Team:WashU/Splicing

From 2010.igem.org

(→Splicing) |

(→Works Cited) |

||

| (One intermediate revision not shown) | |||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

*Established analytical methods to measure splicing activity using fluorescence spectroscopy and the ImageJ image analysis program (ImageJ Software) | *Established analytical methods to measure splicing activity using fluorescence spectroscopy and the ImageJ image analysis program (ImageJ Software) | ||

*Control pictures of CFP and YFP expressing yeast were taken | *Control pictures of CFP and YFP expressing yeast were taken | ||

| + | <center> | ||

{| | {| | ||

|[[Image:WashU_CFP_ Fluorescence.jpg|thumb|300px|Control CFP/YFP expressing yeast when viewed through the CFP Channel]] | |[[Image:WashU_CFP_ Fluorescence.jpg|thumb|300px|Control CFP/YFP expressing yeast when viewed through the CFP Channel]] | ||

|[[Image:WashU_YFP_ Fluorescence.jpg|thumb|300px|Control CFP/YFP expressing yeast when viewed through the YFP Channel]] | |[[Image:WashU_YFP_ Fluorescence.jpg|thumb|300px|Control CFP/YFP expressing yeast when viewed through the YFP Channel]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | </center> | ||

Detailed information on our experimentation can be found in the teams [https://2010.igem.org/Team:WashU/Notebook laboratory notebook]. | Detailed information on our experimentation can be found in the teams [https://2010.igem.org/Team:WashU/Notebook laboratory notebook]. | ||

==Works Cited== | ==Works Cited== | ||

<font size=1> | <font size=1> | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

*Ast 2004, How did alternative splicing evolve?, Nature reviews. Genetics, v. 5, 773-782 | *Ast 2004, How did alternative splicing evolve?, Nature reviews. Genetics, v. 5, 773-782 | ||

| - | |||

*Bell et. al. 1988, Sex-lethal, A Drosophila Sex Determination Switch Gene, Exhibits Sex-Specific RNA Splicing and Sequence Similarity to RNA Binding Proteins, Cell, v. 55, 1037-1046. | *Bell et. al. 1988, Sex-lethal, A Drosophila Sex Determination Switch Gene, Exhibits Sex-Specific RNA Splicing and Sequence Similarity to RNA Binding Proteins, Cell, v. 55, 1037-1046. | ||

| + | *D. Black. Splicing in the Inner Ear: a Familiar Tune, but What Are the Instruments? Neuron. 1998 v. 20, 165–168. | ||

| + | *ImageJ software 1997-2010. U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/. | ||

| + | *J. Izquierdo, et al. Regulation of Fas Alternative Splicing by Antagonistic Effects of TIA-1 and PTB on Exon Definition. Molecular Cell. 2005 v. 19, 475–484. | ||

| + | *Juneau et. al. 2009, Alternative splicing of PTC7 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae determines protein localization, Genetics, v.183, 185-195 | ||

*Kelley et. al. 1995, Expression of Msl-2 Causes Assembly of Dosage Compensation Regulators on the X Chromosomes and Female Lethality in Drosophila, Cell,, v. 81, 867-877 | *Kelley et. al. 1995, Expression of Msl-2 Causes Assembly of Dosage Compensation Regulators on the X Chromosomes and Female Lethality in Drosophila, Cell,, v. 81, 867-877 | ||

| + | *Klinz, Gallwitz, 1985. Size and position of intervening sequences are critical for the splicing efficiency of pre-mRNA in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic acids research, v.13, 3791-3804 | ||

| + | *Lopez et. al. 1999, Genomic-scale quantitative analysis of yeast pre-mRNA splicing: implications for splice-site recognition, RNA, v. 5, 1135-1137 | ||

*Merendino et. al.1999, Inhibition of msl-2 splicing by Sex lethal reveals interaction between U2AF35 and the 39 splice site AG, Letters to Nature, v.202 p.838-841 | *Merendino et. al.1999, Inhibition of msl-2 splicing by Sex lethal reveals interaction between U2AF35 and the 39 splice site AG, Letters to Nature, v.202 p.838-841 | ||

| + | *Shen, Green, 2006, RS domains contact splicing signals and promote splicing by a common mechanism in yeast through humans, Genes and Development, v. 20, 1755-1765 | ||

*Zamore et. al. 1989, Identification, purification, and biochemical characterization of U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein auxiliary factor,Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA, v. 86, 9243-9246 | *Zamore et. al. 1989, Identification, purification, and biochemical characterization of U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein auxiliary factor,Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA, v. 86, 9243-9246 | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

Latest revision as of 06:41, 27 October 2010

Splicing: The New Alternative

The 2010 Washington University iGEM team is designing a synthetic alternative splicing system in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in order to create a new tool synthetic biologists can use in their scientific endeavors. A single definitive locus and only one other potential locus within the S. cerevisiae genome have shown alternative splicing capabilities (Juneau, 2009). This lack of complex splicing activity within S. cerevisiae limits how synthetic biologists utilize splicing in their projects. The 2010 WashU iGEM team strives to overcome this issue by expressing Sex-Lethal (SxL), a Drosophila Melanogaster splicing regulatory gene, in S. cerevisiae and attempting to use it to control alternative splicing events.

The designed construct employs two 3’ splice sites to select for cyan or yellow fluorescent proteins. By altering the presence of SxL within the cell, the preference between the proximal and distal 3' splice sites can be modulated. This results in varying ratios of CFP and YFP, allowing us to show the creation of a synthetically designed alternative splicing mechanism in S. cerevisiae.

The alternative splicing machine can be applied to isoform engineering, showing the unique benefits of this mechanism. A more complex construct is designed in which the 5' end of a flourscent protein is always included in mRNA. However, different 3' ends are alternatively spliced on, creating different isoforms of a protein. This construct simplistically mirrors the much more complex examples of alternative splicing in nature, as in the avian cochlea. Avian cochlear cells alternatively splice as many as 576 different isoforms of the same gene, helping to create a gradient that is necessary to hear a wide spectrum of sound (Black, 1998). Another possible advantage to alternative splicing is that it allows a combinatorial approach to problem solving, like the one used by the 2006 Davidson iGEM team. Instead of using recombinases to modify DNA, splicing, which only affects RNA transcripts, can be used to leave no lasting change in the cell’s genetic code.

Background

Splicing

Alternative splicing occurs naturally in most eukaryotes as a way to produce many different variations. Two notable examples are the avian cochlear cells and the human Fas receptor protein involved in regulating cell death.

In the inner ear of baby chicks, hair cells are lined along the length of the basilar papilla, a structure within the cochlea. These hair cells are tuned to respond most strongly to a certain frequency of sound, with the ones at the apical end responding to low frequency sounds and those at the basal end responding to high frequency sounds. One element in tuning these hair cells is the oscillation of the membrane potential during cell stimulation, which occurs at the same frequency as the frequency that the cell most strongly responds to. The mechanical stimulation of these cells results in an influx of calcium into the cell, which triggers the calcium-activated potassium channels to open. The influx of calcium followed by the outflux of potassium causes the oscillation in membrane potential. The timing of the calcium-activated potassium channels determine the rate at which the cell can repolarize and subsequently the frequency of oscillation. These calcium-activated channels are encoded by the chicken homolog of the Drosophila Slowpoke gene, which are alternatively spliced to produce many different variants. Each variant result in a different sensitivity of the protein to calcium, hence the variations in membrane potential oscillation frequencies (Black).

The same phenomenon occurs with the Fas gene in humans. The Fas gene encodes for either a membrane bound receptor or a soluble isoform that prevents programmed cell death. When a Fas ligand binds onto a Fas receptor on the cell, it mediates apoptosis or programmed cell death. One of the mechanisms that regulate whether the transmembrane or the insoluble form results is alternative splicing the Fas pre-mRNA. Fas mRNA transcripts with exon 6 spliced out result in the soluble form of the receptor and those including exon 6 result in the membrane bound receptor. Recent studies show that multiple splicing factors are involved in alternatively splicing this transcript (Izquierdo).

Alternative Splicing

One of the more interesting aspects of splicing is a process called alternative splicing. In alternative splicing, a single RNA transcript can be spliced in alternative ways depending on the cellular environment, resulting in different mRNAs that can form different isoforms of the same protein. Thus, a single gene may code for a multitude of proteins.

There are several modes of alternative splicing. This project involves what is called Mutually Exclusive exons because the intron contains a stop codon. If the stop codon containing intron is expressed translation will cease before the second exon, preventing translation of sequences downstream of intron.

Splicing Machinery

Splicing is mediated by a large complex within the nucleus called the spliceosome. The spliceosome is composed of many different proteins and five uradine rich snRNPs (small nuclear ribonucleic proteins). Spliceosome formation is directed by several highly conserved sequences on the pre-mRNA. The three major recognition sequences in S. cerevisiae are highly conserved and are the 5' splice site (N/GTATGT), the 3' splice site (TAG/N), and the branchpoint sequence (TACTAAC), where '/' represents an exon-intron boundary and the 'A' represents the catalytic adenosine at the branchpoint.

Spliceosome Mechanism

To accomplish splicing the spliceosome performs two precise, sequential transesterification reactions which cause the excision of the intron and joining of the two flanking exons. The first reaction involves the nucleophilic attack of the active adenosine of the branch point on the phosphodiester bond of the 5' splice site. This leads to cleavage of the 5' splice site and formation of a lariate intermediate. The 3' OH of the of the 5' exon is then free to attack the 3' splice site. This causes the two exons to join and the intron to be released.

Splicing in S. cerevisiae

S. cerevisiae was chosen as a model organism due to its widespread use in synthetic biology and its low amount of native splicing activity. The lack of abundant alternative splicing mechanisms in S. cerevisiae has prohibited the use of splicing as a synthetic biology tool. Additionally the small amount of naturally occurring splicing activity helps to minimize interference with our synthetic mechanism.

When compared to other Eukaryotes splicing in S. cerevisiae is greatly diminished. Genome wide analysis has shown only 3.8% of S. cerevisiae genes contain introns (Lopez et. al., 1999) and only one example of alternative splicing has been shown (Juneau et. al., 2009). This differs noticably from humans where the average gene contains 7.8 introns and 35-65% of genes are alternatively spliced (Ast, 2004).

Despite the greatly reduced splicing activity in S. cerevisiae it still contains splicing machinery greatly conserved all the way to human systems (Shen et. al., 2006). The high conservation of splicing machinery is what allows the use of a Drosophila regulatory protein, SxL, to be used in S. cerevisiae. Furthermore it makes the designed system highly portable from one organism to the next allowing for widespread application.

Sex-Lethal

Sex Lethal (Sxl) is a gene that is important both for sexual differentiation and dosage compensation in Drosophila melanogaster. As an mRNA binding protein, one of its functions is regulation of mRNA splicing events. (Bell et. al., 1988, Kelley et. al. 1995) The Sxl product can prevent splicing by the splicosome at either the 3’ or 5’ splice sites. This is through competitive binding with U2 Auxiliary Factor (U2AF) to the poly(Y) track within the intron. Normally the U2AF splicing factor binds to the poly(y) tract and recruits the U2 snRNP, a necessary step in spliceosome formation. Having a similar active binding site to U2AF allows Sxl to bind to the same recognition site and block U2AF activity. (Merendino et. al., 1999) When this occurs, two things can happen. The first, as seen in the msl-2 gene of D. melanogaster, is that Sxl binding prevents the excision of an intron. When translated, the intron will code for a premature stop codon and result in a truncated protein. (Merendino et. al., 1999) Another outcome of Sxl binding can be seen in the tra-1 gene of D. melanogaster, where suppressed splicing at one site causes the splicosome to prefer a secondary downstream splice site. This causes a larger intron to be excised, and a different protein product. (Bell et. al., 1988) In both of these cases, the different gene products function in sex determination. Furthermore Sxl is an autoregulatory gene, affecting its own pre-mRNA so that only female cells will express the active protein. (Bell et. al., 1988) In the two examples given, default splicing will result in male, and regulated splicing due to Sxl will result in female phenotype/differentiation.

For our project we have chosen to work with the second type of Sxl regulation, alternative 3' splice site selection. To do this we have included the Sxl binding domain, which is (U)8 or A(U)7, in our construct. (Merendino et. al., 1999) This site is recognized by U2AF in S.s cerevisiae whose binding is required prior to U2 snRNP binding and spliceosome assembly (Zamore et. al., 1989). The expected outcome is that by introducing Sxl and the Sxl binding site to yeast we will be able to regulate native splicing mechanisms to regulate alternative splicing of our construct.

Project Goals

The 2010 WashU iGEM team is attempting to create and modulate a synthetic splicing mechanism in S. cerevisiae. This will add a valuable new tool into the synthetic biologist's tool-belt that can be utilized in many different applications.

Three different genetic constructs are being made and tested by this years iGEM team. Each one builds upon the previous construct in our effort to develop and showcase alternative splicing as a synthetic biology tool.

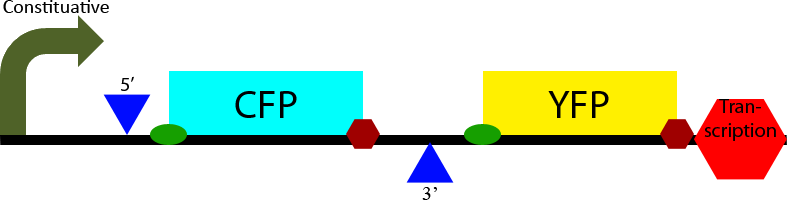

Construct 1

Construct 1 seeks to demonstrate that splicing of the designed intron occurs in S. cerevisiae. To accomplish this it contains two open reading frames, one which codes for CFP and one which codes for YFP. The CFP open reading frame is contained within an intron, causing it to be spliced out. In eukaryotes only the first open reading frame is translated, so in the non-spliced mRNA CFP will be translated and YFP will not be expressed. However in the spliced transcript CFP will be spliced out and YFP will be expressed. Observation of YFP will demonstrate that splicing of the designed intron has occurred within the cell. Observation of CFP will demonstrate that splicing of the designed intron is not 100% effective.

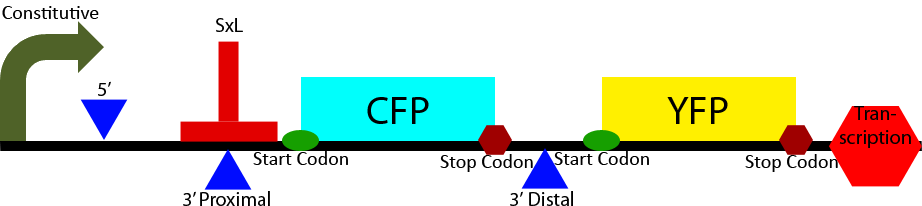

Construct 2

Construct 2 seeks to demonstrate the affect of Sex-Lethal (SxL) expression on 3' splice site selection. It contains a proximal and distal 3' splice sites. The proximal 3' splice site contains a SxL recognition sequence. Initially the proximal 3' splice site is favored due to its greatly decreased intron length (Klinz, Gallwitz, 1985) causing a greater CFP to YFP ratio. Upon expression of SxL the 3' proximal site will be inhibited due to competitive binding between SxL and U2AF (see Project Background section). This will cause a shift in the ratio of CFP to YFP towards YFP demonstrating synthetic controllable alternative splicing within S. cerevisiae.

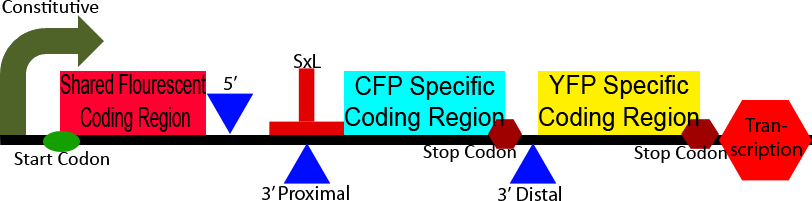

Construct 3

Construct 3 demonstrates an application of our alternative splicing system in order to show the unique advantages that alternative splicing can confer. This construct differs from construct 2 in the CFP and YFP proteins and split between a homologous 5' region and heterologous 3' regions. The 5' homologous region is upstream of the splice sites, causing it to always be include in the processed mRNA, the 3' ends of the two florescent proteins are then alternatively spliced on, leadings to the production of either CFP or YFP. This shows the production of two different isoforms of a fluorescent protein, the ratio of which can be modulated through the use of a splicing regulatory protein.

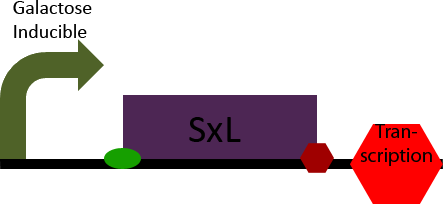

SxL Construct

The SxL construct simply allows inducible expression of the SxL protein in S. cerevisiae. It accomplishes this by placing the D. melanogaster gene SxL under the control of a galactose inducible promoter.

Biobricks

The following biobricks were used in the above constructs:

- The Constitutive Yeast ADH1 Promoter. [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_J63005 BBa_J63005]

- The Inducible Yeast Gal1 Promoter. [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_J63006 BBa_J63006]

- The Designed Yeast Kozak Sequence. [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_J63003 Part:BBa_J63003]

- Engineered Cyan Fluorescent Protein derived from A. victoria GFP. [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_E0020 BBa_E0020]

- Enhanced Yellow Fluorescent Protein derived from A. victoria GFP. [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_E0030 BBa_E0030]

- The Yeast ADH1 Terminator. [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_J63002 BBa_J63002]

Results

- The constructs were made by a mixture of gene synthesis, overlapping PCR and enzyme digests followed by ligation

- The constructs were confirmed by running construct digests on a gel to check for size

- The constructs were linearized and several attempts to transform them into yeast were made.

- Several unsuccessful yeast transformations were attempted, however time did not allow for thorough troubleshooting and successful completion of the process

- Established analytical methods to measure splicing activity using fluorescence spectroscopy and the ImageJ image analysis program (ImageJ Software)

- Control pictures of CFP and YFP expressing yeast were taken

Detailed information on our experimentation can be found in the teams laboratory notebook.

Works Cited

- Ast 2004, How did alternative splicing evolve?, Nature reviews. Genetics, v. 5, 773-782

- Bell et. al. 1988, Sex-lethal, A Drosophila Sex Determination Switch Gene, Exhibits Sex-Specific RNA Splicing and Sequence Similarity to RNA Binding Proteins, Cell, v. 55, 1037-1046.

- D. Black. Splicing in the Inner Ear: a Familiar Tune, but What Are the Instruments? Neuron. 1998 v. 20, 165–168.

- ImageJ software 1997-2010. U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/.

- J. Izquierdo, et al. Regulation of Fas Alternative Splicing by Antagonistic Effects of TIA-1 and PTB on Exon Definition. Molecular Cell. 2005 v. 19, 475–484.

- Juneau et. al. 2009, Alternative splicing of PTC7 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae determines protein localization, Genetics, v.183, 185-195

- Kelley et. al. 1995, Expression of Msl-2 Causes Assembly of Dosage Compensation Regulators on the X Chromosomes and Female Lethality in Drosophila, Cell,, v. 81, 867-877

- Klinz, Gallwitz, 1985. Size and position of intervening sequences are critical for the splicing efficiency of pre-mRNA in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic acids research, v.13, 3791-3804

- Lopez et. al. 1999, Genomic-scale quantitative analysis of yeast pre-mRNA splicing: implications for splice-site recognition, RNA, v. 5, 1135-1137

- Merendino et. al.1999, Inhibition of msl-2 splicing by Sex lethal reveals interaction between U2AF35 and the 39 splice site AG, Letters to Nature, v.202 p.838-841

- Shen, Green, 2006, RS domains contact splicing signals and promote splicing by a common mechanism in yeast through humans, Genes and Development, v. 20, 1755-1765

- Zamore et. al. 1989, Identification, purification, and biochemical characterization of U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein auxiliary factor,Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA, v. 86, 9243-9246

"

"