Team:ETHZ Basel/Biology/Molecular Mechanism

From 2010.igem.org

(→References) |

(→Chemotaxis network: Che proteins) |

||

| (136 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

= Molecular Mechanism = | = Molecular Mechanism = | ||

| - | |||

| - | + | == Chemotaxis network: Che proteins == | |

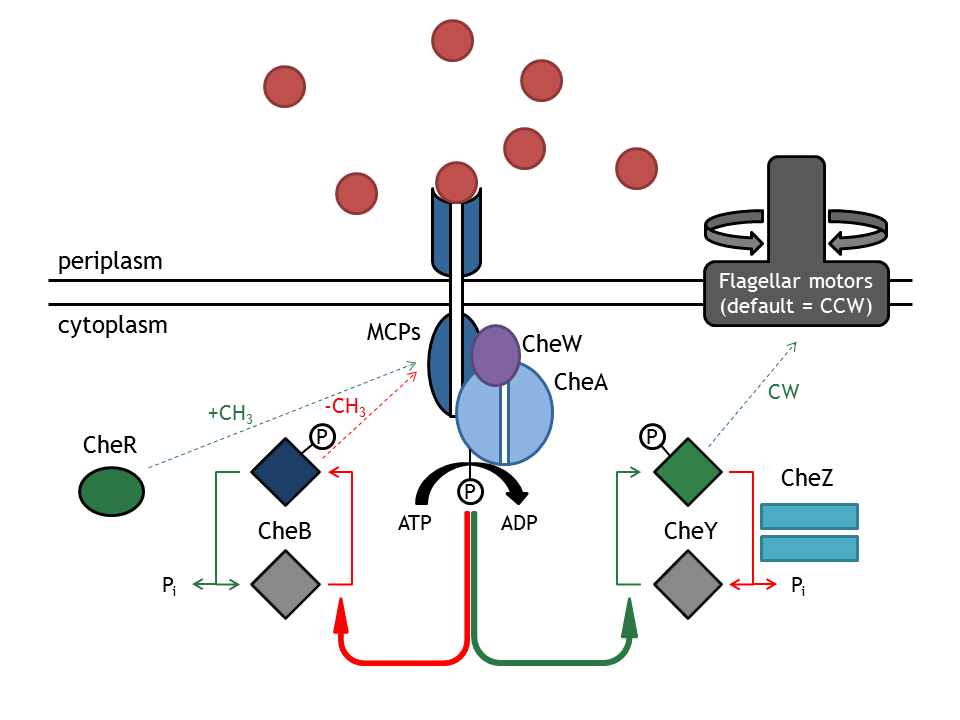

| - | == | + | [[Image:ETHZ_Basel_chemotactical_network.png|thumb|400px|'''Schematic overview of the chemotaxis pathway.''' MCPs refers to the membrane receptor proteins and Che to the intracellular chemotaxis proteins.]] |

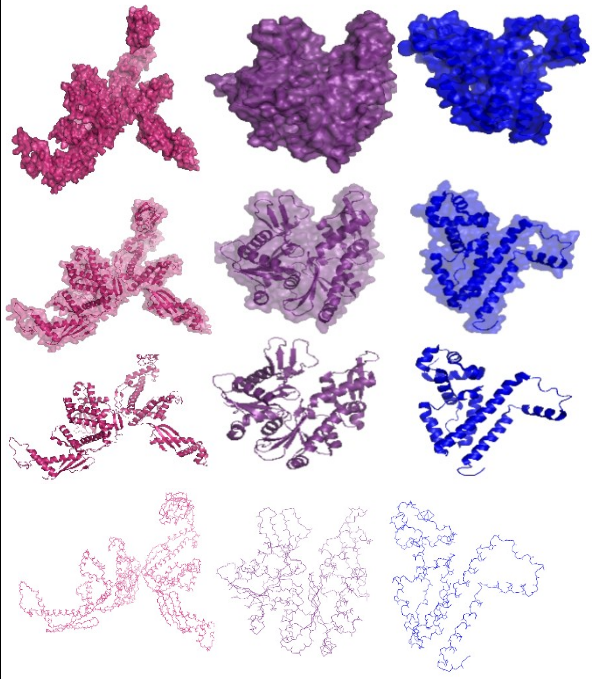

| + | [[Image:ETHZ_Basel_CHE proteins.png|thumb|400px|'''Meet the Che's!''' An overview of the Che proteins used to build the E. lemming. Color code: CheR=red, CheB=yellow, CheY=orange, CheW=cyan, CheA=green, CheY/CheZ complex=purple. On the right, the surface structure is shown, on the left the tertiary and quartenary structure. Functional subdomains, ligands and side chains not shown, not sized relatively to each other [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[9]]].]] | ||

| - | + | The '''chemotaxis signaling network''' is required for the directed movement of bacteria, as a response to changes in the extracellular concentration of chemoattractants or chemorepellents. The concentration change can be seen as an input signal, which is subsequently integrated and converted into a response. The change in direction (or more specifically, the change in the angular momentum) can therefore be understood as a function of extracellular inputs, such as a chemical gradient or a light pulse. The two types of movement that the bacterium can employ are '''tumbling''' (i.e. change in angle and no change in spatial coordinates), occurring when the bacterium does not sense an increase in attractant concentration and '''directed movement''' ( i.e. change in position and slight change in angle), occurring when the attractant concentration is sensed as increasing. Those stimuli are then administered in the chemotaxis network and this produces an output, preferably in such a way, that the bacterium is directed right to the attractant or far away from the repellent. In ''E. coli'', these two types of movements can be mechanistically distinguished by their different rotation directions of the flagellar Mot (motor) proteins (clockwise: tumbling; counter-clockwise: directed movement). | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | This network consists of membrane-associated proteins (methyl accepting chemotaxis proteins: MCPs) and soluble (intracellular) proteins (Che) as signal transducers and receptors. MCPs can sense even a minimal change in concentration (input) and transduce this information unit to the respective proteins '''CheW''' and '''CheA''', which are located inside the cell. The autophosphorylation of CheA mediated by the MCPs is the key step in tumbling induction in response to increased repellent or decreased attractant concentration. The methylation state of the MCPs is influenced by the methyltransferase '''CheR''' (transfers a methylgroup to a protein) and the Demethylase '''CheB'''(cleaves a methyl group off a protein). CheA phosphorylates CheY which then freely diffuses (as CheYp) through the cytoplasm to the flagellar motor protein FliM, where it induces tumbling as a response. The phosphatase '''CheZ''' regulates the signal termination via dephosphorylation of CheYp (the p stands for the phosphorylated form of CheY). | |

| - | + | CheY and CheYp, respectively, act as a '''mechanistic switch''' between the tumbling state and the directed movement. This molecular behavior of the protein can be utilized for artificially introducing switching between those two states. When browsing the following pages, you will be introduced to the implementation of our wish, to even use this switch remotely! | |

| - | + | The [https://2010.igem.org/Team:ETHZ_Basel/Modeling/Movement movement model] developed by our team simulates the motility of E. coli, by probabilistically switching between the two states: directed movement and tumbling, as a function of the CheYp concentration received as input from the [https://2010.igem.org/Team:ETHZ_Basel/Modeling/Chemotaxis chemotaxis pathway model]. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

== Light activated system: PhyB-Pif3 == | == Light activated system: PhyB-Pif3 == | ||

| - | + | In plants and some bacteria, members of the phytochrome family (photoreceptors) regulate phototaxis, photosynthesis and production of protective pigments in response to light stimuli. The chromophore is encoded in the N-terminal domain of the protein [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[1]]]. | |

| - | In plants and some bacteria, members of the | + | There are two major types of Phytochromes, type I (PhyA) and type II ('''PhyB''' and PhyC) [2, p.142]. Both exist in a '''biologically inactive form Pr absorbing red light''' and an '''active configuration Pfr which absorbs far-red light''', using a covalently attached tetraphyrrole chromophore for light absorption [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[5]]]. The interconversion between these two states takes only milliseconds [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[3]]]. While the Pr form is very stable (half live of about 100h), the Pfr form, in contrast, is quickly degraded (type I half-life between 30min and 2h, type II half live around 8h) [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[2]]] |

| - | There are two | + | |

| - | Light-switchable gene systems | + | Light-switchable gene systems often are based on the '''Phytochrome interacting factor Pif3''', a basic protein with a helix-loop-helix motif, which switches on light-induced gene expression. The N-Terminus of Pif3 selectively binds the Prf form of the phytochrome and rapidly dissociates in response to reconversion to the Pr state [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[3]]]. |

| - | For the design of a light-activated system in Bacteria one has to consider that chromophores such as phycocyanobilin PBS | + | For the design of a light-activated system in Bacteria, one has to consider that chromophores such as phycocyanobilin PBS do not naturally occur; therefore, in order to start expression of light-inducable genes, chromophores either have to be added to the medium or two genes for its biosynthesis (starting from heme) have to be introduced to the prokaryotic genome. [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[4]]]. Furthermore, attention must be paid, because phyotochromes in their Prf state in plants can form sequesters in the timescale of seconds! [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[2]]]. |

| - | == | + | == Spatial localization in a bacterial cell: Anchor proteins TrigA, MreB and TetR== |

| + | {| border="0" align="center" | ||

| + | |- valign="top" -halign="center" | ||

| + | |[[Image:ETHZ_Basel_biology_anchor_tet.png|thumb|center|300px|'''Spatial localization in a bacterial cell using Tet:''' Tet repressor bound to it's operator on a high copy plasmid.]] | ||

| + | |[[Image:ETHZ_Basel_biology_anchor_ribosome.png|thumb|center|300px|'''Spatial localization in a bacterial cell using Ribosomes:''' Ribosome binding domain of trigger factor bound to the large subunit of the ribosome.]] | ||

| + | |[[Image:ETHZ_Basel_biology_anchor_mreb.png|thumb|center|300px|'''Spatial localization in a bacterial cell using MreB protofilament.''']] | ||

| + | |} | ||

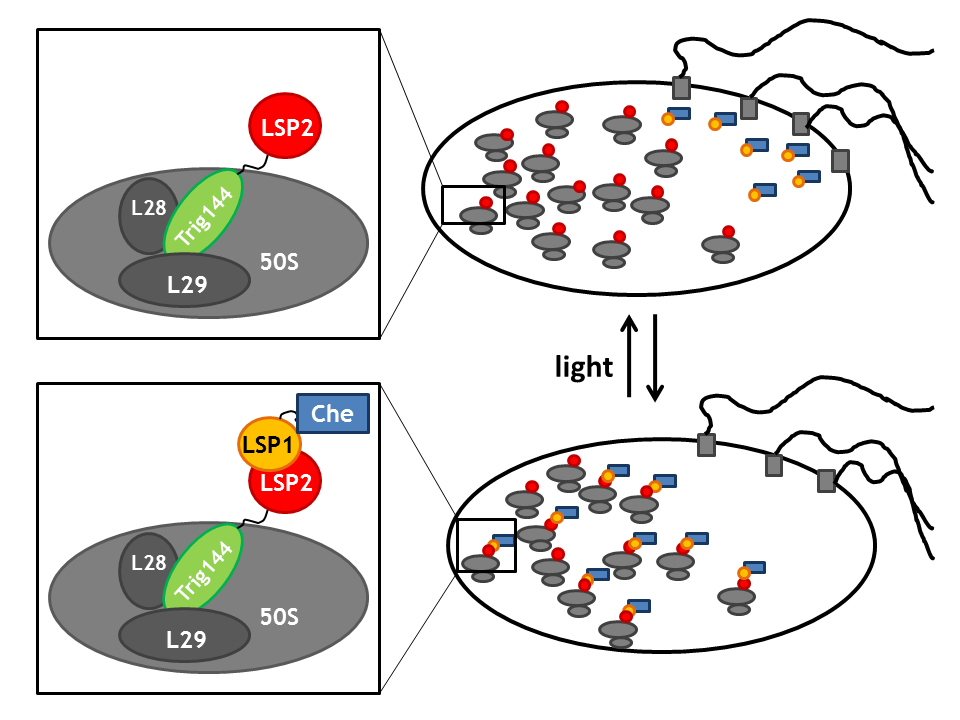

| - | + | By spatial localization of one Che protein (Che binds to a specific cellular component and is anchored), the tumbling frequency of a bacterial cell can be manipulated. We decided to focus on three different anchors that will be fused to one light sensitive protein LSP, which dimerizes upon light stimulus with it's LSP partner that is bound to a Che-protein. Therefore, upon light signal, the Che-protein is localized in the cell. | |

| - | [ | + | The three anchors are: |

| + | *the '''tetracyclin repressor tetR''', which binds to it's operator tetO (present on a high copy vector in the cell) [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[6]]] | ||

| + | *the ribosome binding domain of the '''trigger factor trigA''' that binds to the large subunit of the ribosome [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[7]]]. | ||

| + | *The '''prokaryotic actin homologue MreB''' which anchors the Che protein to the cell wall [[Team:ETHZ_Basel/Biology/Molecular_Mechanism#References|[8]]]. | ||

| - | + | Upon a light stimulus, the light-sensitive proteins LSPs dimerize (photodimerization) and therefore spatially localize the Che-protein. This greatly affects the activity of the Che downstream partners as Che is then no longer available for signal transduction (the intracellular concentration of free Che drastically decreases). '''Thus, these anchors enable us to induce and repress the directed movement or tumbling of the flagellar machine'''. | |

| - | |||

| - | [ | + | [[Image:ETHZ_Basel_TrigA, MreB and TetR.png|thumb|center|500px|'''Watch TrigA, MreB and tetR getting naked!''' The A-terminal ribosome-binding domain of the ''E. coli'' trigger factor (a chaperone, which helps in co-translational protein folding), the prokaryotic actin homologue MreB (a structural protein, which forms F-actin-like strands and is crucial for cell form determination) and the bacterial tetracycline repressor TetR (the resistance protein TetA, found in gram-negative bacteria is responsible for tetracycline efflux) are used as building blocks of E. lemming's chemotaxis pathway. TrigA=pink, MreB=purple, tetR=blue [9].]] |

| - | [ | + | == References == |

| - | + | [1] [http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v20/n10/abs/nbt734.html Sato, Hug, Tepperman and Quail: A light-switchable gene promoter system. Nature Biotechnology. 2002; 20.] | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | [ | + | [2] [http://books.google.ch/books?hl=de&lr=&id=BfnKE98pTXMC&oi=fnd&pg=PR8&dq=Photomorphogenesis+in+plants&ots=23AEp7R78F&sig=9SXToaZr0ie6w6ooQb_9rs5IFrM#v=onepage&q&f=false Kendrick and Kronenberg: Photomorphogenesis in plants. Kluwer academic publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 2nd edition, 1994.] |

| - | [ | + | [3] [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TCW-47BX7M3-1&_user=791130&_coverDate=02/28/2003&_rdoc=2&_fmt=high&_orig=browse&_origin=browse&_zone=rslt_list_item&_srch=doc-info(%23toc%235181%232003%23999789997%23384698%23FLA%23display%23Volume)&_cdi=5181&_sort=d&_docanchor=&_ct=10&_acct=C000043379&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=791130&md5=8b3d8707b40c1250ede257b97c0346fe&searchtype=a Keyes and Mills: Inducible systems see light. Trends in Biotechnology. 2003; 21:2.] |

| - | + | ||

| + | [4] [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v438/n7067/abs/nature04405.html Levskaya, Chevalier, Tabor, Simpson, Lavery, Levy, Davidson, Scourast, Ellington, Marcotte and Voigt: Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature Brief Communications. 2005, 438.] | ||

| + | [5] [http://www.springerlink.com/content/f602r72767124602/ M.J. Tindall, S.L. Porter, P.K. Maini, G. Gaglia, J.P. Armitage. Overview of Mathematical Approaches Used to Model Bacterial Chemotaxis I: The Single Cell. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2008) 70: 1525–1569.] | ||

| + | [6] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1751-7915.2007.00001.x/full Bertram and Hillen: The application of Tet repressor in prokaryotic gene regulation and expression. Microbial Biotechnology. 2008; 1:1.] | ||

| + | [7] [http://www.jbc.org/content/272/35/21865.full Hesterkamp, Deuerling and Bukau: The Amino-terminal 118 amino acids of Escherichia coli Trigger factor constitute a domain that is necessary and sufficient for binding to ribosomes. The Journal of Biologcial Chemistry. 1997; 272:35.] | ||

| + | [8] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04367.x/full Kruse, Bork-Jensen and Gerdes: The morphogenetic MreBCD proteins of Escherichia coli form an essential membrane-bound complex. Molecular Microbiology. 2005;55:1.] | ||

| - | + | [9] [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/home/home.do: RSCB Protein Data Bank and respective publications:] | |

| + | [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1A2O: CheB_1A20] | ||

| + | [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1AF7: CheR_1AF7] | ||

| + | [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=3GWG: CheY_3GWG] | ||

| + | [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=2HO9: CheW_2HO9] | ||

| + | [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1I5D: CheA_1I5D] | ||

| + | [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1I5D: CheY/CheZ complex_1I5D] | ||

| + | [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1JCE: MreB_1JCE] | ||

| + | [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=2XB5: TetR_2XB5] | ||

| + | [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1W26: TrigA_1W26] | ||

Latest revision as of 03:21, 28 October 2010

Molecular Mechanism

Chemotaxis network: Che proteins

The chemotaxis signaling network is required for the directed movement of bacteria, as a response to changes in the extracellular concentration of chemoattractants or chemorepellents. The concentration change can be seen as an input signal, which is subsequently integrated and converted into a response. The change in direction (or more specifically, the change in the angular momentum) can therefore be understood as a function of extracellular inputs, such as a chemical gradient or a light pulse. The two types of movement that the bacterium can employ are tumbling (i.e. change in angle and no change in spatial coordinates), occurring when the bacterium does not sense an increase in attractant concentration and directed movement ( i.e. change in position and slight change in angle), occurring when the attractant concentration is sensed as increasing. Those stimuli are then administered in the chemotaxis network and this produces an output, preferably in such a way, that the bacterium is directed right to the attractant or far away from the repellent. In E. coli, these two types of movements can be mechanistically distinguished by their different rotation directions of the flagellar Mot (motor) proteins (clockwise: tumbling; counter-clockwise: directed movement).

This network consists of membrane-associated proteins (methyl accepting chemotaxis proteins: MCPs) and soluble (intracellular) proteins (Che) as signal transducers and receptors. MCPs can sense even a minimal change in concentration (input) and transduce this information unit to the respective proteins CheW and CheA, which are located inside the cell. The autophosphorylation of CheA mediated by the MCPs is the key step in tumbling induction in response to increased repellent or decreased attractant concentration. The methylation state of the MCPs is influenced by the methyltransferase CheR (transfers a methylgroup to a protein) and the Demethylase CheB(cleaves a methyl group off a protein). CheA phosphorylates CheY which then freely diffuses (as CheYp) through the cytoplasm to the flagellar motor protein FliM, where it induces tumbling as a response. The phosphatase CheZ regulates the signal termination via dephosphorylation of CheYp (the p stands for the phosphorylated form of CheY).

CheY and CheYp, respectively, act as a mechanistic switch between the tumbling state and the directed movement. This molecular behavior of the protein can be utilized for artificially introducing switching between those two states. When browsing the following pages, you will be introduced to the implementation of our wish, to even use this switch remotely!

The movement model developed by our team simulates the motility of E. coli, by probabilistically switching between the two states: directed movement and tumbling, as a function of the CheYp concentration received as input from the chemotaxis pathway model.

Light activated system: PhyB-Pif3

In plants and some bacteria, members of the phytochrome family (photoreceptors) regulate phototaxis, photosynthesis and production of protective pigments in response to light stimuli. The chromophore is encoded in the N-terminal domain of the protein [1]. There are two major types of Phytochromes, type I (PhyA) and type II (PhyB and PhyC) [2, p.142]. Both exist in a biologically inactive form Pr absorbing red light and an active configuration Pfr which absorbs far-red light, using a covalently attached tetraphyrrole chromophore for light absorption [5]. The interconversion between these two states takes only milliseconds [3]. While the Pr form is very stable (half live of about 100h), the Pfr form, in contrast, is quickly degraded (type I half-life between 30min and 2h, type II half live around 8h) [2]

Light-switchable gene systems often are based on the Phytochrome interacting factor Pif3, a basic protein with a helix-loop-helix motif, which switches on light-induced gene expression. The N-Terminus of Pif3 selectively binds the Prf form of the phytochrome and rapidly dissociates in response to reconversion to the Pr state [3].

For the design of a light-activated system in Bacteria, one has to consider that chromophores such as phycocyanobilin PBS do not naturally occur; therefore, in order to start expression of light-inducable genes, chromophores either have to be added to the medium or two genes for its biosynthesis (starting from heme) have to be introduced to the prokaryotic genome. [4]. Furthermore, attention must be paid, because phyotochromes in their Prf state in plants can form sequesters in the timescale of seconds! [2].

Spatial localization in a bacterial cell: Anchor proteins TrigA, MreB and TetR

By spatial localization of one Che protein (Che binds to a specific cellular component and is anchored), the tumbling frequency of a bacterial cell can be manipulated. We decided to focus on three different anchors that will be fused to one light sensitive protein LSP, which dimerizes upon light stimulus with it's LSP partner that is bound to a Che-protein. Therefore, upon light signal, the Che-protein is localized in the cell.

The three anchors are:

- the tetracyclin repressor tetR, which binds to it's operator tetO (present on a high copy vector in the cell) [6]

- the ribosome binding domain of the trigger factor trigA that binds to the large subunit of the ribosome [7].

- The prokaryotic actin homologue MreB which anchors the Che protein to the cell wall [8].

Upon a light stimulus, the light-sensitive proteins LSPs dimerize (photodimerization) and therefore spatially localize the Che-protein. This greatly affects the activity of the Che downstream partners as Che is then no longer available for signal transduction (the intracellular concentration of free Che drastically decreases). Thus, these anchors enable us to induce and repress the directed movement or tumbling of the flagellar machine.

References

[1] [http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v20/n10/abs/nbt734.html Sato, Hug, Tepperman and Quail: A light-switchable gene promoter system. Nature Biotechnology. 2002; 20.]

[2] [http://books.google.ch/books?hl=de&lr=&id=BfnKE98pTXMC&oi=fnd&pg=PR8&dq=Photomorphogenesis+in+plants&ots=23AEp7R78F&sig=9SXToaZr0ie6w6ooQb_9rs5IFrM#v=onepage&q&f=false Kendrick and Kronenberg: Photomorphogenesis in plants. Kluwer academic publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 2nd edition, 1994.]

[3] [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TCW-47BX7M3-1&_user=791130&_coverDate=02/28/2003&_rdoc=2&_fmt=high&_orig=browse&_origin=browse&_zone=rslt_list_item&_srch=doc-info(%23toc%235181%232003%23999789997%23384698%23FLA%23display%23Volume)&_cdi=5181&_sort=d&_docanchor=&_ct=10&_acct=C000043379&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=791130&md5=8b3d8707b40c1250ede257b97c0346fe&searchtype=a Keyes and Mills: Inducible systems see light. Trends in Biotechnology. 2003; 21:2.]

[4] [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v438/n7067/abs/nature04405.html Levskaya, Chevalier, Tabor, Simpson, Lavery, Levy, Davidson, Scourast, Ellington, Marcotte and Voigt: Engineering Escherichia coli to see light. Nature Brief Communications. 2005, 438.]

[5] [http://www.springerlink.com/content/f602r72767124602/ M.J. Tindall, S.L. Porter, P.K. Maini, G. Gaglia, J.P. Armitage. Overview of Mathematical Approaches Used to Model Bacterial Chemotaxis I: The Single Cell. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2008) 70: 1525–1569.]

[6] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1751-7915.2007.00001.x/full Bertram and Hillen: The application of Tet repressor in prokaryotic gene regulation and expression. Microbial Biotechnology. 2008; 1:1.]

[7] [http://www.jbc.org/content/272/35/21865.full Hesterkamp, Deuerling and Bukau: The Amino-terminal 118 amino acids of Escherichia coli Trigger factor constitute a domain that is necessary and sufficient for binding to ribosomes. The Journal of Biologcial Chemistry. 1997; 272:35.]

[8] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04367.x/full Kruse, Bork-Jensen and Gerdes: The morphogenetic MreBCD proteins of Escherichia coli form an essential membrane-bound complex. Molecular Microbiology. 2005;55:1.]

[9] [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/home/home.do: RSCB Protein Data Bank and respective publications:] [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1A2O: CheB_1A20] [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1AF7: CheR_1AF7] [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=3GWG: CheY_3GWG] [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=2HO9: CheW_2HO9] [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1I5D: CheA_1I5D] [http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1I5D: CheY/CheZ complex_1I5D] [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1JCE: MreB_1JCE] [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=2XB5: TetR_2XB5] [http://www.pdb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1W26: TrigA_1W26]

"

"