Team:NYMU-Taipei/Project/Speedy reporter

From 2010.igem.org

(→aptamer) |

(→References) |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

=<font color=blue>References</font>= | =<font color=blue>References</font>= | ||

| + | *Barnard, E., McFerran, N.V., Trudgett, A., Nelson, J., and Timson, D.J. (2008). Development and implementation of split-GFP-based bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays in yeast. ''Biochem Soc Trans'' 36, 479-482. | ||

| - | + | *Demidov, V.V., and Broude, N.E. (2006). Profluorescent protein fragments for fast bimolecular fluorescence complementation in vitro. ''Nat Protoc'' 1, 714-719. | |

| - | * | + | |

| - | * | + | *Huttelmaier, S., Zenklusen, D., Lederer, M., Dictenberg, J., Lorenz, M., Meng, X., Bassell, G.J., Condeelis, J., and Singer, R.H. (2005). Spatial regulation of beta-actin translation by Src-dependent phosphorylation of ZBP1. ''Nature'' 438, 512-515. |

| - | + | ||

| - | * | + | *Imataka, H., and Sonenberg, N. (1997). Human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) possesses two separate and independent binding sites for eIF4A. ''Mol Cell Biol'' 17, 6940-6947. |

| - | * | + | |

| - | + | *Johnstone, O., and Lasko, P. (2001). Translational regulation and RNA localization in Drosophila oocytes and embryos. ''Annu Rev Genet'' 35, 365-406. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | * | + | *Lin, A.C., and Holt, C.E. (2007). Local translation and directional steering in axons. ''EMBO J'' 26, 3729-3736. |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | *Martin, K.C., and Ephrussi, A. (2009). mRNA localization: gene expression in the spatial dimension. ''Cell'' 136, 719-730. | |

| - | * | + | |

| - | + | *Oguro, A., Ohtsu, T., Svitkin, Y.V., Sonenberg, N., and Nakamura, Y. (2003). RNA aptamers to initiation factor 4A helicase hinder cap-dependent translation by blocking ATP hydrolysis. ''RNA'' 9, 394-407. | |

| - | * | + | |

| - | * | + | *Paquin, N., and Chartrand, P. (2008). Local regulation of mRNA translation: new insights from the bud. ''Trends Cell Biol'' 18, 105-111. |

| - | + | ||

| - | * | + | *Remy, I., and Michnick, S.W. (2007). Application of protein-fragment complementation assays in cell biology. ''Biotechniques'' 42, 137, 139, 141 passim. |

| + | |||

| + | *Story, R.M., Li, H., and Abelson, J.N. (2001). Crystal structure of a DEAD box protein from the hyperthermophile Methanococcus jannaschii. ''Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A'' 98, 1465-1470. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *Valencia-Burton, M., McCullough, R.M., Cantor, C.R., and Broude, N.E. (2007). RNA visualization in live bacterial cells using fluorescent protein complementation. ''Nat Methods'' 4, 421-427. | ||

Revision as of 18:43, 27 October 2010

| Home | Project Overview | Speedy reporter | Speedy switch | Speedy protein degrader | Experiments and Parts | Applications | F.A.Q | About Us |

Contents |

Overview design by figure

Abstract

- Our Speedy RNA+protein reporter effectively skips protein folding when reporting, thus reducing the time for a fluorescent response.

More specific insights into molecular mechanisms and gene regulation are essential for improvement in synthetic biology. Understanding these mechanisms requires time. Our speedy reporter for reporting RNA and protein expression in a cell effectively skips protein folding when reporting -- the longest part of gene expression - thus reducing the time needed to get a fluorescence. By speeding up the reporter, in both RNA and protein, we have also speed up the exploration for rules in the biological system. We can not only generate more novel circuits but also explore gene regulations in synthetic biology.

Introduction

Recent studies of mRNA localization show that a great part of mRNA localize in specific cytoplasm position (Martin and Ephrussi, 2009). For examples, ASH1 mRNA localize at bud tip of budding yeast to allow asymmetric segregation from mother to daughter cell (Paquin and Chartrand, 2008). In the Drosophila the localization of mRNA at anterior and posterior of oocyte play an important role in the developing embryo (Johnstone and Lasko, 2001). Local translation of mRNAs in axonal growth cones helps axon navigate to it synaptic partners (Lin and Holt, 2007). β-actins mRNA localize at sites of active actins polymerization, cytoskeletal-mediate motility need mRNA translation (Huttelmaier et al., 2005). All the examples above is studies on eukaryotic system. there are a few studies of mRNA location in prokaryotic system. And most of synthetic biology designs on prokaryotic bacteria. The more basic rule of prokaryotic system we know, the more successful and speedy experiments we will have.

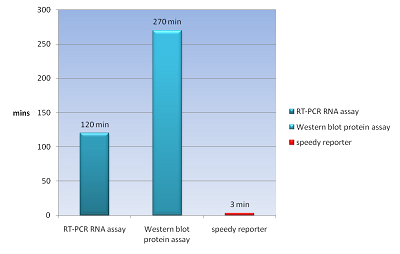

The common way to detect mRNA is RT-PCR, which can only be done in vitro but can’t in a real living cell. The common way to detect the protein is fusion a reporter protein such as GFP to report it, and the folding of GFP takes about four hours. In order to do both assay speedy and in vivo, we apply a novel technique Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation, BiFC. In our design, we need not to wait four hours for folding of GFP to detect our protein fusion GFP. We can get our signal in few minute using this method. And it also can detect the mRNA both location and quantity (Demidov and Broude, 2006). We can use this method save about fours for protein assay and two hours for mRNA assay (Fig.1).

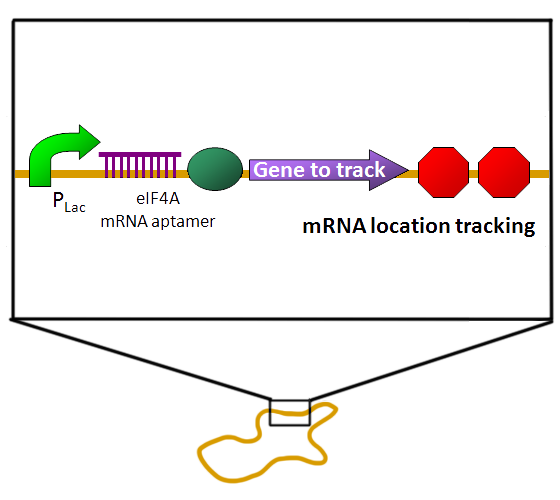

| BiFC is developed base on the technique Protein-fragment Complement Assay, PCA (Barnard et al., 2008; Demidov and Broude, 2006). Protein-protein interactions coupled to refolding of a pair of split enzymes in the PCA technique. The enzyme used in PCA has it activity only when two split parts reconstruct together. The activities of enzyme act as a detector of protein-protein interaction (Remy and Michnick, 2007). While the BiFC technique use split fluorescent protein instead of split enzyme in the PCA. The split form of fluorescent protein alone has no fluorescence. Fluorescence appears when two split parts reassembly together immediately in few minutes. For mRNA detection, we design a system differ from BiFC’s protein-protein interaction to RNA-protein interaction. Where a GFP is split into two inactive parts and fused with two parts of the split-eIF4A protein, a kind of RNA binding protein. On the other hand, we designed an mRNA aptamer that the eIF4A protein can bind to. EGFP will fluoresce through the interaction of split eIF4A and its corresponding aptamer. Using this method, we can immediately detect mRNA quantity and location in vivo. For protein detection, we design another system of BiFC which RFP is splits into two inactive parts and fused with two parts of antibody light chain and heavy chain. And then we fused the antigen to target protein. When target protein fusion antigen appears, the light chain and heavy chain combine with antigen. And then split RFPs reconstruct and fluoresce. |

Design

- Our circuit design:

- EGFP-eIF4A system / RNA aptamer on plasmid pSB1C3.

EGFP/ERFP + split eIF4A

- split GFP/RFP

We split the EGFP/ERFP into two parts, the larger N-terminal part and the smaller C-terminal part. The N-terminal part contains performed chromophore and has a very weak fluorescence that is hard to detect. Only when it combines with the small C-terminal fragment, does the fluorescence become very bright. When both parts combine, we can detect the location of the mRNA and protein. The probability that these two split parts of EGFP/ERFP can fit together without an outside force is very low, thus ther are few false-positive signal (Demidov and Broude, 2006).

- eIF4A

eIF4A is an abbreviation for eukaryotic initiation factor 4A. It is a member of the DEAD-box RNA helicase protein family eIF4F (Oguro et al., 2003), and the DEAD-box is one of the largest subgroups of the RNA helicase protein family (Story et al., 2001).

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) is a protein consists of eIF4A, eIF4E, and eIF4G. eIF4A is a helicase need ATP to unwind the secondary structure of mRNA untranslated region and make ribosome binds easier. eIF4E can binds to the cap structure of mRNA. eIF4G is like a scaffold of eIF4A and eIF4E helping them coordinate their functions. Without eIF4E and eIF4G the eIF4A alone exist much lower RNA helicase activity than complete eIF4F (Imataka and Sonenberg, 1997).

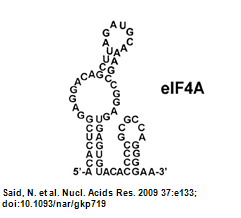

eIF4A aptamer

- What is eIF4A aptamer?

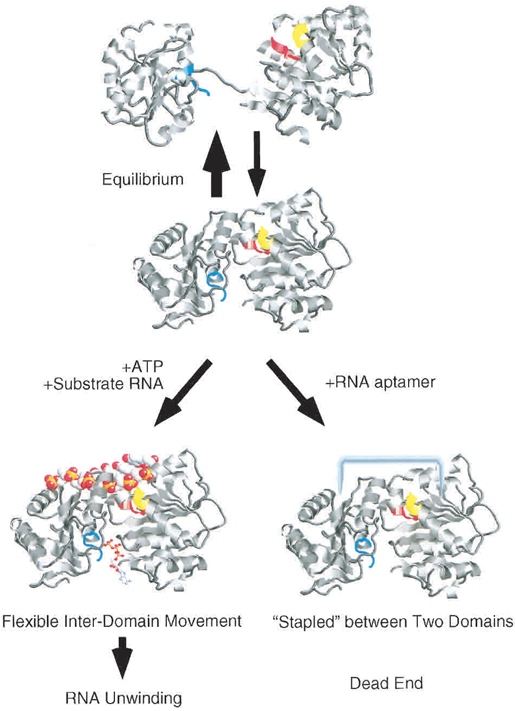

The eIF4A aptamer that we used has a high affinity for complete eIF4A protein. Its affinity is strong enough that it will combine the split eIF4A(described above) into a complete eIF4A protein. In the presence of eIF4A aptamer, ATP hydrolysis is inhibited and the RNA substrate which binds onto the eIF4A cannot unwind.

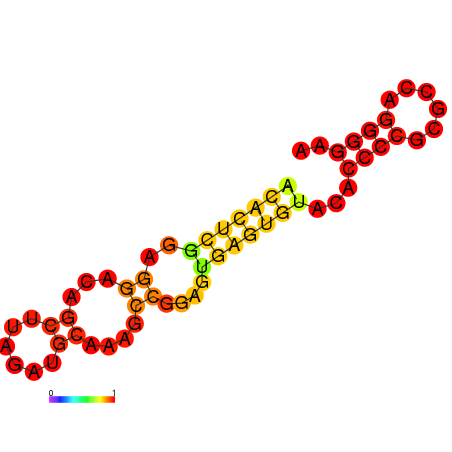

It is proposed that the eIF4A structure is in a equilibrium between dumbbell-shaped structure and compact struction in solution. In the presence of ATP and absence of RNA aptamer, the equilibrium will be shifted into the dumbbell-shaped eIF4A (Fig.2). In the opposite condition, the equilibrium will be shifted into the compact one (Valencia-Burton et al., 2007).

- eIF4A aptamer Secondary structure:

- Structure predicted by RNAfold:

- Structure of eIF4A aptamer:

Material and Methods

We constructed two devices by the parts below:

- RNA reporter consists of :

- EGFP

- ERFP

- eIF4A

- fusion parts

- aptamer

- protein reporter consists of :

- split RFP

- split peptide adaptor

RNA reporter device

GFP

- Splitting the GFP([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E0040 BBa_E0040]) at 157th and 158th amino acid which was generated by iGEM07_Davidson_Missouri's [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715019 BBa_I715019] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715020 BBa_I715020]. The A-part split is the same as [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715019 BBa_I715019] , but the B-part is one base different from [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715020 BBa_I715020]. After the splitting, we both add linkers in back of A-part split and B-part split via PCR. By doing so, we can get well-prepared for the next step.

RFP

- Splitting RFP ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E1010 BBa_E1010]) at 154th and 155th amino acid used by iGEM07_Davidson_Missouri's [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715022 BBa_I715022] and [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715023 BBa_I715023]. The A-part split is the same as [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715022 BBa_I715022], but the B-part has one base difference from [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I715023 BBa_I715023]. After the splitting, we both add linkers in back of A-part split and B-part split via PCR. By doing so, we can get well-prepared for the next step.

eIF4A

- We take the protein coding region from the [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NM_144958 eIF4A mRNA transcript sequence from Mouse (from NCBI)] and found that it had 2 PstI cutting sites. For fear that our PstI cutting enzyme would cut the wrong place, we mutated the two PstI cutting sites.After mutation, we split eIF4A ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K411100 BBa_K411100]) at 215&216th amino acid.

- The template of eIF4A on a [http://genome-www.stanford.edu/vectordb/vector_descrip/COMPLETE/PGEX4T1.SEQ.html pGEX-4TI vector] was kindly provided by Pro.C.Proud.

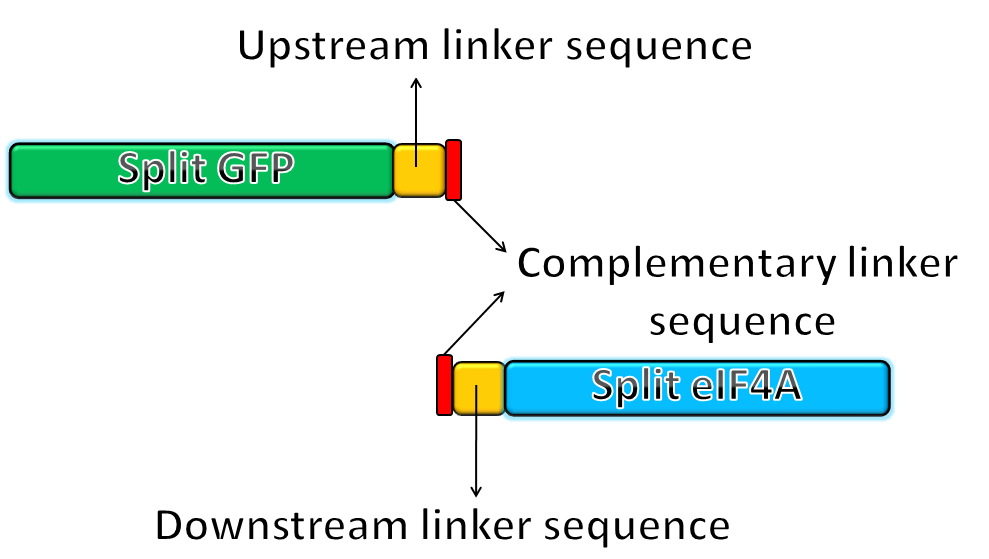

Fusion parts

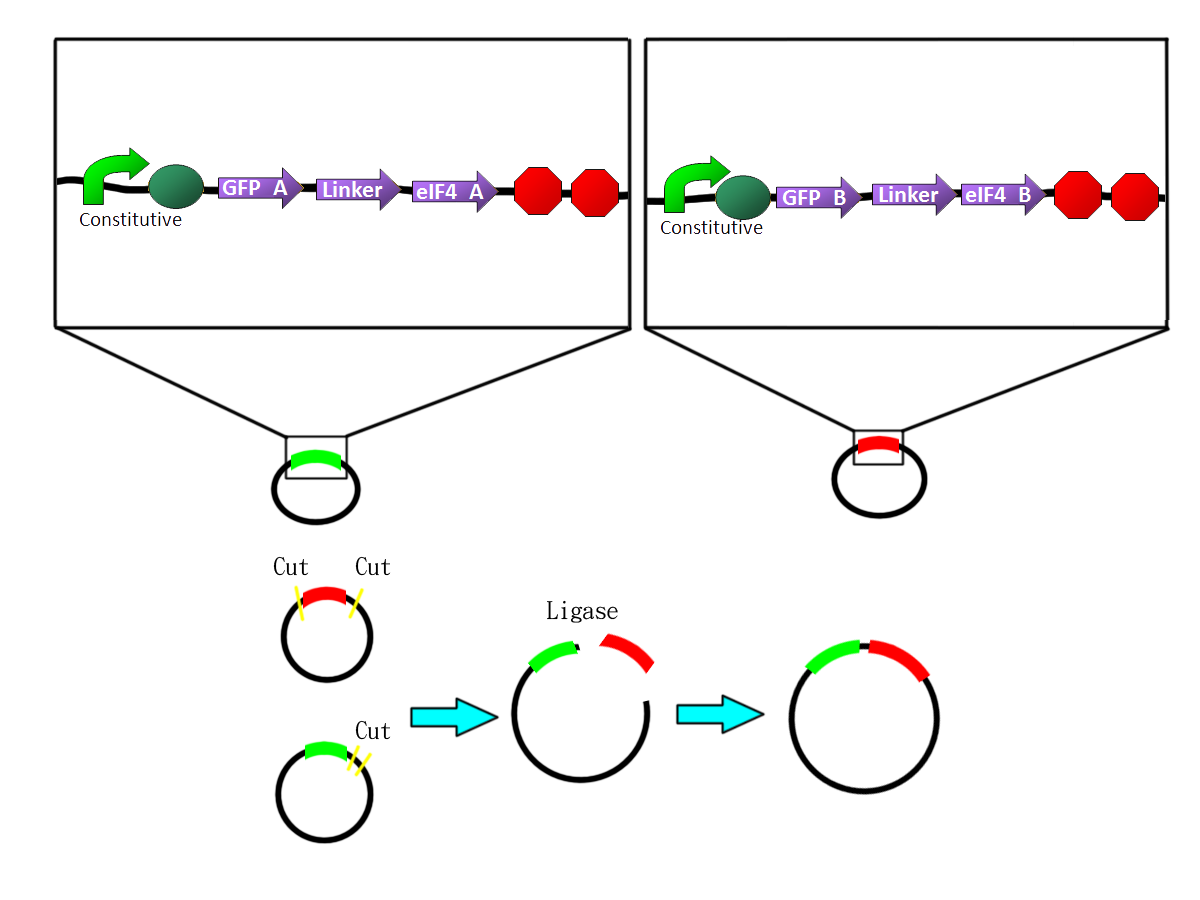

GFP fusion system

- We fused the split-GFP part with split-eIF4A part via PCR to get two sequences: split-GFP-A+linker+split-eIF4A-A([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K411101 BBa_K41111])and split-GFP-B+linker+split-eIF4A-B([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K411102 BBa_K11102]) We then added terminators in the back of both sequences and inserted them into one plasmid.

|

The picture shows the templates of PCR potocol. The split-GFP part and split-eIF4A part both have complementary linker sequences, which will anneal during the PCR process. |

RFP fusion system

- Similarly, we fused the split-RFP part with split-eIF4A part via PCR to get two sequences:split-RFP-A+linker+split-eIF4A-A ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K411103 BBa_K411103])and split-GFP-B+linker+split-eIF4A-B([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K411104 BBa_K411104])

aptamer

- We performed PCR to get the required aptamer based on sequence showed in the paper (Valencia-Burton et al., 2007).

We first designed primers by adding a prefix in the front of the aptamer sequence and a suffix at the end of the aptamer sequence. We digested the aptamer with Xbal&PstI cutting enzymes and the pLac with Spal&PstI cutting enzymes. We then used ligase to join them together.

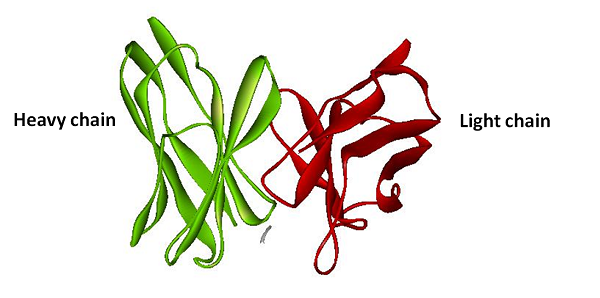

protein reporter device

The basic principle of protein reporter device is the same as the RNA reporter. First, we fuse split RFP with anti-His tag antibody light chain and heavy chain. Second, we fuse His-tag sequence with our target protein sequence. Once our target protein sequence being tranlated the anti-His tag antibody will binding on the Histidine tag. And then with combining of the heavy chain and the light chain, The split ERFP reconstruct and make brightly fluorescence.

Advantages

1.Tests the promotor strength in a speedy way.

- Conventionally, inducible promoter strength is tested by a reporter gene (e.g. GFP) downstream from the promoter. To do know, one needs to wait for protein folding (four hours for GFP). In our design, we can test the promoter strength at the mRNA level and only needs 3 min for the split GFP to reconstitute into functional protein.

- A strong promoter will result in more RNA aptamers. The more RNA aptamer, the more our split GFP will combine to emit a stronger fluorescence. With a weaker promoter, less RNA aptamers are created, and thus, less split GFP will combine to fluoresce.

2.Locates specific genes or chemicals (such as heavy metals)

- Similar to the promoter testing, we can use the inducible promoter whose inducers are heavy metals(e.g. As or Zn). When these heavy metals is present, the promoter will be induced and transcribed into mRNA aptamer. With our GFP reporter, it will bind to the RNA aptamer and emit fluorescence. With this we can know that the quantity of heavy metal pollution in that environment.

3.Helps other teams test their biobricks.

4.Shows mRNA positioning in a sigle cell.

- By understanding the RNA localization in a cell, we can learm more about how gene regulation works in a cell. And by understanding more about the precise gene regulations, we can explore more about the design rules in synthetic biology.

5.Measures the quantity of the mRNA.

6.View the temporal dynamics in a cell

7.Speeds up the reporting progress.

- With our reporting system, we can produce fluorescence in or RNA or protein assya in roughly 3 minutesWe can do a protein assay or mRNA assay in our speedy reporter system. It is faster than the conventional method RT-PCR for mRNA which needs about two hours and western blot for protein quantitative analysis which requires about 4.5 hours.

- The split GFP is a constitutive protein in the cell. Once the RNA aptamer is transcribed, the split GFP linked with eIF4A will bind to the RNA aptamer due to its high affinity. We skip the translation process due to the already-generated GFP.

References

- Barnard, E., McFerran, N.V., Trudgett, A., Nelson, J., and Timson, D.J. (2008). Development and implementation of split-GFP-based bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays in yeast. Biochem Soc Trans 36, 479-482.

- Demidov, V.V., and Broude, N.E. (2006). Profluorescent protein fragments for fast bimolecular fluorescence complementation in vitro. Nat Protoc 1, 714-719.

- Huttelmaier, S., Zenklusen, D., Lederer, M., Dictenberg, J., Lorenz, M., Meng, X., Bassell, G.J., Condeelis, J., and Singer, R.H. (2005). Spatial regulation of beta-actin translation by Src-dependent phosphorylation of ZBP1. Nature 438, 512-515.

- Imataka, H., and Sonenberg, N. (1997). Human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) possesses two separate and independent binding sites for eIF4A. Mol Cell Biol 17, 6940-6947.

- Johnstone, O., and Lasko, P. (2001). Translational regulation and RNA localization in Drosophila oocytes and embryos. Annu Rev Genet 35, 365-406.

- Lin, A.C., and Holt, C.E. (2007). Local translation and directional steering in axons. EMBO J 26, 3729-3736.

- Martin, K.C., and Ephrussi, A. (2009). mRNA localization: gene expression in the spatial dimension. Cell 136, 719-730.

- Oguro, A., Ohtsu, T., Svitkin, Y.V., Sonenberg, N., and Nakamura, Y. (2003). RNA aptamers to initiation factor 4A helicase hinder cap-dependent translation by blocking ATP hydrolysis. RNA 9, 394-407.

- Paquin, N., and Chartrand, P. (2008). Local regulation of mRNA translation: new insights from the bud. Trends Cell Biol 18, 105-111.

- Remy, I., and Michnick, S.W. (2007). Application of protein-fragment complementation assays in cell biology. Biotechniques 42, 137, 139, 141 passim.

- Story, R.M., Li, H., and Abelson, J.N. (2001). Crystal structure of a DEAD box protein from the hyperthermophile Methanococcus jannaschii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 1465-1470.

- Valencia-Burton, M., McCullough, R.M., Cantor, C.R., and Broude, N.E. (2007). RNA visualization in live bacterial cells using fluorescent protein complementation. Nat Methods 4, 421-427.

"

"