Team:UNIPV-Pavia/Project/solution

From 2010.igem.org

m (→PHA production) |

m (→Integrative standard vector for E. coli) |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Several solutions were explored in this project to potentially improve the industrial production of recombinant proteins. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Self-inducible promoters were considered to avoid the usage of inducible systems especially in large-scale industrial bioprocesses, in which protein production has to be triggered by expensive inducer molecules. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Standard and user friendly integrative vectors for E. coli and S. cerevisiae were designed to stably integrate the expression systems of interest in the microbial host genome and to eliminate the need of expensive selection techniques, such as antibiotics or auxotrophic media. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, an "in-cell" protein purification system was implemented using BioBrick parts: PolyHydroxyAlkanoate (PHA) granules were used as a substrate for PHA-binding peptides (Phasins) fused to the target protein, while a pH-based self-cleaving peptide (Intein) was used instead of a protease cleavage site. This solution can thus replace the usage of expensive affinity resins/columns and proteases. | ||

| + | |||

<table align="center" border="0" width="80%"> | <table align="center" border="0" width="80%"> | ||

| Line 86: | Line 95: | ||

=Self-inducible promoters= | =Self-inducible promoters= | ||

| - | The aim of this section is the realization and characterization of a library of self-inducible promoters. These devices are promoters able to initiate the production of the target protein when the cell culture reaches the desired culture density | + | The aim of this section is the realization and characterization of a library of self-inducible promoters. These devices are promoters able to initiate the production of the target protein when the cell culture reaches the desired culture density. |

===<b>Exploiting quorum sensing mechanism...</b>=== | ===<b>Exploiting quorum sensing mechanism...</b>=== | ||

| Line 94: | Line 103: | ||

When a cell population expresses luxI, the concentration of HSL is an increasing function of cell culture density and so the induction of the ''lux pR'' promoter occurs only when the cells reach a threshold density. | When a cell population expresses luxI, the concentration of HSL is an increasing function of cell culture density and so the induction of the ''lux pR'' promoter occurs only when the cells reach a threshold density. | ||

| - | Taking inspiration from this natural regulation mechanism, a library of self-inducible devices was built by engineering quorum sensing circuits in ''E. coli''. The critical cell density was modulated by changing the autoinducer molecule synthesis rate. In this way, the library members can initiate the ''lux pR'' gene expression at different cell densities of the host strain. In ''V. fischeri'', the ''lux pR'' regulates a set of genes involved in the bioluminescence of the bacteria, but in synthetic circuits based on this regulatory mechanism users can regulate the expression of the desired genes. | + | Taking inspiration from this natural regulation mechanism, a library of self-inducible devices was built by engineering quorum sensing circuits in ''E. coli''. The critical cell density was modulated by changing the autoinducer molecule synthesis rate. In this way, the library members can initiate the ''lux pR'' gene expression at different cell densities of the host strain. In ''V. fischeri'', the ''lux pR'' regulates a set of genes involved in the bioluminescence of the bacteria, but in synthetic circuits based on this regulatory mechanism users can regulate the expression of the desired genes (Fig.1). |

| - | [[Image:pv_SenderReceiverAntenna.png|450px|thumb|center|Figure 1 | + | [[Image:pv_SenderReceiverAntenna.png|450px|thumb|center|Figure 1: Sender/receiver behaviour exploited to obtain self-inducible devices]] |

===<b>Parts and system overview</b>=== | ===<b>Parts and system overview</b>=== | ||

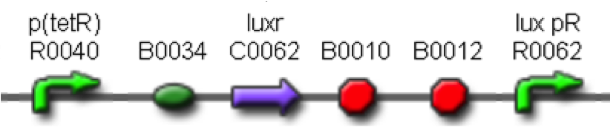

| - | Two BioBrick parts already present in the Registry were used in this module. The RBS-luxI part (<partinfo>BBa_K081008</partinfo>) was assembled upstream of the double terminator <partinfo>BBa_B0015</partinfo>, thus obtaining the fundamental part to build self-inducible circuits, <partinfo>BBa_K300009</partinfo> (Fig. 2). | + | Two BioBrick parts already present in the Registry were used in this module. The RBS-luxI part (<partinfo>BBa_K081008</partinfo>) was assembled upstream of the double terminator <partinfo>BBa_B0015</partinfo>, thus obtaining the fundamental part to build self-inducible circuits, <partinfo>BBa_K300009</partinfo> (Fig.2). |

| - | [[Image:pv_K300009.png|230px|thumb|center|Figure 2 | + | [[Image:pv_K300009.png|230px|thumb|center|Figure 2: <partinfo>BBa_K300009</partinfo> PoPS->HSL sender device.]] |

| - | This part was used as signal generator, while the signal receiver part is <partinfo>BBa_F2620</partinfo> and is shown in Fig. 3. | + | This part was used as signal generator, while the signal receiver part is <partinfo>BBa_F2620</partinfo> and is shown in Fig.3. |

| - | [[Image:pv_F2620.png|350px|thumb|center|Figure 3 | + | [[Image:pv_F2620.png|350px|thumb|center|Figure 3: <partinfo>BBa_F2620</partinfo> receiver device.]] |

| - | In order to build a library of self-inducible devices, another foundamental device was obtained by assembling <partinfo>BBa_K300009</partinfo> upstream of <partinfo>BBa_F2620</partinfo>, thus obtaining the part <partinfo>BBa_K300010</partinfo> (Fig. 4). | + | In order to build a library of self-inducible devices, another foundamental device was obtained by assembling <partinfo>BBa_K300009</partinfo> upstream of <partinfo>BBa_F2620</partinfo>, thus obtaining the part <partinfo>BBa_K300010</partinfo> (Fig.4). |

| - | [[Image:pv_K300010.png|450px|thumb|center|Figure 4 | + | [[Image:pv_K300010.png|450px|thumb|center|Figure 4: <partinfo>BBa_K300010</partinfo>, a PoPS-based self-inducible device.]] |

| - | These systems have the behaviour shown in Fig. 5: luxR is constitutively produced under the control of the tetR promoter, while luxI is produced under the control of a different constitutive promoter. | + | These systems have the behaviour shown in Fig.5: luxR is constitutively produced under the control of the tetR promoter, while luxI is produced under the control of a different constitutive promoter. |

The HSL synthesis rate was modulated by assembling constitutive promoters of different strength upstream of luxI gene. In this way, the ''lux pR'' can be activated when the HSL concentration in the growth media is greater than a threshold, which changes as a function of the HSL synthesis rate. The constitutive promoters were chosen from the ''Anderson Promoters Collection'', available in the Registry. | The HSL synthesis rate was modulated by assembling constitutive promoters of different strength upstream of luxI gene. In this way, the ''lux pR'' can be activated when the HSL concentration in the growth media is greater than a threshold, which changes as a function of the HSL synthesis rate. The constitutive promoters were chosen from the ''Anderson Promoters Collection'', available in the Registry. | ||

| - | [[Image:pv_I80_working.png|450px|thumb|center|Figure 5 | + | [[Image:pv_I80_working.png|450px|thumb|center|Figure 5: Self-inducible devices behaviour. ''Pcon'' is a generic constitutive promoter.]] |

| - | Besides the use of constitutive promoters of different strength to regulate the production of the signal molecule, the plasmid copy number was taken into consideration as another important parameter. The studied combinations are summarized in Fig. 6, 7 and 8. | + | Besides the use of constitutive promoters of different strength to regulate the production of the signal molecule, the plasmid copy number was taken into consideration as another important parameter. The studied combinations are summarized in Fig.6, 7 and 8. |

{| align='center' | {| align='center' | ||

| - | |[[Image:pv_HCHC.png|330px|thumb|center|Figure 6 | + | |[[Image:pv_HCHC.png|330px|thumb|center|Figure 6: Both sender and receiver are assembled on high copy number plasmid. ]]||[[Image:pv_LCLC.png|330px|thumb|center|Figure 7: Both sender and receiver are assembled on low copy number plasmid.]] |

|} | |} | ||

{| align='center' | {| align='center' | ||

| - | |[[Image:pv_HCLC.png|330px|thumb|center|Figure 8 | + | |[[Image:pv_HCLC.png|330px|thumb|center|Figure 8: Sender part in low copy number plasmid and receiver on high copy number plasmid.]] |

|} | |} | ||

Thus, these BioBrick parts can be used to express recombinant proteins without adding an inducer to trigger the transcription initiation of downstream genes; in large-scale production of such proteins this strategy can be cost saving and ease the entire process. Users can rationally choose the cell density at which the initiation has to occur by selecting a self-inducible device library member. | Thus, these BioBrick parts can be used to express recombinant proteins without adding an inducer to trigger the transcription initiation of downstream genes; in large-scale production of such proteins this strategy can be cost saving and ease the entire process. Users can rationally choose the cell density at which the initiation has to occur by selecting a self-inducible device library member. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| align='center' | ||

| + | |[[Image:pv_curva_od_stilizzata.png|500px|thumb|center|Figure 9: behaviour of self-inducible device library members. Each device is able to initiate the synthesis of the recombinant protein of interest at a specific cell density.]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

<div align="right"><small>[[#indice|^top]]</small></div> | <div align="right"><small>[[#indice|^top]]</small></div> | ||

| Line 137: | Line 150: | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

| - | =Integrative standard vector for E. coli= | + | =Integrative standard vector for ''E. coli''= |

The integration of the genetic circuits of interest into the microbial host genome can eliminate the need of expensive selection techniques, such as antibiotics or auxotrophic media, in cell cultures. | The integration of the genetic circuits of interest into the microbial host genome can eliminate the need of expensive selection techniques, such as antibiotics or auxotrophic media, in cell cultures. | ||

| - | In order to simplify the engineering of the host genome, two standard and modular integrative vectors have been designed for Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two commonly used hosts for industrial protein production. Here, a detailed description of the integrative vector for ''E. coli'' is reported, while the following section deals with the integrative vector for yeast. | + | In order to simplify the engineering of the host genome, two standard and modular integrative vectors have been designed for Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two commonly used hosts for industrial protein production. Here, a detailed description of the integrative vector for ''E. coli'' is reported, while the following section deals with the integrative vector for yeast. The parts notation is reported in Fig.11. |

| - | The structure of the designed vector, here named <partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo>, is shown in Fig. | + | The structure of the designed vector, here named <partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo>, is shown in Fig.10. Most of its features have been inspired by <partinfo>BBa_I51020</partinfo> (BioBrick base vector) and <partinfo>BBa_J72007</partinfo> (BamHI methyltransferase encoding CRIM plasmid), described by [Shetty RP et al., 2008] and [Anderson JC et al., 2010] respectively. |

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |valign=top|[[Image:k300000.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure | + | |valign=top|[[Image:k300000.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure 10: BioBrick integrative base vector <partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo>.]] |

| - | |[[Image:glossary300000.jpg|thumb|300px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:glossary300000.jpg|thumb|300px|center|Figure 11: Parts notation.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 198: | Line 211: | ||

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

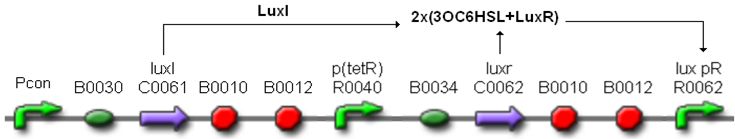

| - | |[[Image:guide.jpg|thumb|800px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:guide.jpg|thumb|800px|center|Figure 12: How to engineer the integrative base vector to assemble the desired DNA ''guide''.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| - | #Be sure to have the desired ''guide'' in the RFC10 standard or a compatible one (Fig. | + | #Be sure to have the desired ''guide'' in the RFC10 standard or a compatible one (Fig.12-a). |

| - | #Digest the ''guide'' with XbaI-SpeI (Fig. | + | #Digest the ''guide'' with XbaI-SpeI (Fig.12-b). |

| - | #Digest the integrative base vector <partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo> with NheI (Fig. | + | #Digest the integrative base vector <partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo> with NheI (Fig.12-c) and dephosphorylate the linearized vector to prevent re-ligation. |

| - | #Ligate the digestion products (Fig. | + | #Ligate the digestion products (Fig.12-d). XbaI, SpeI and NheI all have compatible protruding ends. Note that the ligation is not directional, but the ''guide'' can work in both directions. |

#Transform the ligation in a ''ccdB''-tolerant strain and screen the clone. | #Transform the ligation in a ''ccdB''-tolerant strain and screen the clone. | ||

| Line 211: | Line 224: | ||

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |[[Image:passenger.jpg|thumb|800px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:passenger.jpg|thumb|800px|center|Figure 13: How to engineer the integrative base vector to assemble the desired DNA ''passenger''.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| - | #Be sure to have the desired ''passenger'' in the RFC10 standard or a compatible one (Fig. | + | #Be sure to have the desired ''passenger'' in the RFC10 standard or a compatible one (Fig.13-a). |

| - | #Digest the ''passenger'' with EcoRI-PstI (Fig. | + | #Digest the ''passenger'' with EcoRI-PstI (Fig.13-b). |

| - | #Digest the integrative base vector <partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo> with EcoRI-PstI (Fig. | + | #Digest the integrative base vector <partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo> with EcoRI-PstI (Fig.13-c). |

| - | #Ligate the digestion products (Fig. | + | #Ligate the digestion products (Fig.13-d). |

#Transform the ligation in a pir+/pir-116 strain. Transformants with the uncut plasmid contaminant DNA do not grow because of the ''ccdB'' toxin in <partinfo>BBa_I52002</partinfo>. Screen the clone. | #Transform the ligation in a pir+/pir-116 strain. Transformants with the uncut plasmid contaminant DNA do not grow because of the ''ccdB'' toxin in <partinfo>BBa_I52002</partinfo>. Screen the clone. | ||

| Line 239: | Line 252: | ||

This integration method is applicable when the host strain does not have prophages in the att(Phi80) locus. TOP10 (<partinfo>BBa_V1009</partinfo>) and DH5alpha (<partinfo>BBa_V1001</partinfo>) strains have the Phi80 prophage and so their chromosome cannot be engineered with this procedure. | This integration method is applicable when the host strain does not have prophages in the att(Phi80) locus. TOP10 (<partinfo>BBa_V1009</partinfo>) and DH5alpha (<partinfo>BBa_V1001</partinfo>) strains have the Phi80 prophage and so their chromosome cannot be engineered with this procedure. | ||

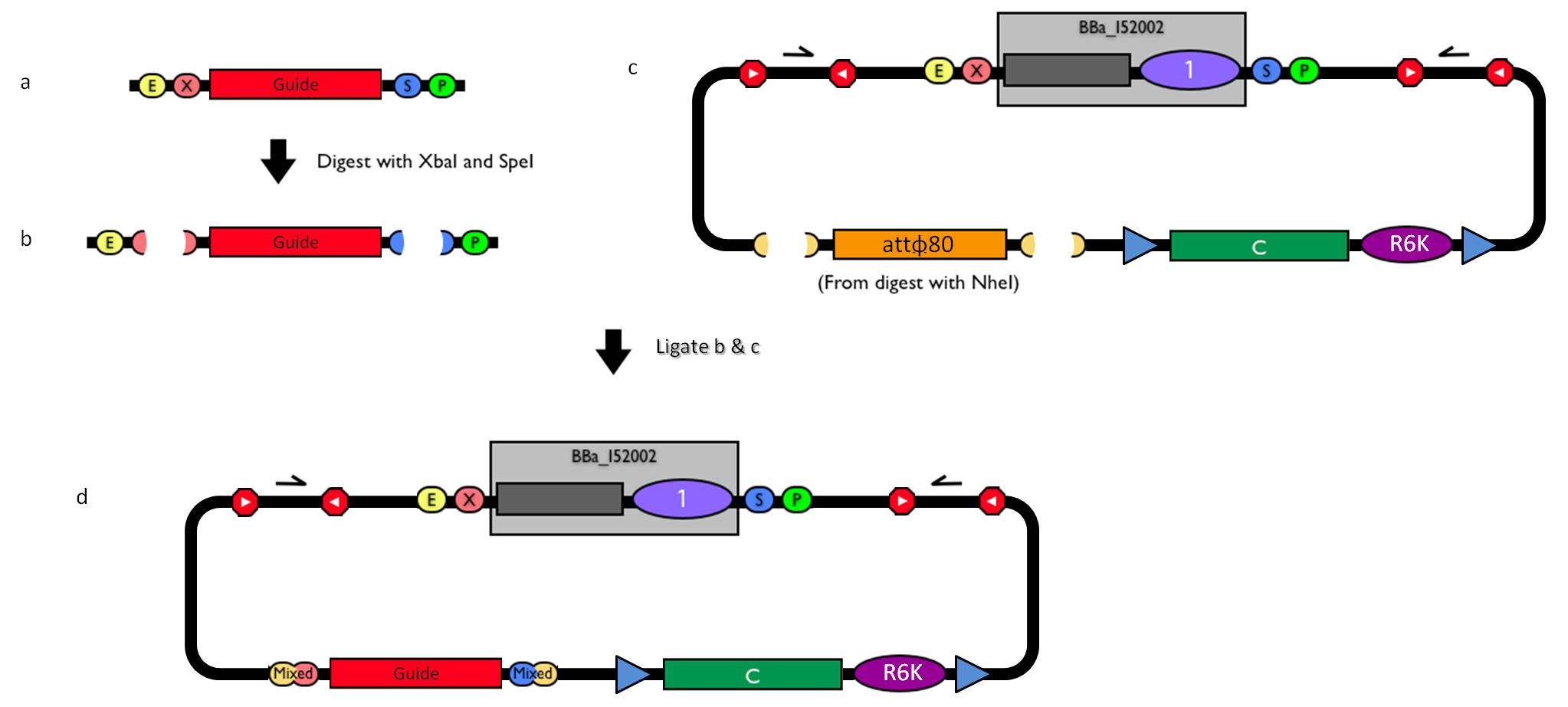

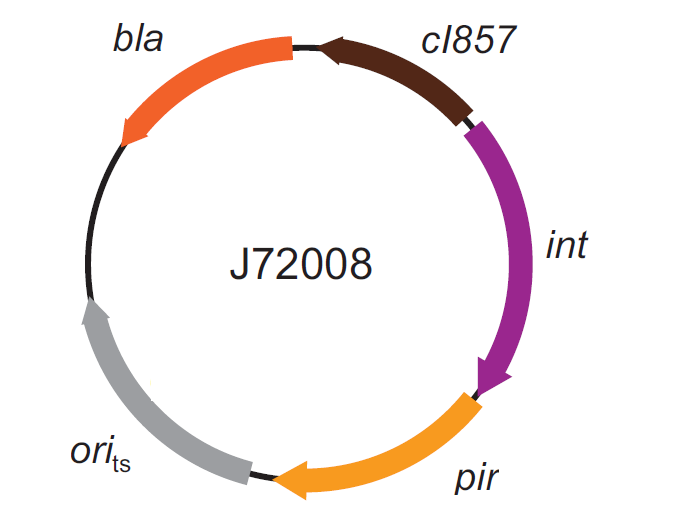

| - | The genomic integration of the desired BioBrick part into the attP(Phi80) locus has to be mediated by co-transforming a helper plasmid, such as the Amp-resistant <partinfo>BBa_J72008</partinfo> plasmid | + | The genomic integration of the desired BioBrick part into the attP(Phi80) locus has to be mediated by co-transforming a helper plasmid, such as the Amp-resistant <partinfo>BBa_J72008</partinfo> plasmid, which carries the IntPhi80 site-specific integrase gene under the control of a thermoinducible promoter (see Fig.14). The helper plasmid also has a heat-sensitive replication origin, whose replication can be inhibited at temperatures of 37-42°C, while a permissive temperature for this vector is 30°C. For this reason, it can be cured at high temperatures, when the integrase expression is triggered at the same time. |

| - | The Phi80 integrase mediates the site-specific recombination between the attP site in the integrative vector and the attB site in the bacterial genome (for a schematic description of this process, see Fig. | + | The Phi80 integrase mediates the site-specific recombination between the attP site in the integrative vector and the attB site in the bacterial genome (for a schematic description of this process, see Fig.15 and http://partsregistry.org/Recombination). |

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |valign=top|[[Image:k300000helper.jpg|thumb|330px|center|Figure | + | |valign=top|[[Image:k300000helper.jpg|thumb|330px|center|Figure 14: Schematic description of the <partinfo>BBa_J72008</partinfo> plasmid. ''cI857'' is the expression system for the thermoinducible cI repressor; ''int'' is the Phi80 integrase regulated by the lambda cI-repressible promoter; ''pir'' is the expression system for the pir-116 gene which is able to trigger the propagation of the R6K conditional replication origin; ''ori_ts'' is the heat-sensitive replication origin (low copy) of the vector; ''bla'' is the Ampicillin resistance marker.]] |

| - | |valign=top|[[Image:k300000recombsite.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure | + | |valign=top|[[Image:k300000recombsite.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure 15: Schematic description of site-specific recombination between a bacteriophage attP attachment site in the plasmid and an attB attachment site in the bacterial genome. In this way the sequence of interest (called "Part" in the figure) can be stably integrated into the attB genomic locus. This process is mediated by a specific integrase.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 252: | Line 265: | ||

===How to perform multiple integrations in the same genome=== | ===How to perform multiple integrations in the same genome=== | ||

| - | When this vector is integrated in the genome, the desired ''passenger'' should be maintained into the host, as well as the Chloramphenicol resistance marker and the R6K conditional replication origin. The CmR and the R6K can be excised from the genome by exploiting the two FRT recombination sites that flank them. The Flp recombinase protein mediates this recombination event (for a schematic description of this process, see Fig. | + | When this vector is integrated in the genome, the desired ''passenger'' should be maintained into the host, as well as the Chloramphenicol resistance marker and the R6K conditional replication origin. The CmR and the R6K can be excised from the genome by exploiting the two FRT recombination sites that flank them. The Flp recombinase protein mediates this recombination event (for a schematic description of this process, see Fig.16 and http://partsregistry.org/Recombination), so it has to be expressed by a helper plasmid, such as pCP20 (CGSC#7629). |

This enables the sequential integration of several parts using the same antibiotic resistance marker, which can be each time eliminated. | This enables the sequential integration of several parts using the same antibiotic resistance marker, which can be each time eliminated. | ||

| Line 264: | Line 277: | ||

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |[[Image:k300000recombfrt.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:k300000recombfrt.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure 16: Schematic description of direct repeat-recombination between two FRT sites which flank the R6K-CmR DNA. In this way, the R6K-CmR DNA is excised from the construct and a single FRT site remains in the molecule. This process is mediated by a specific recombinase, the Flp recombinase, which recognizes the FRT sites.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 278: | Line 291: | ||

Here, a detailed description of the integrative vector for the yeast ''S. cerevisiae'' is reported. | Here, a detailed description of the integrative vector for the yeast ''S. cerevisiae'' is reported. | ||

| - | The structure of the designed vector, here named BBa_K300001, is shown in Fig. | + | The structure of the designed vector, here named <partinfo>BBa_K300001</partinfo>, is shown in Fig.17. Most of its features have been inspired by the pUG6 plasmid (GenBank: AF298793.1), constructed by [Guldener U et al., 1996]. The parts notation is reported in Fig.18. |

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |valign=top|[[Image:k300001base.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure | + | |valign=top|[[Image:k300001base.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure 17: BioBrick integrative base vector <partinfo>BBa_K300001</partinfo>.]] |

| - | |[[Image:glossary300001.jpg|thumb|300px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:glossary300001.jpg|thumb|300px|center|Figure 18: Parts notation.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 328: | Line 341: | ||

===How to integrate a BioBrick into the yeast genome=== | ===How to integrate a BioBrick into the yeast genome=== | ||

| - | #Digest <partinfo>BBa_K300001</partinfo> and the desired BioBrick part with EcoRI-SpeI and ligate them (Fig. | + | #Digest <partinfo>BBa_K300001</partinfo> and the desired BioBrick part with EcoRI-SpeI and ligate them (Fig.19). |

#Propagate the resulting plasmid in ''E. coli'' and extract plasmid DNA from bacteria. | #Propagate the resulting plasmid in ''E. coli'' and extract plasmid DNA from bacteria. | ||

| - | #Digest the resulting plasmid with SbfI to linearize the DNA of interest (Fig. | + | #Digest the resulting plasmid with SbfI to linearize the DNA of interest (Fig.20). This is known to increase the integration efficiency from 10- to 50-fold when compared to a non-linearized DNA [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K300001:Design#References Reference 11]. |

| - | #Transform the linearized plasmid into ''S. cerevisiae'' and select integrants on G418 antibiotic plates (Fig. | + | #Transform the linearized plasmid into ''S. cerevisiae'' and select integrants on G418 antibiotic plates (Fig.21). |

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |[[Image:k300001.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:k300001.jpg|thumb|500px|center|Figure 19: Assembly of the desired BioBrick part into the integrative vector.]] |

|} | |} | ||

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |[[Image:linear300001.jpg|thumb|600px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:linear300001.jpg|thumb|600px|center|Figure 20: The plasmid can be linearized upon SbfI digestion to separate the yeast DNA fragment (containing the part of interest and the LoxP-KanMX-LoxP cassette) from the ''E. coli'' DNA fragment (containing the replication origin and the Amp resistance).]] |

|} | |} | ||

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |[[Image:recomb300001.jpg|thumb|600px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:recomb300001.jpg|thumb|600px|center|Figure 21: Integration of the BioBrick of interest into the ''S. cerevisiae'' genome by homologous recombination. In this figure, the integration in the Gal system genomic region is shown.]] |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 349: | Line 362: | ||

===How to perform the KanMX marker excision=== | ===How to perform the KanMX marker excision=== | ||

| - | The KanMX dominant selection marker is flanked by two loxP recombination sites and for this reason it can be excided upon Cre recombinase activity. The Cre recombinase has to be expressed by a helper plasmid. | + | The KanMX dominant selection marker is flanked by two loxP recombination sites and for this reason it can be excided upon Cre recombinase activity (Fig.22). The Cre recombinase has to be expressed by a helper plasmid. |

{|align=center | {|align=center | ||

| - | |[[Image:loxp300001.jpg|thumb|600px|center|Figure | + | |[[Image:loxp300001.jpg|thumb|600px|center|Figure 22: KanMX excision with loxP sites recombination. For more details about this process, see http://partsregistry.org/Recombination]] |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 364: | Line 377: | ||

=Self-cleaving affinity tags to easily purify proteins= | =Self-cleaving affinity tags to easily purify proteins= | ||

| - | Conventional affinity-based protein purification methods rely on specific binding of the fusion tag to an immobilized ligand, but they are affected by severe limitations. | + | Conventional affinity-based protein purification methods rely on specific binding of the fusion tag to an immobilized ligand, but they are affected by severe limitations, as explained in the Motivation section. Briefly, they imply the use of expensive proteases for tag removal from the fusion protein, requiring the appropriate aminoacidic sequence to be included between the tag and the target protein. Moreover, the cost of the affinity resins used in the process is far from negligible, especially on industrial scale. |

| + | |||

| + | The use of self-cleaving protein elements coupled with innovative affinity tags has been recently proposed to overcome these limitations. For all these reasons, in this section a technique compliant to the BioBrick assembly standard and based on self-splicing affinity tags derived from the fusion of Phasins, Inteins and a short flexible linker is proposed. | ||

==Tag== | ==Tag== | ||

===Phasin=== | ===Phasin=== | ||

| - | Phasins are proteins involved in formation and stabilization of PolyHydroxyAlkanoates (PHA) intracytoplasmic inclusions in microorganisms like ''Ralstonia eutropha'' | + | Phasins are proteins involved in formation and stabilization of PolyHydroxyAlkanoates (PHA), intracytoplasmic inclusions in microorganisms like ''Ralstonia eutropha'' which serve as carbon and energy storage. As such, Phasins exhibit highly specific binding to PHA granules and can be used to create tags for proteins, while PHB can be used as the affinity matrix. |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | In literature, it has also been shown that the Phasin-tagged fusion protein's affinity with PHA granules can be improved by increasing the number of Phasins in the fusion protein. | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | The ''Ralstonia eutropha''‘s Phasin coding sequence, <partinfo>K208001</partinfo>, was already present in the Registry in Silver standard. However, at the end of this gene there was a TGA stop codon which prevents the usage of this Phasin as a head or internal domain. | |

| - | -- | + | In order to overcome this problem, <partinfo>K208001</partinfo> has been improved for fusion protein applications by mutagenesis through PCR using custom primers. Two new BioBrick parts were built and submitted to the Registry: |

| + | |||

| + | * <partinfo>BBa_K300002</partinfo>: Phasin - head domain (removed stop codon; Assembly Standard 10 prefix; Silver Standard suffix) | ||

| + | * <partinfo>BBa_K300003</partinfo>: Phasin - internal domain (removed stop codon; Silver Standard prefix; Silver Standard suffix) | ||

| + | |||

| + | These two new parts allow the construction of composite synthetic affinity tags, built by assembling an arbitrary number of Phasins (it has been shown that a better affinity is achieved by fusing of two or more Phasins). In this work a flexible linker sequence (<partinfo>BBa_K105012</partinfo>) that connects the Phasins has also been used in order to test if it can improve or facilitate the binding and folding of the tag. | ||

===PHA production=== | ===PHA production=== | ||

| - | PHA production in ''R. eutropha'' is achieved by the PhaCAB operon, which contains three genes, phbC, phbA and phbB, each encoding for an enzyme essential for the formation of | + | PHA production in ''R. eutropha'' is achieved by the PhaCAB operon, which contains three genes, phbC, phbA and phbB, each encoding for an enzyme essential for the formation of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB, a kind of polyhydroxyalkanoate) inclusions. In literature, the production of PHB has already been achieved in ''E. coli'' by incorporating the PhaCAB operon. The PHB granules produced by engineered ''E. coli'' can be used as an affinity matrix for Phasin-based affinity tags and the binding of the Phasin-tagged protein of interest can occur ''in vivo''. |

| - | + | ||

| + | Several parts for PHB production are present in the Registry: in the past iGEM editions, the Duke (2008 and 2009), Hawaii (2008), Tsinghua (2008), Virginia (2008) teams worked on it and submitted a set of BioBrick parts for PHB synthesis. However, the complete phaCAB operon is not available in the Registry. Because a lot of work about PHB has already been done and because our short term goal was not to optimize the PHB granules productions, an existing engineered ''E. coli'' strain able to produce PHB was used as a proof-of-concept affinity matrix producer. This strain comes from the DSMZ public collection and is named <html><a href="http://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/plasmid_info.php?dsmz_no=15372" target="_blank">DMSZ15372</a></html>. | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| - | Taking advantage of natural affinity of | + | Taking advantage of the natural affinity of Phasins to PHB, it is possible to engineer strains in which PHB and the Phasin-tagged protein of interest are co-produced and the binding can occur. The overall yield and specificity of the process depends on the structure of the Phasin-based tags, which can be easily constructed or modified by using BioBrick parts compatible with the common RFC10 and RFC23 standards to perform in-frame assemblies. |

| - | [[Image:UNIPV10_generic_tag.jpg|thumb|170px|center|Figure | + | For this reason these tags are modular and can be freely expanded; a generic one is shown in Fig.23. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:UNIPV10_generic_tag.jpg|thumb|170px|center|Figure 23: Generic tag composed by two Phasin coding sequences separated by a flexible peptide linker coding sequence.]] | ||

==Protein purification system== | ==Protein purification system== | ||

| + | Phasins and PHB granules can replace the common affinity tags and matrix respectively. However, expensive proteases are still essential to remove the tag after the Phasins-PHB binding. A novel engineered inducible Intein can be used to complete the purification process by removing the affinity tag, thus replacing proteases. | ||

===Intein=== | ===Intein=== | ||

| - | Inteins (Intervening Proteins) are sequences capable of self-exciding from a | + | Inteins (Intervening Proteins) are sequences capable of self-exciding from a precursor protein through a process known as self-splicing, forming a peptide bond between the flanking proteins (exteins). Many so-called mini-Inteins have been engineered, whose key feature is the capability to completely release a flanking extein (the target protein) in response to a simple stimulus, either chemical or physical, with no need of expensive proteases. |

| + | |||

| + | In literature, one mini-Intein was obtained through mutagenesis of ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' ''Mtu RecA'' Intein. The sequence of this Intein, referred to as ΔI-CM, allows for pH/heat-controlled C-terminal cleavage. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thanks to this feature, the ΔI-CM Intein can be fused downstream of an affinity tag and upstream of the protein coding sequence of interest in order to enable a cheap cleavage process to remove the N-terminal tag. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this project, the ΔI-CM Intein sequence was designed according to [Wood DW et al., 1999] and codon-optimized for ''E. coli'' to yield <partinfo>BBa_K300004</partinfo>. This part was designed as an internal domain (prefix and suffix compatible with Silver standard) in order to enable protein coding sequence assemblies to generate the desired synthetic self-cleavable affinity tags for protein purification. | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| - | Thus, it | + | Thus, it is possible to create an engineered protein purification system that uses the tag construct and relies on Intein self-cleaving capabilities. Fig.24 shows a generic purification tag, composed by Phasins and Intein, as an example. |

| - | [[Image:UNIPV10_generic_purification.jpg|thumb|400px|center|Generic purification system.]] | + | [[Image:UNIPV10_generic_purification.jpg|thumb|400px|center|Figure 24: Generic purification system.]] |

Protein purification takes place as follows: | Protein purification takes place as follows: | ||

| - | :1. Affinity tag (and consequently fused protein) binding to PolyHydroxyAlkanoates. | + | :1. Affinity tag (and consequently fused protein) binding to PolyHydroxyAlkanoates (Fig.25). |

| - | [[Image:UNIPV10_binding_activity.png|thumb|400px|center| | + | [[Image:UNIPV10_binding_activity.png|thumb|400px|center|Figure 25: ''In vivo'' binding activity.]] |

:2. Cells lysis. | :2. Cells lysis. | ||

| - | :3. Intein cleavage through pH | + | :3. Recovery of the fused protein, bound with PHA granules, by centrifugation. |

| - | [[Image:UNIPV10_purification_step.png|thumb|150px|center|Purification.]] | + | :4. Elution in the supernatant of the target protein by Intein cleavage through a pH or heat stimulus (Fig.26). |

| + | [[Image:UNIPV10_purification_step.png|thumb|150px|center|Figure 26: Purification.]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:20, 26 October 2010

|

Several solutions were explored in this project to potentially improve the industrial production of recombinant proteins. Self-inducible promoters were considered to avoid the usage of inducible systems especially in large-scale industrial bioprocesses, in which protein production has to be triggered by expensive inducer molecules. Standard and user friendly integrative vectors for E. coli and S. cerevisiae were designed to stably integrate the expression systems of interest in the microbial host genome and to eliminate the need of expensive selection techniques, such as antibiotics or auxotrophic media. Finally, an "in-cell" protein purification system was implemented using BioBrick parts: PolyHydroxyAlkanoate (PHA) granules were used as a substrate for PHA-binding peptides (Phasins) fused to the target protein, while a pH-based self-cleaving peptide (Intein) was used instead of a protease cleavage site. This solution can thus replace the usage of expensive affinity resins/columns and proteases.

Thus, these BioBrick parts can be used to express recombinant proteins without adding an inducer to trigger the transcription initiation of downstream genes; in large-scale production of such proteins this strategy can be cost saving and ease the entire process. Users can rationally choose the cell density at which the initiation has to occur by selecting a self-inducible device library member.

Integrative standard vector for E. coliThe integration of the genetic circuits of interest into the microbial host genome can eliminate the need of expensive selection techniques, such as antibiotics or auxotrophic media, in cell cultures. In order to simplify the engineering of the host genome, two standard and modular integrative vectors have been designed for Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two commonly used hosts for industrial protein production. Here, a detailed description of the integrative vector for E. coli is reported, while the following section deals with the integrative vector for yeast. The parts notation is reported in Fig.11.

This vector can be considered as a base vector, which can be specialized to target the desired integration site in the host genome. The default version of this backbone has the bacteriophage Phi80 attP (<partinfo>BBa_K300991</partinfo>) as integration site. This vector enables multiple integrations in different positions of the same genome.

GlossaryThe passenger is the desired DNA part to be integrated into the genome. The guide is the DNA sequence that is used to target the passenger into a specific locus in the genome.

Design featuresThe main design features for vector engineering and for the genome integration of the vector are reported below. Vector engineering features:

Genome integration features:

How to use it<partinfo>BBa_K300000</partinfo> can be:

How to propagate it before performing genome integrationThe default version of this vector contains the <partinfo>BBa_I52002</partinfo> insert, so it *must* be propagated in a ccdB-tolerant strain such as DB3.1 (<partinfo>BBa_V1005</partinfo>). After the insertion of the desired BioBrick part in the cloning site, this vector does not contain a standard replication origin anymore, so it *must* be propagated in a pir+ or pir-116 strain such as BW25141 (<partinfo>BBa_K300984</partinfo>) or BW23474 (<partinfo>BBa_K300985</partinfo>) that can replicate the R6K conditional origin (<partinfo>BBa_J61001</partinfo>).

How to engineer itThe DNA guide can be changed as follows:

How to perform genome integrationThe integration into the E. coli chromosome can exploit the bacteriophage attP-mediated integration or the homologous recombination. Detailed protocols about attP-mediated integration can be found here:

Detailed protocols about homologous recombination can be found here:

This integration method is applicable when the host strain does not have prophages in the att(Phi80) locus. TOP10 (<partinfo>BBa_V1009</partinfo>) and DH5alpha (<partinfo>BBa_V1001</partinfo>) strains have the Phi80 prophage and so their chromosome cannot be engineered with this procedure. The genomic integration of the desired BioBrick part into the attP(Phi80) locus has to be mediated by co-transforming a helper plasmid, such as the Amp-resistant <partinfo>BBa_J72008</partinfo> plasmid, which carries the IntPhi80 site-specific integrase gene under the control of a thermoinducible promoter (see Fig.14). The helper plasmid also has a heat-sensitive replication origin, whose replication can be inhibited at temperatures of 37-42°C, while a permissive temperature for this vector is 30°C. For this reason, it can be cured at high temperatures, when the integrase expression is triggered at the same time. The Phi80 integrase mediates the site-specific recombination between the attP site in the integrative vector and the attB site in the bacterial genome (for a schematic description of this process, see Fig.15 and http://partsregistry.org/Recombination). Thanks to its R6K conditional replication origin, the integrative vector cannot be replicated in common E. coli strains, so the Chloramphenicol resistant bacteria are actual integrants. In the Materials and Methods section (https://2010.igem.org/Team:UNIPV-Pavia/Project/results), a detailed protocol to target the desired BioBrick part into the Phi80 locus is reported. How to perform multiple integrations in the same genomeWhen this vector is integrated in the genome, the desired passenger should be maintained into the host, as well as the Chloramphenicol resistance marker and the R6K conditional replication origin. The CmR and the R6K can be excised from the genome by exploiting the two FRT recombination sites that flank them. The Flp recombinase protein mediates this recombination event (for a schematic description of this process, see Fig.16 and http://partsregistry.org/Recombination), so it has to be expressed by a helper plasmid, such as pCP20 (CGSC#7629). This enables the sequential integration of several parts using the same antibiotic resistance marker, which can be each time eliminated.

Detailed protocols about homologous recombination can be found here:

Integrative standard vector for yeastHere, a detailed description of the integrative vector for the yeast S. cerevisiae is reported. The structure of the designed vector, here named <partinfo>BBa_K300001</partinfo>, is shown in Fig.17. Most of its features have been inspired by the pUG6 plasmid (GenBank: AF298793.1), constructed by [Guldener U et al., 1996]. The parts notation is reported in Fig.18. This is an integrative vector which can be used to insert the desired RFC10-compatible BioBrick parts/devices/systems into the genome of S. cerevisiae. This vector can also be specialized to target the desired integration site in the host genome. The default version of this backbone targets the Gal system of the S288C strain (<partinfo>BBa_K300979</partinfo>) through the two homologous regions <partinfo>BBa_K300986</partinfo> and <partinfo>BBa_K300987</partinfo>. The Gal system is not essential for yeast survival if the strain is grown on carbon sources other than galactose. This vector enables multiple integrations in different positions of the same genome. The usage of the KanMX dominant selection marker can avoid the usage of auxotrophic markers. In the industrial framework auxotrophies are usually deleterious for the process productivity because they affect the growth rate of cells. For this reason, this vector can be a concrete solution for the design of industrial yeast strains with novel user-defined functions.

GlossaryA HR (Homologous Region) is a sequence that can recombine with the host genome. As explained for the integrative vector for E. coli, the passenger is the desired DNA part to be integrated into the genome. Design featuresThis vector backbone was designed as a modular integrative vector for S. cerevisiae. In this section, the main design features for vector engineering and for the genome integration of the vector are reported.

How to use it<partinfo>BBa_K300001</partinfo> can be:

How to propagate it before performing genome integrationThis vector can be easily propagated in E. coli thanks to the high-copy replication origin and the Ampicillin resistance selection marker, both derived from the <partinfo>pSB1A2</partinfo> vector backbone.

How to integrate a BioBrick into the yeast genome

Users can change the integration site by engineering the vector: <partinfo>BBa_K300986</partinfo> and <partinfo>BBa_K300987</partinfo> are flanked by two AvrII and two NheI respectively and for this reason the two Homologous Regions can be excided. New homologous sequences compatible with RFC10 can be digested with XbaI-SpeI and assembled because AvrII, NheI, XbaI and SpeI have compatible sticky ends. Note that this assembly is not directional and the correct orientation can be validated through sequencing with standard VF2 and VR primers.

How to perform the KanMX marker excisionThe KanMX dominant selection marker is flanked by two loxP recombination sites and for this reason it can be excided upon Cre recombinase activity (Fig.22). The Cre recombinase has to be expressed by a helper plasmid.

Self-cleaving affinity tags to easily purify proteinsConventional affinity-based protein purification methods rely on specific binding of the fusion tag to an immobilized ligand, but they are affected by severe limitations, as explained in the Motivation section. Briefly, they imply the use of expensive proteases for tag removal from the fusion protein, requiring the appropriate aminoacidic sequence to be included between the tag and the target protein. Moreover, the cost of the affinity resins used in the process is far from negligible, especially on industrial scale. The use of self-cleaving protein elements coupled with innovative affinity tags has been recently proposed to overcome these limitations. For all these reasons, in this section a technique compliant to the BioBrick assembly standard and based on self-splicing affinity tags derived from the fusion of Phasins, Inteins and a short flexible linker is proposed. TagPhasinPhasins are proteins involved in formation and stabilization of PolyHydroxyAlkanoates (PHA), intracytoplasmic inclusions in microorganisms like Ralstonia eutropha which serve as carbon and energy storage. As such, Phasins exhibit highly specific binding to PHA granules and can be used to create tags for proteins, while PHB can be used as the affinity matrix. In literature, it has also been shown that the Phasin-tagged fusion protein's affinity with PHA granules can be improved by increasing the number of Phasins in the fusion protein. The Ralstonia eutropha‘s Phasin coding sequence, <partinfo>K208001</partinfo>, was already present in the Registry in Silver standard. However, at the end of this gene there was a TGA stop codon which prevents the usage of this Phasin as a head or internal domain. In order to overcome this problem, <partinfo>K208001</partinfo> has been improved for fusion protein applications by mutagenesis through PCR using custom primers. Two new BioBrick parts were built and submitted to the Registry:

These two new parts allow the construction of composite synthetic affinity tags, built by assembling an arbitrary number of Phasins (it has been shown that a better affinity is achieved by fusing of two or more Phasins). In this work a flexible linker sequence (<partinfo>BBa_K105012</partinfo>) that connects the Phasins has also been used in order to test if it can improve or facilitate the binding and folding of the tag. PHA productionPHA production in R. eutropha is achieved by the PhaCAB operon, which contains three genes, phbC, phbA and phbB, each encoding for an enzyme essential for the formation of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB, a kind of polyhydroxyalkanoate) inclusions. In literature, the production of PHB has already been achieved in E. coli by incorporating the PhaCAB operon. The PHB granules produced by engineered E. coli can be used as an affinity matrix for Phasin-based affinity tags and the binding of the Phasin-tagged protein of interest can occur in vivo. Several parts for PHB production are present in the Registry: in the past iGEM editions, the Duke (2008 and 2009), Hawaii (2008), Tsinghua (2008), Virginia (2008) teams worked on it and submitted a set of BioBrick parts for PHB synthesis. However, the complete phaCAB operon is not available in the Registry. Because a lot of work about PHB has already been done and because our short term goal was not to optimize the PHB granules productions, an existing engineered E. coli strain able to produce PHB was used as a proof-of-concept affinity matrix producer. This strain comes from the DSMZ public collection and is named DMSZ15372. Taking advantage of the natural affinity of Phasins to PHB, it is possible to engineer strains in which PHB and the Phasin-tagged protein of interest are co-produced and the binding can occur. The overall yield and specificity of the process depends on the structure of the Phasin-based tags, which can be easily constructed or modified by using BioBrick parts compatible with the common RFC10 and RFC23 standards to perform in-frame assemblies. For this reason these tags are modular and can be freely expanded; a generic one is shown in Fig.23. Protein purification systemPhasins and PHB granules can replace the common affinity tags and matrix respectively. However, expensive proteases are still essential to remove the tag after the Phasins-PHB binding. A novel engineered inducible Intein can be used to complete the purification process by removing the affinity tag, thus replacing proteases. InteinInteins (Intervening Proteins) are sequences capable of self-exciding from a precursor protein through a process known as self-splicing, forming a peptide bond between the flanking proteins (exteins). Many so-called mini-Inteins have been engineered, whose key feature is the capability to completely release a flanking extein (the target protein) in response to a simple stimulus, either chemical or physical, with no need of expensive proteases. In literature, one mini-Intein was obtained through mutagenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mtu RecA Intein. The sequence of this Intein, referred to as ΔI-CM, allows for pH/heat-controlled C-terminal cleavage. Thanks to this feature, the ΔI-CM Intein can be fused downstream of an affinity tag and upstream of the protein coding sequence of interest in order to enable a cheap cleavage process to remove the N-terminal tag. In this project, the ΔI-CM Intein sequence was designed according to [Wood DW et al., 1999] and codon-optimized for E. coli to yield <partinfo>BBa_K300004</partinfo>. This part was designed as an internal domain (prefix and suffix compatible with Silver standard) in order to enable protein coding sequence assemblies to generate the desired synthetic self-cleavable affinity tags for protein purification. Thus, it is possible to create an engineered protein purification system that uses the tag construct and relies on Intein self-cleaving capabilities. Fig.24 shows a generic purification tag, composed by Phasins and Intein, as an example. Protein purification takes place as follows:

|

"

"