Team:Groningen/Hydrophobins

From 2010.igem.org

(→Hydrophobins) |

(→Chaplins) |

||

| (93 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | == | + | __NOTOC__ |

| + | == Chaplins == | ||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align: justify"> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | '''Summary''' | ||

| - | + | To produce a hydrophobic coating, we want ''B. subtilis'' to form a biofilm and then express and secrete hydrophobic proteins. ''Streptomyces coelicolor'' naturally produces hydropbobic proteins called chaplins. There are different subgroups of chaplins. The proteins of one subgroup has amphithatic properties while the other subgroup consists of completely hydrophobic proteins. To test these properties in a coating we did some experiments with pure chaplins isolated out of ''S. coelicolor''. We show that by coating with chaplins we changed the hydrophobicity of a surface. Furthermore we showed that in monomeric form the chaplins have oil dispersing properties. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | === Introduction === | |

| - | + | We do not just want to make a biological coating, we would also give it special properties. We focused our attention on surface hydrophobicity since this might lead to very interesting applications. One remarkable example of surface hydrophobicity can be found in nature on [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFHcSrNRU5E lotus leafs], which are extremely water repellant. Interestingly, these leafs are self-cleansing due to this property. Surface hydrophobicity has overall been shown to have self-cleansing and anti-fouling properties (Nimittrakoolchai ''et al'' 2007) and is subject of much research. However, to obtain hydrophobic surface activity mostly chemical techniques are used. We sought to use a biological alternative. | |

| - | + | [[Image:ChpMicro.gif|thumb|right|200px|Electron microscopy picture showing S. coelicolor spores on which chaplins can be seen clearly as rod-like structures. Cover of Journal of Bacteriology, September 2008.]] | |

| - | + | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | + | <html> | |

| - | + | <object width="480" height="385"><param name="movie" value="http://www.youtube.com/v/z9GuiIUFRUk?fs=1&hl=en_US"></param><param name="allowFullScreen" value="true"></param><param name="allowscriptaccess" value="always"></param><embed src="http://www.youtube.com/v/z9GuiIUFRUk?fs=1&hl=en_US" type="application/x-shockwave-flash" allowscriptaccess="always" allowfullscreen="true" width="480" height="385"></embed></object> | |

| + | </html> | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | === Strongly hydrophobic proteins === | |

| - | share distinguishing features with the medically important | + | In order to provide our ''Bacillus subtilis'' biofilm with hydrophobic properties we have turned to highly hydrophobic proteins originating from ''Streptomyces coelicolor''. This is a soil dwelling bacterium which undergoes morphological differentiation as it goes through different stages in its life cycle, greatly resembling fungal growth. After submerged, vegetative growth aerial hyphae are formed which protrude from the moist substrate. The formation of these aerial hyphae appear to require strongly hydrophobic proteins called chaplins, which have previously been described by Claessen ''et al'' (2003) and Elliot ''et al'' (2003). |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Different chaplins, different functions === | ||

| + | There are a number of different chaplins shown in the figure below. In ''S. coelicolor'' these have specific functions in aerial growth and the transition to this phase. During submerged growth chaplins E and H are excreted and assemble at the water-air surface, drastically decreasing surface tension, allowing hyphae to break through the surface. On these forming aerial hyphae chaplins A to H assemble to form an extremely hydrophobic surface(Claessen ''et al'' 2003). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Groningen-ChaplinsStreptomcysis.png|center|600px|Showing the role of different chaplins during transition to aerial growth. Adapted from Claessen et al (2003).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Two subgroups === | ||

| + | Chaplins can be categorized into two groups. The first group consists of chaplins A to C and are about 225 amino acids in size. These large chaplins contain a signal sequence, two hydrophobic chaplin domains, a hydrophilic region and a cell wall anchor. The second group includes chaplin D to H and are with around 63 amino acids smaller than the afore mentioned chaplins. Being smaller, they only contain a signal sequence followed by a hydrophobic chaplin domain. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:ChpCartoon.jpg|center|600px|The hydrophobic chaplin domains are shown in green and are present on all chaplins. The hydrophillic region and cell wall anchor of the large chaplins are shown in blue and red, respectively.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Chaplins have the intrinsic property of assembling into rod-like structures called amyloid fibers. These fibers are very rigid and hard to break down and even resist boiling in SDS which denatures almost all natural occuring proteins. They share distinguishing features with the medically important amyloid fibers that are characteristic for many neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Huntington's, systemic amyloidosis and the prion diseases. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Physical properties === | ||

| + | [[Image:chaplins.jpg|right|300px|The normally hydrophobic surface of the petri dish on the left is made hydrophillic by coating it with purified chaplins as seen on the right.]] | ||

| + | Interestingly, purified chaplins can be used to coat normally hydrophobic surfaces such as petri dishes, rendering them hydrophilic. This is due to their amphipatic nature, being hydrophobic on one side and hydrophilic on the other. In nature though they only coat the outside of the aerial hyphae of ''S. coelicolor'' hydrophobically. We pose that the assembly on the outside of cells is important for the amyloid fibers to polymerize into the right configuration to obtain extreme hydrophobicity. This is one of the reasons we chose to express chaplins in a biofilm as opposed to coat surfaces with purified chaplins. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besides hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity we came across even another very interesting property. When in monomeric form purified chaplins appear to have very good oil dispersing properties. When in emulsion with water in oil, chaplins will interact with both water and oil dispersing the oil into the water. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Also, when monomeric, chaplins show to reduce surface tension of water which is illustrated in the figure below. It is clearly visable in the second tube from the right that monomeric chaplins flatten the meniscus at the water-oil interface. However, once assembled into polymeres, this property is lost as can be seen in the second tube from the left, which shows the same features as the tube on the far left which only contains water and oil. The tube on the far right only contained water, oil and Congo Red staining. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <html> | ||

| + | <table> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td></html>[[Image:Dispersant1GR.jpg|thumb|300px|Left to right: Water and oil; Water, oil, Congo Red staining and AssembledChaplins; Water, oil, Congo Red staining and monomeric chaplins; Water, oil and Congo Red staining.]]<html></td> | ||

| + | <td></html>[[Image:Dispersant3GR.jpg|thumb|150px|Water and oil mixed with monomeric chaplins ten minutes after shaking. Chaplins are stained with Congo Red. The oil is clearly dispersed throughout the water phase.]]<html></td> | ||

| + | <td></html>[[Image:Dispersant4GR.jpg|thumb|150px|Water and oil ten minutes after shaking, the separation of the two phases is clearly visable.]]<html></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Moreover, chaplins are extremely stable, both thermally and chemically. As an illustration, to purify them one has to turn to severe techniques like boiling in SDS and extraction with trifluoroacetic acid. Also, along the entire duration of our project – more than half a year – we did not observe any decline in the physical properties of our purified chaplins, being able to re-use the proteins over and over again. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === Chaplins in our project === | ||

| + | Overall these small proteins appear to have great potential in all kinds of applicational fields, making them very interesting additions to the parts registry as biobricks. However it was their most remarkable property – their hydrophobicity – which drew our attention to them to use them in our project. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We chose not to make all chaplins into biobricks, but to focus on chaplin C, E and H. Chaplin C is anchored in the cell wall and together with chaplins E and H coat the outside of the cell with a hydrophobic layer. Before ordering our biobricks we codon optimalized them for ''B. subtilis''. Since these proteins are not native to ''B. subtilis'' and we were unsure whether it would not degrade them with proteases we tested chaplin degradation in spent medium of ''B. subtilis''. Degradation appeared not to occur. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:ChpBB.jpg|center|600px|A cartoon showing our chaplin biobricks. In addition to the regular C chaplin we added one which has an sortase binding site (shown in yellow).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Also, we did not know whether ''B. subtilis'' would successfully secrete the C chaplin and insert it into its cell wall. So in addition to chaplins [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305001 C], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305003 E] and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305004 H] we also designed an [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305002 altered C chaplin] which has an added sortase binding motive and included a [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305005 sortase] BioBrick to our project. Sortase - originating from ''Staphylococcus aureus'' - is a well studied protein which anchors surface proteins to the cell wal (Mazmanian ''et al'' 1999). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | === References === | ||

| + | <small>Claessen, D; Rink, R; de Jong, W ''et al.'' 2003. A novel class of secreted hydrophobic proteins is involved in aerial hyphae formation in ''Streptomyces coelicolor'' by forming amyloid-like fibrils. Genes Dev '''17''' 1714-1726 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Elliot, MA; Karoonuthaisiri, N; Huang, JQ; ''et al.'' 2003 The chaplins: a family of hydrophobic cell-surface proteins involved in aerial mycelium formation in ''Streptomyces coelicolor''. Genes Dev '''17''' 1727-1740 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mazmanian, SK; Liu, G; Ton-That, H; Schneewind, O 1999. ''Staphylococcus aureus'' sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science '''285''' 760-763 | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nimittrakoolchai, O; Supothina, S 2007. Deposition of organic-based superhydrophobic films for anti-adhesion and self-cleaning applications. Journal of the European Ceramic Society '''28''' 947-952</small> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:41, 28 October 2010

Chaplins

To produce a hydrophobic coating, we want B. subtilis to form a biofilm and then express and secrete hydrophobic proteins. Streptomyces coelicolor naturally produces hydropbobic proteins called chaplins. There are different subgroups of chaplins. The proteins of one subgroup has amphithatic properties while the other subgroup consists of completely hydrophobic proteins. To test these properties in a coating we did some experiments with pure chaplins isolated out of S. coelicolor. We show that by coating with chaplins we changed the hydrophobicity of a surface. Furthermore we showed that in monomeric form the chaplins have oil dispersing properties.

Introduction

We do not just want to make a biological coating, we would also give it special properties. We focused our attention on surface hydrophobicity since this might lead to very interesting applications. One remarkable example of surface hydrophobicity can be found in nature on [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFHcSrNRU5E lotus leafs], which are extremely water repellant. Interestingly, these leafs are self-cleansing due to this property. Surface hydrophobicity has overall been shown to have self-cleansing and anti-fouling properties (Nimittrakoolchai et al 2007) and is subject of much research. However, to obtain hydrophobic surface activity mostly chemical techniques are used. We sought to use a biological alternative.

Strongly hydrophobic proteins

In order to provide our Bacillus subtilis biofilm with hydrophobic properties we have turned to highly hydrophobic proteins originating from Streptomyces coelicolor. This is a soil dwelling bacterium which undergoes morphological differentiation as it goes through different stages in its life cycle, greatly resembling fungal growth. After submerged, vegetative growth aerial hyphae are formed which protrude from the moist substrate. The formation of these aerial hyphae appear to require strongly hydrophobic proteins called chaplins, which have previously been described by Claessen et al (2003) and Elliot et al (2003).

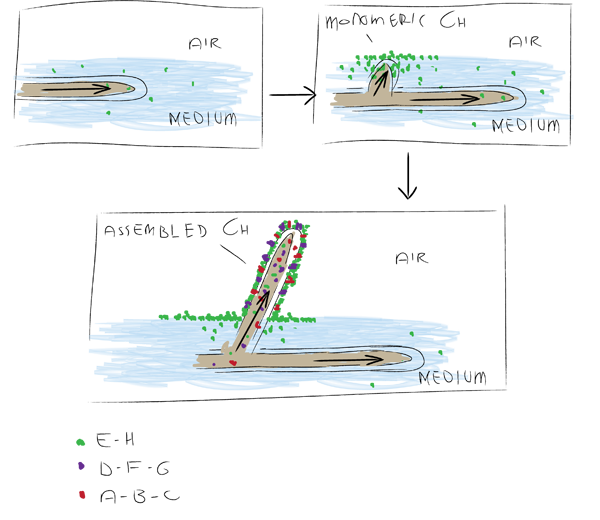

Different chaplins, different functions

There are a number of different chaplins shown in the figure below. In S. coelicolor these have specific functions in aerial growth and the transition to this phase. During submerged growth chaplins E and H are excreted and assemble at the water-air surface, drastically decreasing surface tension, allowing hyphae to break through the surface. On these forming aerial hyphae chaplins A to H assemble to form an extremely hydrophobic surface(Claessen et al 2003).

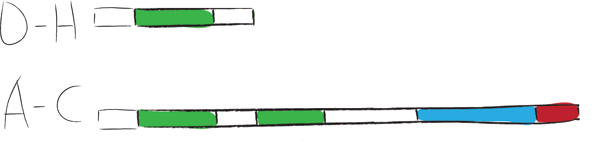

Two subgroups

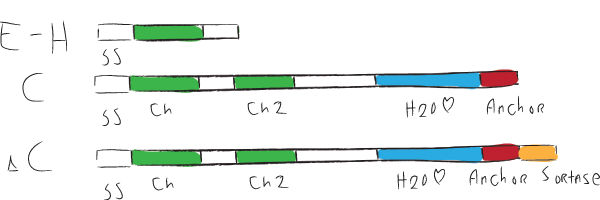

Chaplins can be categorized into two groups. The first group consists of chaplins A to C and are about 225 amino acids in size. These large chaplins contain a signal sequence, two hydrophobic chaplin domains, a hydrophilic region and a cell wall anchor. The second group includes chaplin D to H and are with around 63 amino acids smaller than the afore mentioned chaplins. Being smaller, they only contain a signal sequence followed by a hydrophobic chaplin domain.

Chaplins have the intrinsic property of assembling into rod-like structures called amyloid fibers. These fibers are very rigid and hard to break down and even resist boiling in SDS which denatures almost all natural occuring proteins. They share distinguishing features with the medically important amyloid fibers that are characteristic for many neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's, Huntington's, systemic amyloidosis and the prion diseases.

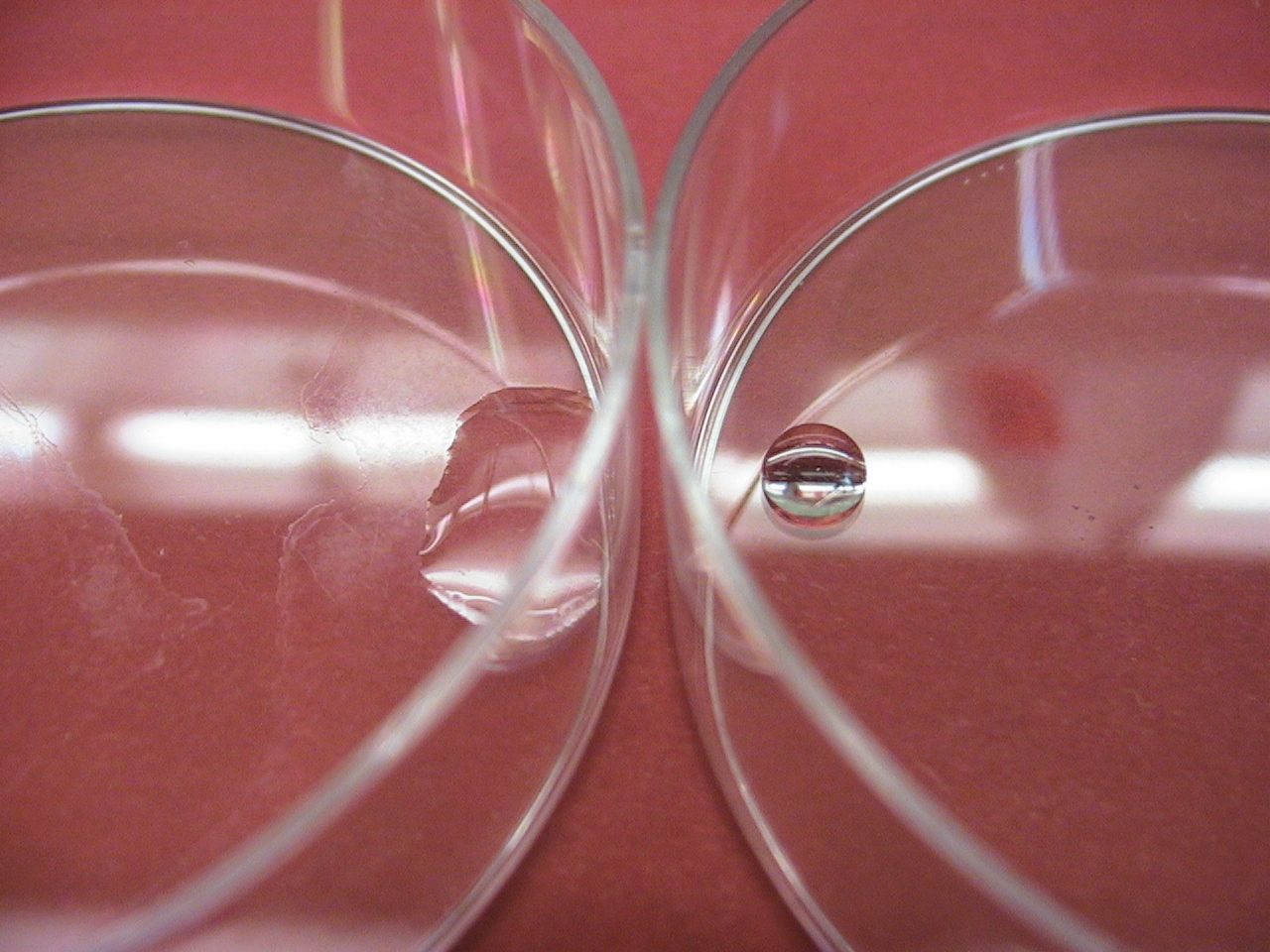

Physical properties

Interestingly, purified chaplins can be used to coat normally hydrophobic surfaces such as petri dishes, rendering them hydrophilic. This is due to their amphipatic nature, being hydrophobic on one side and hydrophilic on the other. In nature though they only coat the outside of the aerial hyphae of S. coelicolor hydrophobically. We pose that the assembly on the outside of cells is important for the amyloid fibers to polymerize into the right configuration to obtain extreme hydrophobicity. This is one of the reasons we chose to express chaplins in a biofilm as opposed to coat surfaces with purified chaplins.

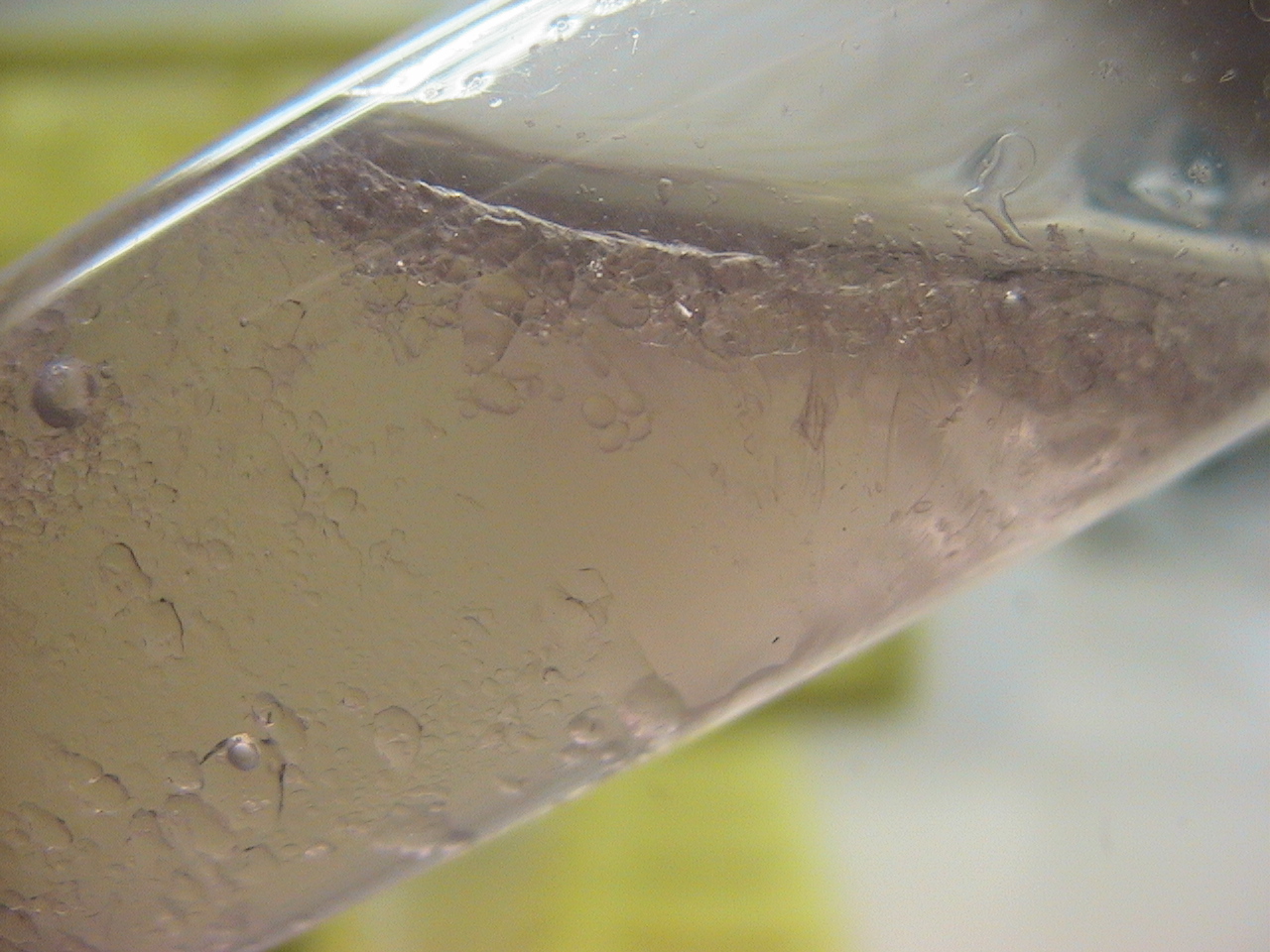

Besides hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity we came across even another very interesting property. When in monomeric form purified chaplins appear to have very good oil dispersing properties. When in emulsion with water in oil, chaplins will interact with both water and oil dispersing the oil into the water.

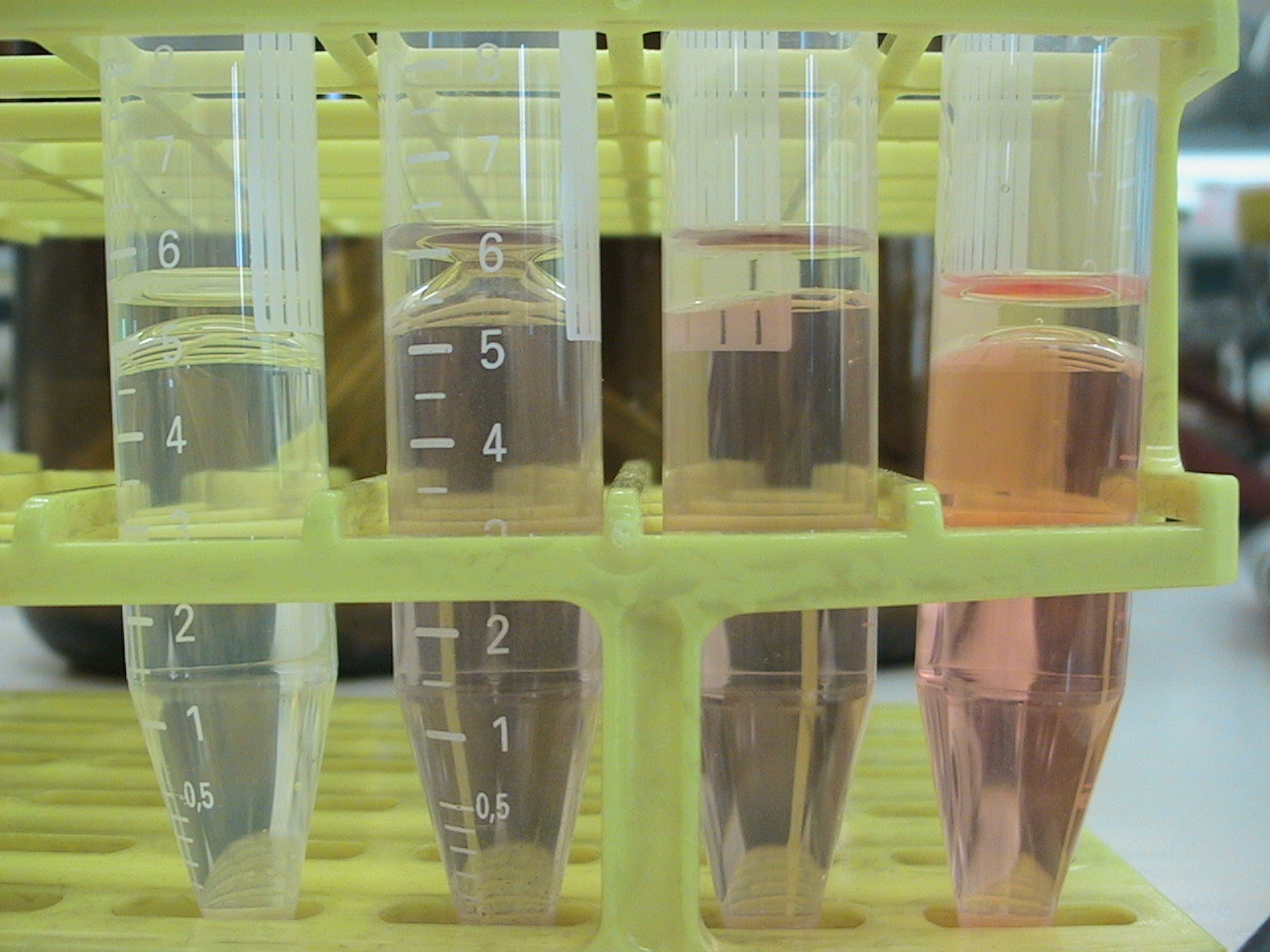

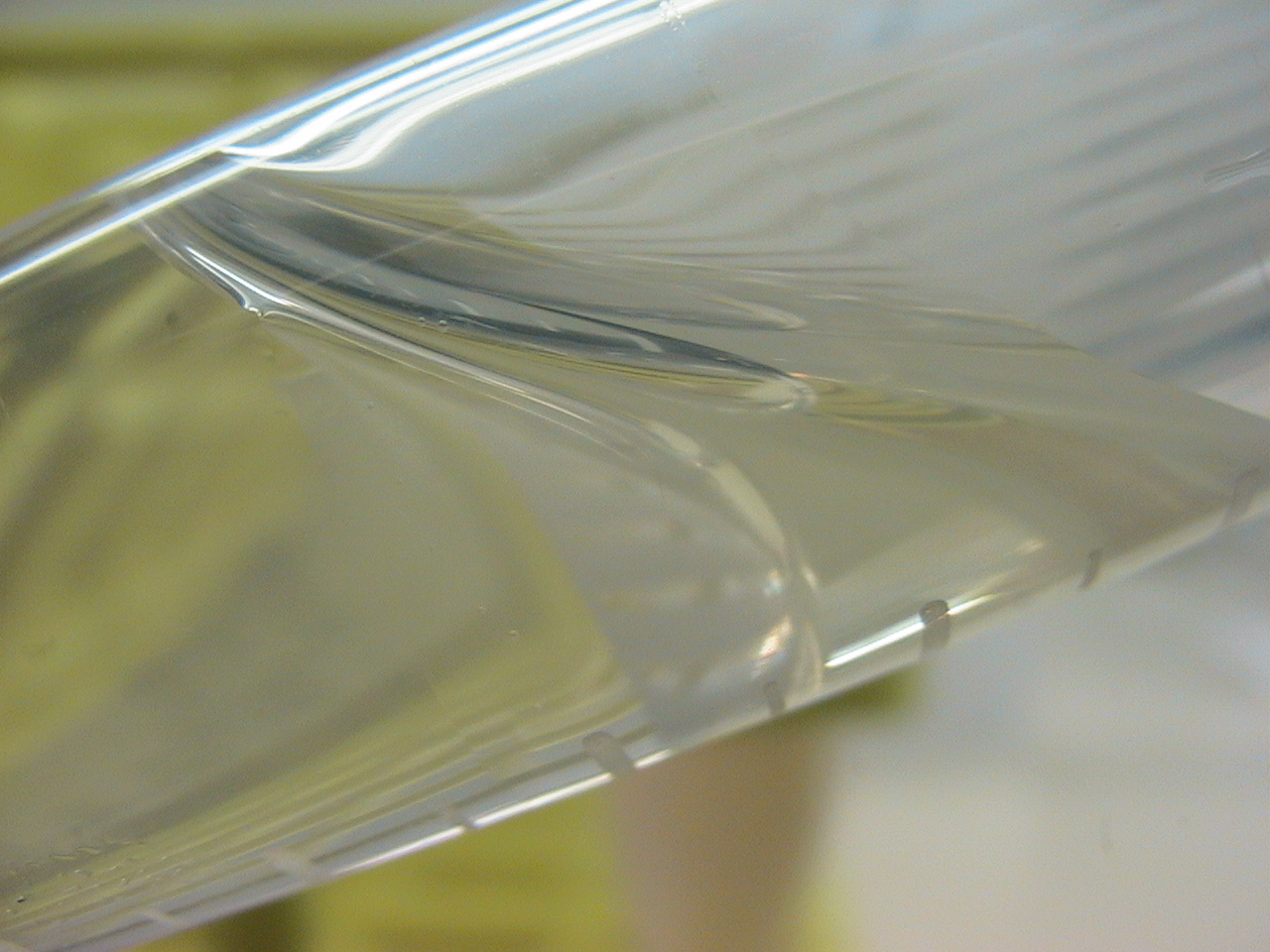

Also, when monomeric, chaplins show to reduce surface tension of water which is illustrated in the figure below. It is clearly visable in the second tube from the right that monomeric chaplins flatten the meniscus at the water-oil interface. However, once assembled into polymeres, this property is lost as can be seen in the second tube from the left, which shows the same features as the tube on the far left which only contains water and oil. The tube on the far right only contained water, oil and Congo Red staining.

Moreover, chaplins are extremely stable, both thermally and chemically. As an illustration, to purify them one has to turn to severe techniques like boiling in SDS and extraction with trifluoroacetic acid. Also, along the entire duration of our project – more than half a year – we did not observe any decline in the physical properties of our purified chaplins, being able to re-use the proteins over and over again.

Chaplins in our project

Overall these small proteins appear to have great potential in all kinds of applicational fields, making them very interesting additions to the parts registry as biobricks. However it was their most remarkable property – their hydrophobicity – which drew our attention to them to use them in our project.

We chose not to make all chaplins into biobricks, but to focus on chaplin C, E and H. Chaplin C is anchored in the cell wall and together with chaplins E and H coat the outside of the cell with a hydrophobic layer. Before ordering our biobricks we codon optimalized them for B. subtilis. Since these proteins are not native to B. subtilis and we were unsure whether it would not degrade them with proteases we tested chaplin degradation in spent medium of B. subtilis. Degradation appeared not to occur.

Also, we did not know whether B. subtilis would successfully secrete the C chaplin and insert it into its cell wall. So in addition to chaplins [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305001 C], [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305003 E] and [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305004 H] we also designed an [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305002 altered C chaplin] which has an added sortase binding motive and included a [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K305005 sortase] BioBrick to our project. Sortase - originating from Staphylococcus aureus - is a well studied protein which anchors surface proteins to the cell wal (Mazmanian et al 1999).

References

Claessen, D; Rink, R; de Jong, W et al. 2003. A novel class of secreted hydrophobic proteins is involved in aerial hyphae formation in Streptomyces coelicolor by forming amyloid-like fibrils. Genes Dev 17 1714-1726

Elliot, MA; Karoonuthaisiri, N; Huang, JQ; et al. 2003 The chaplins: a family of hydrophobic cell-surface proteins involved in aerial mycelium formation in Streptomyces coelicolor. Genes Dev 17 1727-1740

Mazmanian, SK; Liu, G; Ton-That, H; Schneewind, O 1999. Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. Science 285 760-763

Nimittrakoolchai, O; Supothina, S 2007. Deposition of organic-based superhydrophobic films for anti-adhesion and self-cleaning applications. Journal of the European Ceramic Society 28 947-952

"

"