Team:Berkeley/Project/Payload

From 2010.igem.org

| (One intermediate revision not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| - | In our Payload Delivery assay, we used green fluorescent protein (GFP) as our protein payload because it's delivery can be easily detected through use of fluorescent microscopy. To fill bacteria with our GFP payload, we transformed them with a plasmid containing our construct | + | In our Payload Delivery assay, we used green fluorescent protein (GFP) as our protein payload because it's delivery can be easily detected through use of fluorescent microscopy. To fill bacteria with our GFP payload, we transformed them with a plasmid containing our construct jtk2801, which is [https://2008.igem.org/Team:Cambridge/Improved_GFP ffGFP] driven by a constitutive promoter. Then we turned them into delivery machines by transforming them again with our payload delivery device, fed these bacteria to Choanos, and induced lysis. |

To see the results of this assay, visit our [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Berkeley/Results results page]. | To see the results of this assay, visit our [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Berkeley/Results results page]. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

| + | In order to further confirm delivery, we experimented with delivering a GFP fused to a localization tag along with normal, untagged RFP. One of the first tags we tried was Lifeact, which localizes protein to actin. Unfortunately, this proved toxic to our ''E. coli'', and which did not grow well and formed large filaments that could not be consumed by the choanoflagellates. | ||

| - | + | We also delivered bacteria with regular RFP and a GFP tagged with a nuclear localization signal (NLS). We hoped to observe Choanoflagellates that had a fluorescent red cytoplasm and had glowing green nuclei. This would provide strong evidence of successful delivery, as well as allowing us to later target DNA manipulating proteins like transposons. However, when we delivered bacteria with RFP and NLS+GFP, we saw red and green throughout, meaning the NLS we used (SV40 NLS) was not functional in Choanoflagellates. | |

| - | + | Our future plans include trying other nuclear localization tags that have proven successful in other eukaryotes as well as constructing our own based off of BLASTs of the Choanoflagellate's genome for NLS-like sequences. | |

| - | Our future plans include trying other nuclear localization tags that have proven successful in other eukaryotes as well as constructing our own based off of BLASTs of the Choanoflagellate's genome for NLS-like sequences. | + | |

| - | + | ||

Latest revision as of 23:00, 27 October 2010

- Home

- Project

- Parts

- Self-Lysis

- Vesicle-Buster

- Payload

- [http://partsregistry.org/cgi/partsdb/pgroup.cgi?pgroup=iGEM2010&group=Berkeley Parts Submitted]

- Results

- Judging

- Clotho

- Human Practices

- Team Resources

- Who We Are

- Notebooks:

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Daniela Daniela's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Christoph Christoph's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Amy Amy's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Tahoura Tahoura's Notebook]

- [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Berk2010-Conor Conor's Notebook]

Overview

"Payload" refers to the contents of a bacteria that are desired to be delivered to the cytoplasm of the Choanoflagellate. Payload can come in many forms: proteins, DNA, etc.

Green Fluorescent Protein Payload

In our Payload Delivery assay, we used green fluorescent protein (GFP) as our protein payload because it's delivery can be easily detected through use of fluorescent microscopy. To fill bacteria with our GFP payload, we transformed them with a plasmid containing our construct jtk2801, which is ffGFP driven by a constitutive promoter. Then we turned them into delivery machines by transforming them again with our payload delivery device, fed these bacteria to Choanos, and induced lysis.

To see the results of this assay, visit our results page.

Targeted Fluorescent Protein Payload

In order to further confirm delivery, we experimented with delivering a GFP fused to a localization tag along with normal, untagged RFP. One of the first tags we tried was Lifeact, which localizes protein to actin. Unfortunately, this proved toxic to our E. coli, and which did not grow well and formed large filaments that could not be consumed by the choanoflagellates.

We also delivered bacteria with regular RFP and a GFP tagged with a nuclear localization signal (NLS). We hoped to observe Choanoflagellates that had a fluorescent red cytoplasm and had glowing green nuclei. This would provide strong evidence of successful delivery, as well as allowing us to later target DNA manipulating proteins like transposons. However, when we delivered bacteria with RFP and NLS+GFP, we saw red and green throughout, meaning the NLS we used (SV40 NLS) was not functional in Choanoflagellates. Our future plans include trying other nuclear localization tags that have proven successful in other eukaryotes as well as constructing our own based off of BLASTs of the Choanoflagellate's genome for NLS-like sequences.

Plasmid Payload

Our delivery scheme also has the potential to deliver DNA. We currently are in the process of testing the delivery of several plasmids to the Choanoflagellates, some made by the King Lab and others by the Anderson lab. Most of the plasmids are pQXIN vectors with both SV40 and colE1 origins, and have eGFP under an animal promoter, such as Atub, Ef1a, and Myo. If the plasmids can be successfully delivered, replicated and expressed in the Choanoflagellates, they should glow green, allowing us to detect successful hits by using Flow Cytometry. This wasn't the case with our GFP delivery scheme, because there would be no way to distinguish Choanos that just ate fluorescent bacteria from successful delivery events. However, flow cytometry can be employed for Plasmid Payload, because the bacteria don't express the GFP on the plasmid they're delivering.

Transposase Payload

We're excited to take this project to the next level by delivering proteins that could make Choanoflagellates genetically tractable. Over the summer, we constructed a large portfolio of transposase parts and constructs. Transposases are enzymes capable of randomly cutting out pieces of DNA flanked by short terminal repeat sequences specific to that transposase and pasting them randomly into another stretch of DNA.

Our constructs contain the following three transposases:

- Tn5

- Sleeping Beauty

- PiggyBac

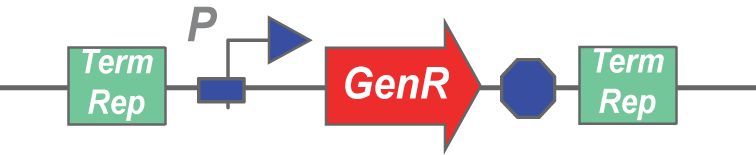

Here's an example transposon:

A transposase would cut this stretch of DNA out of a plasmid, and insert it randomly into another stretch of DNA. Any gene can be inserted in between terminal repeats and used as a transposon.

Tn5

Tn5 transposase is native to E. Coli, but the wild-type protein expressed naturally by the cell is very inactive. Our version of Tn5 has been mutated to render it hyperactive. We added a nuclear localization tag to the Tn5 transposase, so that it would be transported to the Choano nucleus and insert its transposon into the Choano's genome.

Sleeping Beauty

Sleeping Beauty is a synthetic transposase that was made through ‘reverse engineering’ a defective copy of an ancestral Tc1/mariner-like transposase originally found in fish. Our version is SB100X, which is 100 times more active that the wildtype version. It contains an internal nuclear localization tag, so we didn't add an additional one.

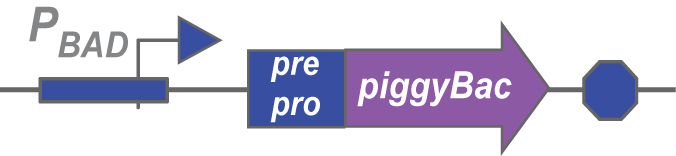

PiggyBac

PiggyBac is transposase originally found in moths. Our version has been codon-optimized to work in mammalian cells.

It contains an internal nuclear localization tag, so we didn't add an additional one.

The importance of Pre-pro

We’ve also prefixed each transposase with a pre-pro, a sequence that targets proteins to the periplasm of the bacteria. This spatial barrier serves two purposes: it prevents the transposase from accesssing its transposon and inserting it into the bacteria’s genome instead of the Choano’s. Such an activity would be detrimental to the bacteria, since the transposon could be inserted into the middle of genes in the bacteria's chromosome, so the pre-pro acts to decrease toxicity of the transposases as well.

Assaying Transposase Function

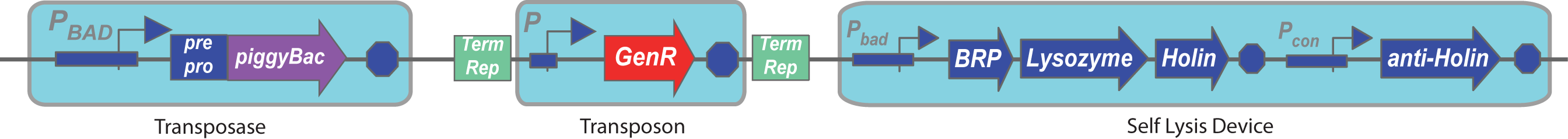

We created the above composite part for all of our transposases, and intend to use them to assay transposase activity.

The assay would involve inducing transposase expression with arabinose, followed by inducing self-lysis with anhydrotetracycline. After the cells have lysed, they should release the transposase from the periplasm and the plasmid containing the GenR transposon from the cytoplasm, allowing the two to mingle in the lysate. If the transposase is functional, it should be able to cut and paste the GenR cassette into an Amp plasmid, which we would add to the lysate in large amounts. The next step involves spinning down the lysate, zymo-ing the supernatant, and transforming bacteria with that zymo'd product. If transposase was functional, it would have created plasmids that confer both Amp and Gen resistance to the bacteria that picked it up during the transformation. Thus, if plating the lysate transformation on Amp+Gen plates leads to colony formation, the transposases are functional.

Note: Co-transformation with the parent plasmid and AmpR plasmid is avoided by using an origin of replication on the GenR plasmid that is not supported by the cells that are transformed with the lysate (GenR plasmid has an R6K origin, and the transformed cells don't express pir).

Zinc Finger Nucleases

In the future, we would also like to deliver Zinc Finger Nucleases that could perform targeted excisions to create Choanoflagellate knockouts.

"

"