhesion to a surface by the production of adhesion proteins. Then the production of "extracellular polymeric substances" (EPS) starts and the phenotypic diversification. After maturation of the biofilm sporulation kicks in. Since the pathways involved in biofilm formation in B. subtilis are just starting to be unravelled, not everything is known about the complex physiological interactions within a biofilm. By using an already existing pathway in B. subtilis for the auto-induction of our hydrophobic proteins, we try to minimize the amount of tinkering to the existing signaling pathways. Thereby leaving the natural system intact.

Timing is one the most important factors in successful assembly of our chaplins in EPS. B. subtilis produces a protein that forms amyloidfibers called TasA. TasA is a very important protein to provide structural integrity in B. subtilis biofilms and is formed in the late stage of biofilm formation. The amyloid fibers that are formed provide the biofilm with an increased degree of rigidity (Romero et al, 2009). Chaplins also assemble into amyloid fibers and provide a similar function in the hyphae of S. coelicolor (Cleassen et al, 2009), giving the hyphae the structural ability to grow high up in the air. Incorperating the chaplins at the same moment as TasA is formed would maximize the chance of successful assembly of chaplins in the EPS, while enabling maximum biofilm coverage. For more details on our expression pathway check out our expression or modeling page.

Coating surfaces

Prevention from our biofilm to grow out of control, is an important aspect when you would apply the hydrophobofilm outside the lab. To deal with these safety issues we modelled a kill switch for our hydrophobofilm. This kill switch relies on the production of a toxin and anti toxin. Where the anti toxin has a slightly shorter half-life than the toxin, thereby eventually resulting in the toxification of the cell itself. This toxification would occur after maturation of the biofilm. After the autotoxification the cells, the EPS with the embedded chaplin proteins will dry out, leaving a hydrophobic EPS layer on the surface.

Applying our bacteria effectively to a surface poses big challenges. such as, how to coat a surface in a short period of time, with low cost and low tech methods. Furthermore there must be enough nutrients for the organisms to successfully form a biofilm, yet you do not want to smear you surface in to much medium, so to avoid that the organism will only adhere to the medium and not to the surface itself.

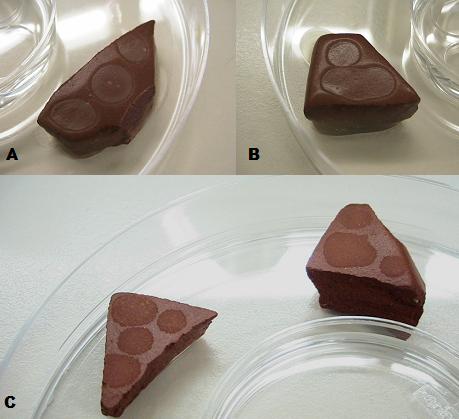

Biofilm paste We attempted to make a medium that could be easily applied to a surface and enable biofilm formation to take place. To achieve this we tried to make our medium more viscous. By adding corn starch to regular TY medium we increased the viscosity of our medium and also made it richer in nutrients. We experimented with different corn starch concentrations.

We have created an easily applicable paste, to grow our biofilmcoating on all kinds of different surfaces. Another effect of the addition of cornstarch to the medium is an increased growing speed.

A & B: B. subtilis biofilms grown overnight on ceramics coated with the biofilm paste. C: B subtilis biofilms dried out over four days, after formation.

References

1. Romero et al, 2009, Amyloid Fibers Provide Structural Integrity to Bacillus subtilis Biolms

2. Dennis Claessen, Rick Rink, Wouter de Jong, et al, 2009, A novel class of secreted hydrophobic proteins is involved in aerial hyphae formation in Streptomyces coelicolor by forming amyloid-like fibrils

"

"