Team:Stockholm/Results/Assemblies

From 2010.igem.org

(New page: {{Stockholm/Results}}) |

|||

| (14 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Stockholm/Results}} | {{Stockholm/Results}} | ||

| + | {|width="800px" | ||

| + | |<div align="justify"> | ||

| + | {|align="right" | ||

| + | | width="265"| __TOC__ | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | ==Assemblies== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===IdeS·PtA-Z fusion protein=== | ||

| + | One of our approaches for protecting affected Vitiligo skin from autoantibodies was to locally digest IgG immunoglobulins using the IgG degrading bacterial protease IdeS. In an attempt to increase the efficiency of IdeS in the skin we suggested that IdeS be fused to the Z-domain of Protein A, which possesses the ability of binding to the Fc (constant) region of immunoglobulins. By combining the features of these two proteins, we could possibly create a protein chimera which binds with a high(er) affinity to IgG, thus increasing the protease's access to antibodies, resulting in a higher antibody degradation than native IdeS. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The PtA-Z·IdeS fusion protein was constructed as shown in the figure below:<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:PtA-Z IdeS fusion BioBrick.png|800px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===CPP fusions=== | ||

| + | As described in our project introduction, one of our aims was to target proteins to keratinocytes and melanocytes in human skin using cell-penetrating peptides. As we didn't know which of (or if) our CPPs would be most efficient in protein delivery, we set out to test all three in parallel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At least two of our CPPs (LMWP and Tp10) have not previously been tested using recombinant technique, i.e. in protein fusions. Although these have been shown to successfully deliver protein cargo into cells and/or skin, these proteins have been chemically conjugated to the CPPs, [[Image:PEX.his protein CPP.png|200px|thumb|right|'''Cloning strategy for proteins fused to CPPs''']] | ||

| + | [[Image:PEX.nCPP_protein_his.png|200px|thumb|right|'''Cloning strategy for proteins fused to N-part CPPs''']]usually to amino acid side chains. We were therefore unsure as to whether membrane and skin penetration would be most effective when fusing the CPPs to our proteins' N- or C-termini; we also discussed that this may possibly vary for different proteins, as different cargo properties may interact and possibly disturb our CPPs. In relation to this, we also discussed the probability of the CPPs disturbing the enzymatic activity of our fused cargo proteins, and whether this risk would differ depending on to which side of the protein (N- or C-terminus) the CPP is fused. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As time is very limited in the iGEM competition, and as we would not be able to test fusion to one side at the time, we decided to fuse the CPPs to both sides of our proteins, and draw our own conclusions by investigating both CPP and protein activity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another factor we took into consideration was the additional amino acids added to parts adapted to the [[http://partsregistry.org/Assembly_standard_25 Freiburg assembly standard]]. Due to the small size of our CPPs (11-21 a.a.) we thought that even a very small variation to the amino acid sequence could affect their function. For our N-terminal protein fusions we therefore designed N-part versions of our CPPs, which prevents the addition of the two extra amino acids in the CPP N-terminal (Ala & Gly) by removing the standard-specific NgoMIV restriction site. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, we also attached a 6x His tag to each one of our protein fusions to enable antibody detection and protein purification. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The figures to the right illustrate the cloning strategy for our CPP·protein fusions, and insertion into the IPTG-inducible protein expression pEX ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K243033 BBa_K243033]). Tables below show an overview of our many CPP·protein fusion combinations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {|border="1" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="3"|C-terminal CPP fusions | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center"|Purification tag | ||

| + | !align="center"|Protein | ||

| + | !align="center"|CPP | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |width="170" align="center"|<br /><br /><br />[[Image:His-tag_BioBrick.png|145px]] | ||

| + | |width="410" align="center"|[[Image:BFGF_BioBrick.png|245px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:SOD1_BioBrick.png|245px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:IdeS_BioBrick.png|380px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:ProteinA_BioBrick.png|215px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:PtA-Z_IdeS_fusion_BioBrick.png|400px]]<br /> | ||

| + | |width="220" align="center"|[[Image:TAT_BioBrick.png|170px]]<br /><br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:LMWP_BioBrick.png|175px]]<br /><br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:Tp10_BioBrick.png|180px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | <br /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | {|border="1" cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" | ||

| + | !align="center" colspan="3"|N-terminal CPP fusions | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | !align="center"|N-part CPP | ||

| + | !align="center"|Protein | ||

| + | !align="center"|Purification tag | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |width="220" align="center"|[[Image:nTAT_BioBrick.png|170px]]<br /><br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:nLMWP_BioBrick.png|175px]]<br /><br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:nTp10_BioBrick.png|180px]] | ||

| + | |width="410" align="center"|[[Image:BFGF_BioBrick.png|245px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:SOD1_BioBrick.png|245px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:IdeS_BioBrick.png|380px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:ProteinA_BioBrick.png|215px]]<br /> | ||

| + | [[Image:PtA-Z_IdeS_fusion_BioBrick.png|400px]]<br /> | ||

| + | |width="170" align="center"|<br /><br /><br />[[Image:His-tag_BioBrick.png|145px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Construction of a ''sod1''-''yccs'' operon=== | ||

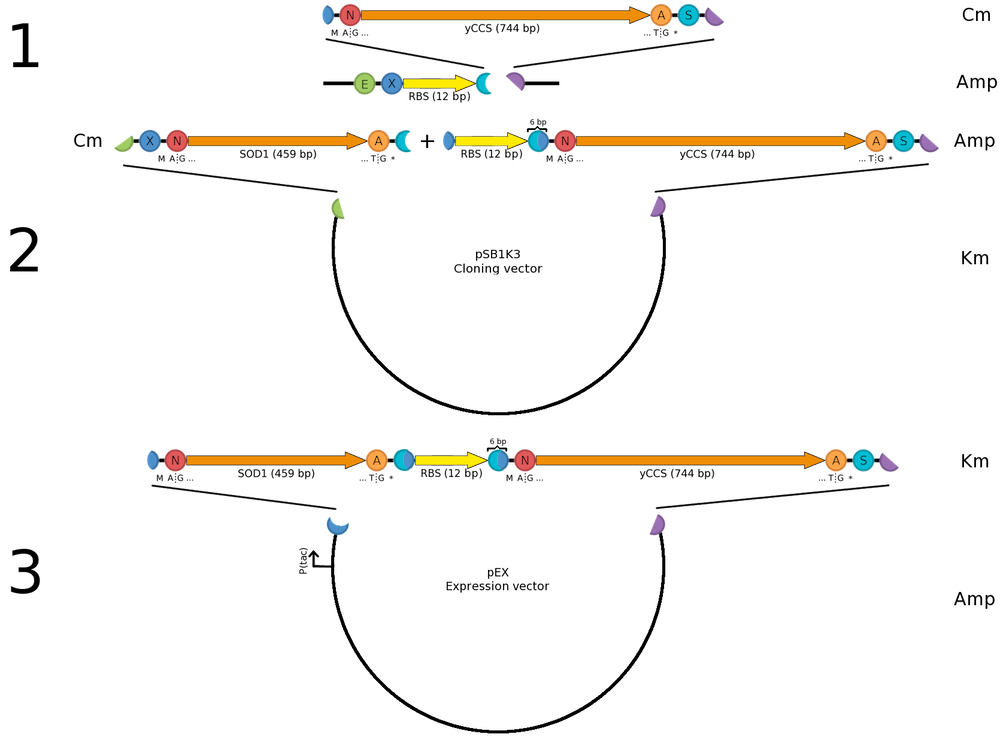

| + | [[Image:Sod yccs operon.png|200px|thumb|right|'''Cloning strategy for ''sod-yccs'' operon for co-expression in pEX.''']] | ||

| + | For SOD1 to be fully active it needs to be co-expressed with its helper copper chaperone, which provides SOD1 with necessary copper ions prior to folding. We are using a yeast copper chaperone (yCCS) for this. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since we were (for several reasons) restricted to the pEX vector for protein expression, we wanted construct a ''sod1''-''yccs'' operon allowing us to co-express the two genes from the same P<sub>tac</sub> promoter, which comes pre-installed in pEX. Previous studies (e.g. by [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15358352 Ahl ''et al.'' (2004)]) show that high copper content SOD1 is obtained with the protein is expressed in levels equal to yCCS. As we wanted to copy this behavior, transcription from the same promoter is an advantage. We then set out to look for a Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence with the same strength as the one found in pEX. Since no experimental comparison data with the pEX SD was available we chose the most similar with respect to (1) the ribosome-binding nucleotides and (2) distance to the start codon; thus we selected [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0034 BBa_B0034]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The operon was then assembled into pEX as illustrated. The same principle was used for constructing operons expressing CPP-SOD1 fusions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Stockholm/Footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:04, 27 October 2010

AssembliesIdeS·PtA-Z fusion proteinOne of our approaches for protecting affected Vitiligo skin from autoantibodies was to locally digest IgG immunoglobulins using the IgG degrading bacterial protease IdeS. In an attempt to increase the efficiency of IdeS in the skin we suggested that IdeS be fused to the Z-domain of Protein A, which possesses the ability of binding to the Fc (constant) region of immunoglobulins. By combining the features of these two proteins, we could possibly create a protein chimera which binds with a high(er) affinity to IgG, thus increasing the protease's access to antibodies, resulting in a higher antibody degradation than native IdeS. The PtA-Z·IdeS fusion protein was constructed as shown in the figure below: CPP fusionsAs described in our project introduction, one of our aims was to target proteins to keratinocytes and melanocytes in human skin using cell-penetrating peptides. As we didn't know which of (or if) our CPPs would be most efficient in protein delivery, we set out to test all three in parallel. At least two of our CPPs (LMWP and Tp10) have not previously been tested using recombinant technique, i.e. in protein fusions. Although these have been shown to successfully deliver protein cargo into cells and/or skin, these proteins have been chemically conjugated to the CPPs, usually to amino acid side chains. We were therefore unsure as to whether membrane and skin penetration would be most effective when fusing the CPPs to our proteins' N- or C-termini; we also discussed that this may possibly vary for different proteins, as different cargo properties may interact and possibly disturb our CPPs. In relation to this, we also discussed the probability of the CPPs disturbing the enzymatic activity of our fused cargo proteins, and whether this risk would differ depending on to which side of the protein (N- or C-terminus) the CPP is fused.As time is very limited in the iGEM competition, and as we would not be able to test fusion to one side at the time, we decided to fuse the CPPs to both sides of our proteins, and draw our own conclusions by investigating both CPP and protein activity. Another factor we took into consideration was the additional amino acids added to parts adapted to the http://partsregistry.org/Assembly_standard_25 Freiburg assembly standard. Due to the small size of our CPPs (11-21 a.a.) we thought that even a very small variation to the amino acid sequence could affect their function. For our N-terminal protein fusions we therefore designed N-part versions of our CPPs, which prevents the addition of the two extra amino acids in the CPP N-terminal (Ala & Gly) by removing the standard-specific NgoMIV restriction site. Finally, we also attached a 6x His tag to each one of our protein fusions to enable antibody detection and protein purification. The figures to the right illustrate the cloning strategy for our CPP·protein fusions, and insertion into the IPTG-inducible protein expression pEX ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K243033 BBa_K243033]). Tables below show an overview of our many CPP·protein fusion combinations.

Construction of a sod1-yccs operonFor SOD1 to be fully active it needs to be co-expressed with its helper copper chaperone, which provides SOD1 with necessary copper ions prior to folding. We are using a yeast copper chaperone (yCCS) for this. Since we were (for several reasons) restricted to the pEX vector for protein expression, we wanted construct a sod1-yccs operon allowing us to co-express the two genes from the same Ptac promoter, which comes pre-installed in pEX. Previous studies (e.g. by [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15358352 Ahl et al. (2004)]) show that high copper content SOD1 is obtained with the protein is expressed in levels equal to yCCS. As we wanted to copy this behavior, transcription from the same promoter is an advantage. We then set out to look for a Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence with the same strength as the one found in pEX. Since no experimental comparison data with the pEX SD was available we chose the most similar with respect to (1) the ribosome-binding nucleotides and (2) distance to the start codon; thus we selected [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0034 BBa_B0034]. The operon was then assembled into pEX as illustrated. The same principle was used for constructing operons expressing CPP-SOD1 fusions. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"

"