Team:Johns Hopkins/Modeling

From 2010.igem.org

Contents |

Abstract

The expressed purpose of this model is to take the data obtained through experiment and simulate the actions of saccharomyces cerevisiae at different voltages. The yeasts, in SC complete media, were electroporated at various voltage to induce calcium ion intake through L-type voltage-gated calcium channels.[1] As yeasts have no sarcoplasmic reticulum, calcium will be imported largely from outside the cell. by following precedents set by the Reuter-Stevens (RS) and the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (GHK) models, the total charge in calcium imported into the cell during the period of electric stimulation was derived from the current-voltage relationship. The concentration of calcium taken into the cell was derived from the total charge imported, and used to determine the output of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). the model consists of two major parts: the calculation of calcium intake and the determination of transcription/translation levels induced by calcium. These results fit the data presented in the notebook.

Like the Valencia team in 2009, we utilized the stochastic approach through the analysis of gating through probabilistic variables. In fact, the stochastic model they utilized is not entirely accurate; recent literature suggests that the f2 inactivation gate does not play a role in yeast voltage-gated inactivation as much as in mammalian systems. By far, the largest improvement upon the mathematical modeling done by Valencia exists as that of the gene-to-protein modeling. Using the control system depicted in this model, we are able to predict the expression, and therefore, the luminescence of the yeast. The next step in advancing this prediction would be to fine-tune the control mechanism, preferably with Simulink.

The Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel

Assumptions

- [Ca2+]out is in excess compared to [Ca2+]in.[12]

- The experiment takes place at room temperature (25oC).

- the L-type Ca2+ (Cch1) channel is homologous to those found in other eukaryotes.[3]

- Any Ca2+ that enters into the channel will exit into the cell.

- The channel is specific and selective for Ca2+.

- The cell is at steady state previous to stimulation.

- There are two activation gates ('a') and two inactivation gates ('i').

- Gates of the same type are identical and independent in action.

- There are approximately 100 calcium channels per yeast cell.[1]

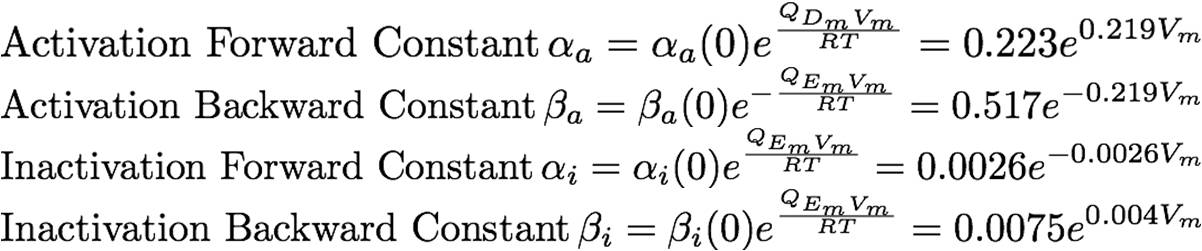

Constant Instantiation

the overall model of the calcium channel can be subdivided into its constituent gates: the activation gate and the inactivation gate. Collapsed into chemical formulas, the channel's interactions with the calcium can be thought of as such:

Based off the assumption that any bound calcium must travel inside, the result:

These may be further subdivided into the activation and the inactivation gates:

The rate constants are provided below:

The Calculation of Voltage Experienced at the Cellular Level

Although the electrodes registered voltages in volts, the individual changes felt by the individual cells in the SC media are estimated to be in millivolts. In particular, a recursive algorithm was used to calculate the optimal voltage wherein charge (from calcium) transport across the membrane occurred at the greatest rate. The MATLAB function fsolve was utilized to find this point. It reflects the observed data as seen in the notebook: the optimal point was found to exist at roughly 0.007-0.008 V, or 7-8 mV.

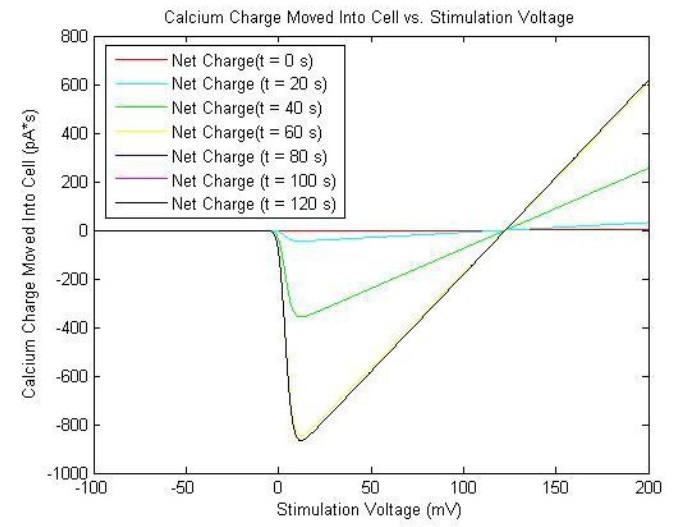

Calculation of Charge Intake

The charge intake is usually dependent on two variables: stimulation time and stimulation voltage (received).[6] The dependence can be reduced to one variable by varying the stimulation voltage at fixed stimulation times. Simultaneously, it is useful to construct, as per the RS model, a relationship between the calcium current and membrane voltage, at various stimulation times. From Ohm’s Law, it is known that V = IR. Therefore, the equation may also be written as:

In this case, the current would consist solely of calcium ions moving into the cell.[12] Also, it is required that the term GV be scaled by the probability of the channel being open, and also by the number of channels per cell. Thus, current may be written as:[2],[13],[14]

or,

The Nernst Potential of calcium can be considered to be roughly 123 mV, under physiological conditions.

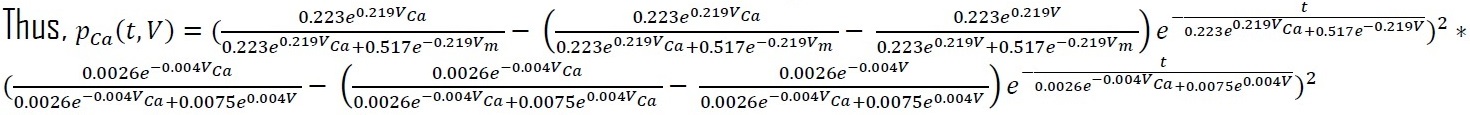

![]() exists as the probability that both inactivation gates and both activation gates are open. Therefore,

exists as the probability that both inactivation gates and both activation gates are open. Therefore, ![]() may be modeled as such:

may be modeled as such:

Bear in mind that this, as is the RS model, is a stochastic model. By calculating the steady state values of ![]() and

and ![]() from the differential equations:

from the differential equations:

And

The solution of the differential equations above takes the form:

Therefore, the current may be written as:

The solutions are plotted as such:

The reason that the current is negative is that by convention, the inward diffusion of calcium ions is called inward current, since it diffuses into the cell.[5] Therefore, one must remember to take the negative of the current to obtain its magnitude. The relatively small magnitudes of and render the channel relatively insensitive to inactivation, and as such, the action is mitigated by negative feedback from the calcium binding to calmodulin and calcineurin. This will be discussed further in the Calcium-Induced YFP Transcription/Translation.

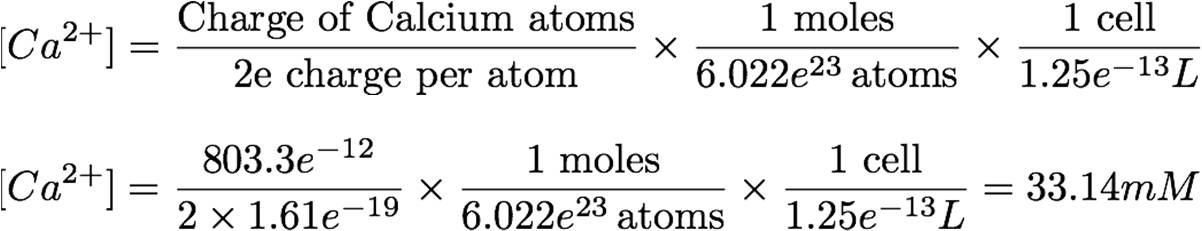

Derivation of Calcium Intake and Post-Stimulation Calcium Concentration

The amount of calcium taken into the cell, and therefore the post-stimulation concentration, can be derived from the current taken at the ideal stimulation voltage (8 mV), during the ideal shock time (60 s). The idea behind the equation is simple: the total instantaneous charge will be taken, divided by 2x elementary charge, then divided by Avogadro’s number to obtain the number of moles taken in. This is then divided by the volume of the cell (1.25e-13 L) to obtain the post-stimulation concentration.[1],[10]

This concentration of calcium will be the input from which YFP transcription is derived.

Calcium-Induced YFP Transcription/Translation=

Assumptions

- Entry into the nucleus occurs by diffusion, on the scale of several minutes.

- YFP takes more than a day to significantly degrade.

- Calcium first binds to Calmodulin; it is assumed that all of this bound calcium will bind to Calcineurin.

- The cells used are diploid yeast cells.

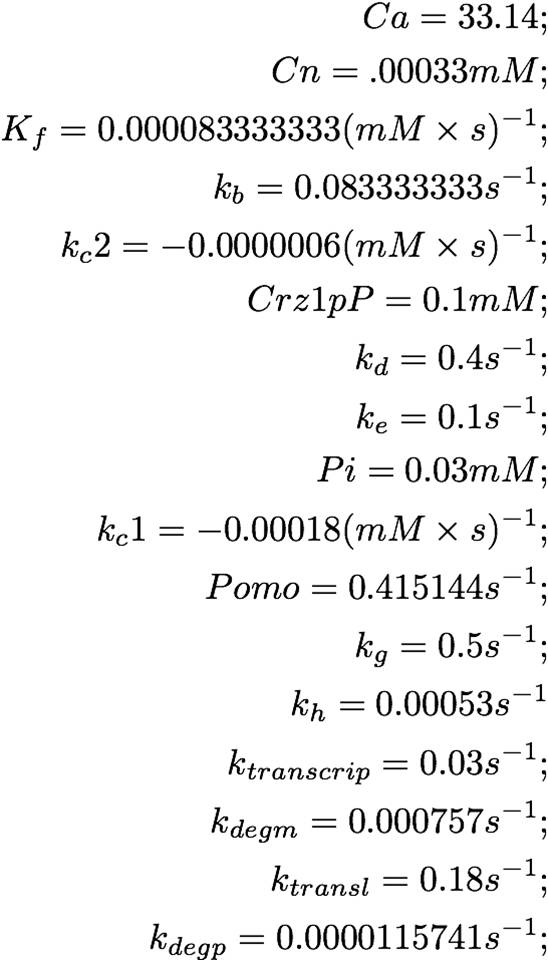

===Constant Instantiation===[4],[7],[8],[11],[12]

Setup of the System and Solution (YFP concentration)

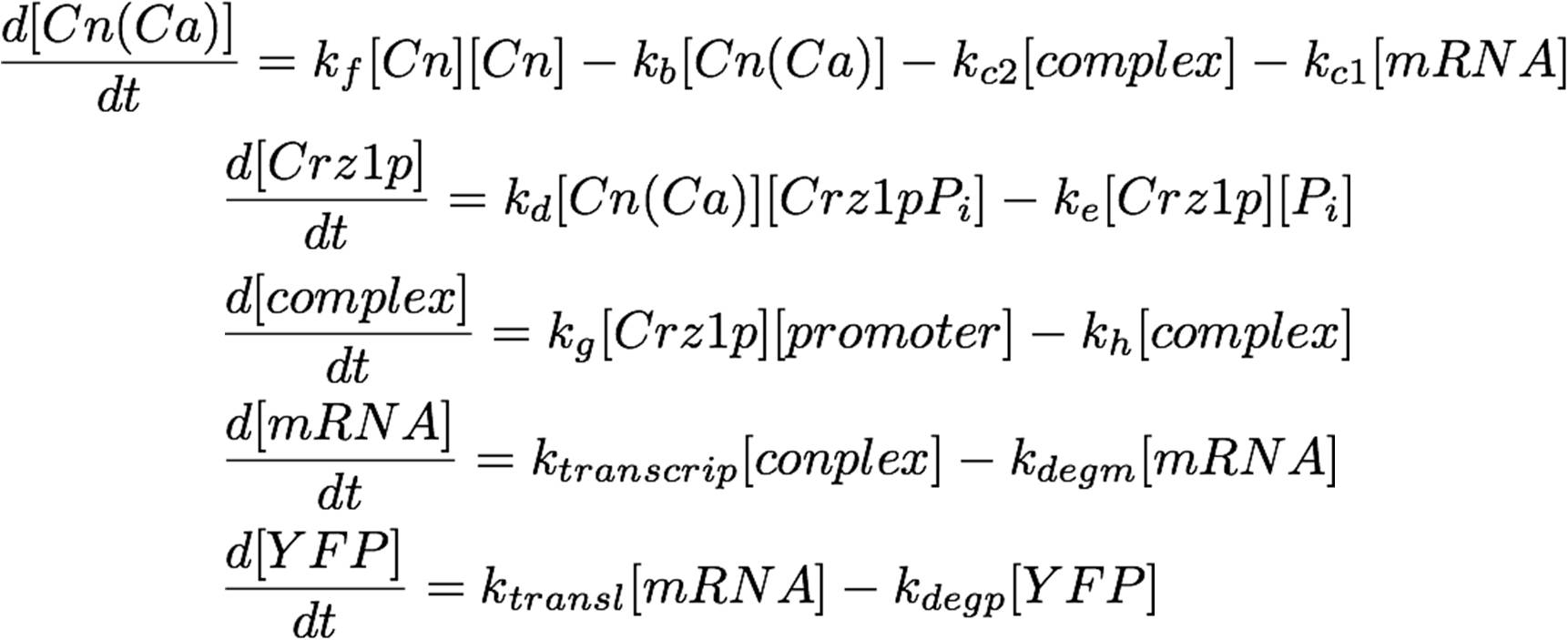

The system as pictured in the abstract can be represented as a system of differential equations:

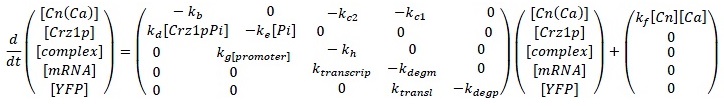

This equation can easily be placed in vector-matrix form, which can be solved numerically by MATLAB. Observe:

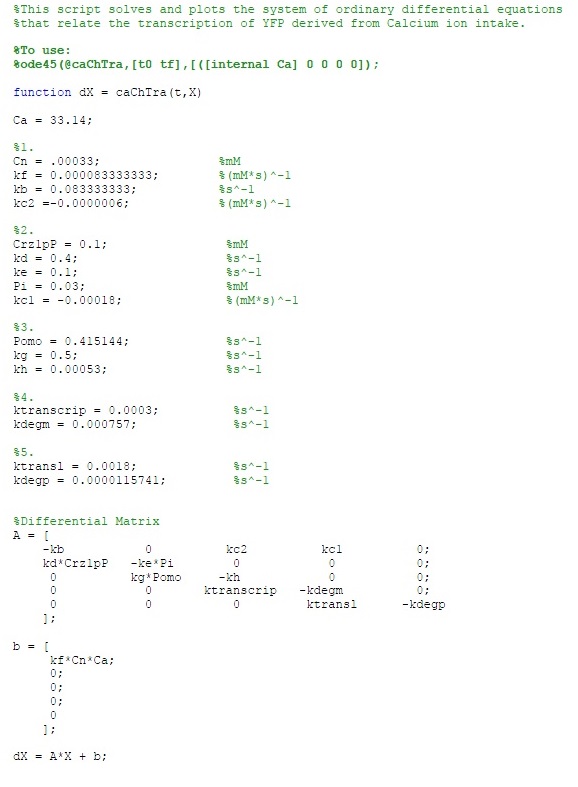

The MATLAB code is as follows:

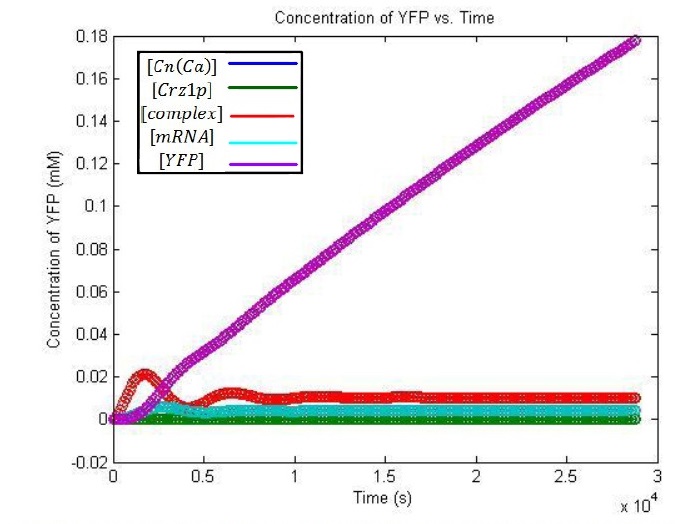

The solution of the problem:

From this graph, it is evident that the YFP concentration will grow to detectable levels by the time it is imaged, 3-8 hours later. The linearly increasing portion of the YFP concentration curve will taper off and decrease after a day or so, once degradation begins to take effect.

References

1. Cch1 Restores Intracellular Ca2+ in Fungal Cells during Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress

J.Biol. Chem. 2010 285: 10951-10958.First Published on February 1, 2010

2. Comparison of Greenhouse Grown, Containerized Grapevine Stomatal Conductance Measurements Using Two Differing Porometers

Thayne Montague*, Edward Hellman, and Michael Krawitzky

Texas AgriLife Research and Extension Center, Lubbock, Texas, U.S.A. 79403-6603

Department of Plant and Soil Science, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, U.S.A.

3. Comparative Analysis of the Kinetic Characteristics of L-Type Calcium Channels in Cardiac Cells of Hibernators

Alexey E. Alekseev,*t Nick 1. Markevich,* Antonina F. Korystova,* Andre Terzic,* and Yuri M. Kokoz*

Institute of Theoretical and Experimental Biophysics,* Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushchino, Moscow Region, Russia; and *Division of Cardiovascular Diseases, Departments of Internal Medicine and Pharmacology, Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota, USA Biophysical Journal Volume 70 February 1996 786-797

4. Determination of in-vivo cytoplasmic orthophosphate concentration in yeast

Uwe Theobald, Jochen Mohns and Manfred Rizzi From the issue entitled "Published in conjunction with Biotechnology Letters" BIOTECHNOLOGY TECHNIQUES Volume 10, Number 5, 297-302

5. Functional Expression of a Vertebrate Inwardly Rectifying K+ Channel in Yeast

Weimin Tang, Abdul Ruknudin, Wen-Pin Yang, Shyh-Yu Shaw,Aron Knickerbocker, and Stephen Kurtz'Molecular Biology of the Cell Vol. 6, 1231-1240, September 1995

6. Increased large conductance calcium-activated potassium (BK) channel expression accompanied by STREX variant downregulation in the developing mouse CNS

Stephen H-F MacDonald1,4 , Peter Ruth2 , Hans-Guenther Knaus3 and Michael J Shipston1 1 Centre for Integrative Physiology, School of Biomedical Science, Hugh Robson Building, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, EH8 9XD, UK BMC Developmental Technology, 2006.

7. Mathematical modeling of calcium homeostasis in yeast cells

Jiangjun Cui, Jaap A. Kaandorp Section Computational Science, Faculty of Science, University of Amsterdam, Kruislaan 403, 1098 SJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands

8. Measurement of the binding of transcription factor Sp1 to a single GC box recognition sequence.

J Letovsky and W S Dynan Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Colorado, Boulder 80309. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989 April 11; 17(7): 2639–2653.

9. Metabolic consequences of a species difference in Gibbs free energy of Na+/Ca2+ exchange: rat versus guinea pig

P. J. Cooper, M.-L. Ward, P. J. Hanley, G. R. Denyer, and D. S. LoiselleDepartment of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand

Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280 Vol. 280, Issue 4, R1221-R1229, April 2001

10.Permeation as a Diffusion Process

August 27, 2000 Bob Eisenberg Dept. of Molecular Biophysics and Physiology Chapter 4 in Biophysics Textbook On Line "Channels, Receptors, and Transporters" Louis J. DeFelice, Volume Editor http://biosci.umn.edu/biophys/OLTB/Channel.html

11. Promoter escape limits the rate of RNA polymerase II transcription and is enhanced by TFIIE, TFIIH, and ATP on negatively supercoiled DNA

Jennifer F. Kugel and James A. Goodrich*

Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Colorado at Boulder, Campus Box 215, Boulder, CO 80309-0215

Communicated by Olke C. Uhlenbeck, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, June 3, 1998

12. Protein phosphatase type 2B (calcineurin)-mediated, FK506-sensitive regulation of intracellular ions in yeast is an important determinant for adaptation to high salt stress conditions.

T Nakamura, Y Liu, D Hirata, H Namba, S Harada, T Hirokawa, and T Miyakawa

13. Quantitative Modeling of Chloride Conductance in Yeast TRK Potassium Transporters

Alberto Rivetta,* Clifford Slayman,* and Teruo Kuroda†*Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut; and †Department of Genomics and Applied Microbiology, Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama University, Okayama, Japan Biophys J. 2005 October; 89(4): 2412–2426. Published online 2005 July 22. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066712.

14. Sodium channels in cultured cardiac cells

A B Cachelin , J E Peyer, S Kokubun July 1, 1983 The Journal of Physiology, 340, 389-401.

"

"