Team:Imperial College London/Modules/Detection

From 2010.igem.org

| (12 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

|style="font-family: helvetica, arial, sans-serif;font-size:2em;color:#ea8828;"|Detection Module | |style="font-family: helvetica, arial, sans-serif;font-size:2em;color:#ea8828;"|Detection Module | ||

|- | |- | ||

| - | | | + | | Having discussed with experts if ''Schistosoma'' cercaria would be the most useful lifecycle stage of ''Schistosoma'' to detect, we developed a surface protein that allows detection of ''Schistosoma'' in water. The key motivation for targeting the parasite larvae, called cercaria, is prevention of the disease altogether. The cercaria are often found in water, but their location as well as time of their appearance is unpredictable, putting the population in endemic areas at risk of infection. By providing a fast and reliable test, non-profit organisations would be able to regularly check the water for the presence of cercaria and warn people of the danger. Furthermore we are exploiting an essential aspect of the cercarias’ biochemistry without which they are unable to progress in their life cycle. To learn more about the parasite life cycle follow this link to our section on [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Imperial_College_London/Schistosoma ''' ''Schistosoma'' ''']. |

| - | + | |<div ALIGN=CENTER> | |

| + | {| style="width:354px;background:#e7e7e7;text-align:center;font-family: helvetica, arial, sans-serif;color:#555555;margin- top:5px;padding: 2px;" cellspacing="5"; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:IC_Detection2.JPG|350px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Overview of the detection module. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

__NOTOC__ | __NOTOC__ | ||

| - | + | |- | |

| + | |colspan="2"| | ||

'''Design''' | '''Design''' | ||

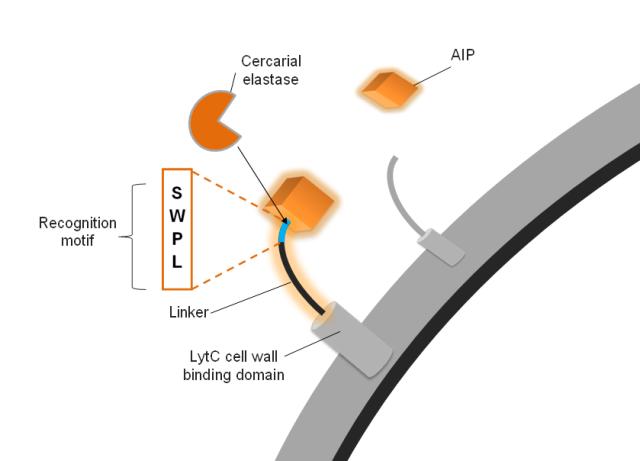

| - | We make use of a cercarial protease, called elastase [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P12546 '''(UniProt,'''] [http://merops.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/pepsum?id=S01.144 '''MEROPS)'''], necessary to penetrate human | + | We make use of a cercarial protease, called elastase [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P12546 '''(UniProt,'''] [http://merops.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/pepsum?id=S01.144 '''MEROPS)'''], which is necessary for cercaria to penetrate human. The surface our ''B. subtilis'' is coated with a surface protein which is design to release a sequestered quorum sensing signal upon cleavage by the elastase. |

| - | + | |- | |

| - | + | | | |

'''The AIP activates signal transduction''' | '''The AIP activates signal transduction''' | ||

| - | We used the autoinducing | + | We used the autoinducing peptide (AIP) from the ComCDE system of ''S. Pneumoniae'' because it is linear and lacks posttranslational modifications. Using a system foreign to ''B. subtilis'' also reduces false activation and the noise our system has to deal with, making it more robust. Because of the nature of the AIP receptor ComD, in order to activate signal transduction the AIP must be in the cleaved form, i.e. not attached to the surface protein anymore. This adds an additional level of robustness to the system. |

| - | + | | | |

| - | + | <div ALIGN=CENTER> | |

| + | {| style="width:354px;background:#e7e7e7;text-align:center;font-family: helvetica, arial, sans-serif;color:#555555;margin- top:5px;padding: 2px;" cellspacing="5"; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:IC_Detection.JPG|350px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |The detection module consists of three section: Cell Wall anchor, Linker and AIP | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |colspan="2"| | ||

'''The Linker is a substrate for the cercarial elastase''' | '''The Linker is a substrate for the cercarial elastase''' | ||

| - | The AIP is connected to a cell wall anchor via a linker. It is this linker that confers specificity to our surface protein to be cleaved by the elastase | + | The AIP is connected to a cell wall anchor via a linker. It is this linker that confers specificity to our surface protein which is to be cleaved by the elastase. The elastase itself recognises a four amino acid sequence, which we included in our linkers. In order to test the optimal design for the linker, we created 6 different linkers which vary in length and flexibility. Furthermore we created a do-it-yourself [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Imperial_College_London/Software_Tool '''Software Tool'''] which enables the custom design of the surface protein sequence to include a protease cleavage site of choice. This allows the detection of any protease by incorporating such new surface proteins into our system. |

'''Detection of Parasite proteases''' | '''Detection of Parasite proteases''' | ||

| - | In order to detect | + | In order to detect ''Schistosoma'' in water they have to release their elastase. This does not usually occur in the absence of a stimulus however it is easy to trigger this behaviour ''in vivo''. Upon detection of human (or mouse) skin lipids and temperatures close to 37°C, the invasive behaviour is triggered. Several proteases are released from pre- and postacetabular glands or the cercaria at the leading edge of the invading parasite. While multiple enzymes are released, only one protease activity was found to be necessary for invasion in ''S. mansoni'', and ''S. haematobium'' [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=JL7qs-O3z1MC&pg=PA299&lpg=PA299&dq=advances+in+parasitology+london&source=bl&ots=b8mvkz6zyC&sig=t7Pwy0egEDQ9dW-GIZEK7Pb6xxs&hl=en&ei=n05ATKLnJsqNjAePyOAG&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCEQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=advances%20in%20parasitology%20london&f=false (Kasny ''et al.'' 2009)]: Schistosoma elastase 2a and b (SmCE-1a/b) [http://www.jbc.org/content/277/27/24618.abstract (Salter ''et al.'' 2002)]. SmCE are trypsin family serine proteases the specificity of which has been investigated by various studies. It appears that the following cleavage sites are preferred: |

* P4 - S,T | * P4 - S,T | ||

* P3 - S,W,Y | * P3 - S,W,Y | ||

* P2 - P | * P2 - P | ||

* P1 - L | * P1 - L | ||

| - | Subtle differences exist between SmCE-2a and b as far as their P4 and P3 sites are concerned. Cleavage kinetics were determined for four different sites, P4-P1: SWPL, TWPL, RWPL, RRPL with R previously determined as unfavourable at P4 and P3. For P4 an 11-fold difference in activity was determined between favourable S/T and R, while a 3 fold difference was determined for P3 W to R [http://www.jbc.org/content/277/27/24618.abstract (Salter ''et al.'' 2002)]. The most favourable sequence would therefore be SWPL. | + | Subtle differences exist between SmCE-2a and b as far as their P4 and P3 sites are concerned. Cleavage kinetics were determined for four different sites, P4-P1: SWPL, TWPL, RWPL, RRPL with R previously determined as unfavourable at P4 and P3. For P4 an 11-fold difference in activity was determined between favourable S/T and R, while a 3-fold difference was determined for P3 W to R [http://www.jbc.org/content/277/27/24618.abstract (Salter ''et al.'' 2002)]. The most favourable sequence would therefore be SWPL. |

| - | + | <html> | |

| - | + | <table width="300px" border="0" align=center> | |

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#FFCC66;height:50px;width:50;text-align:center"><b>Uniprot accession</b></td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#FFCC66;height:50px;width:50;text-align:center"><b>MEROPS ID</b></td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#FFCC66;height:50px;width:50;text-align:center"><b>Clan</b></td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#FFCC66;height:50px;width:50;text-align:center"><b>Family</b></td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#FFCC66;height:50px;width:50;text-align:center"><b>pH optimum</b></td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#FFCC66;height:50px;width:50;text-align:center"><b>Molecular weight (practical/theoretical)</b></td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#eeeeee;height:50px;width:50 px;text-align:center;">P12546</td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#eeeeee;height:50px;width:50 px;text-align:center;">S01.144</td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#eeeeee;height:50px;width:50 px;text-align:center;">PA(S)</td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#eeeeee;height:50px;width:50 px;text-align:center;">S1</td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#eeeeee;height:50px;width:50 px;text-align:center;">4-10.5</td> | ||

| + | <td style="background-color:#eeeeee;height:50px;width:50 px;text-align:center;">25/29 kDA</td> | ||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | </html> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| - | + | |'''The cell wall binding domain anchors our module to the cell surface''' | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | | | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | |||

| - | + | The AIP-linker peptide is anchored to the cell wall by LytC, a protein native to ''B. subtilis'. The process of anchoring the recombinant protein to the cell wall helps to increase the efficiency of detection. It uses electrostatic interactions of several cell wall binding domain repeats to non-covalently bind to the cell wall, and expose our detection apparatus to the elastase. We chose it over other options, such as covalently bound proteins that use the Gram positive sortase system, membrane bound proteins or other non-covalently bound cell wall proteins for several reasons. Firstly, we wanted to minimise the chance of false activation of signal transduction, so we eliminated cell membrane bound proteins, as these would bring the AIP in much greater proximity to the receptor ComD. Whilst the sortase system is well understood for some bacteria such as ''Staphylococcus aureus'', it has not been extensively studies in ''B. subtilis'' and differences in the peptidoglycan structure meant it would have been much more error prone to use this system in our chassis. Thus the most viable option were non-covalently bound surface proteins, and LytC the best candidate within this group as a result of several studies, most notably by Kobayashi et al. (2003), that had previously used it to anchor catalytic domains, as well as short peptides, to the cell wall of ''B. subtilis''. | |

| - | |||

| + | [http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119078114/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0 Tsuchiya et al. 1999] | ||

| - | + | [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VSD-426YS50-D&_user=217827&_coverDate=12%2F31%2F2000&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000011279&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=217827&md5=4764a7bdabc3649925f082f989e835f5 Kobayashi et al. 2000] | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VSD-46G3T2V-4&_user=217827&_coverDate=01%2F31%2F2002&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000011279&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=217827&md5=c807c9de3e3579777b08fdd77cd32294 Kobayashi et al. 2002] | ||

| - | Additionally, since we do not intend to knock out the original gene from the ''B. subtilis'' strain we will not interfere with | + | [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/reprint/185/22/6666 Yamamoto et al. 2003] |

| - | + | | | |

| - | + | <div ALIGN=CENTER> | |

| - | + | {| style="width:254px;background:#e7e7e7;text-align:center;font-family: helvetica, arial, sans-serif;color:#555555;margin- top:5px;padding: 2px;" cellspacing="5"; | |

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Picture1.png|250px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Crystal structure the protein LytC used to anchor our peptide to the cell wall. (EBI, 2010) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |colspan="2"| | ||

| + | Additionally, since we do not intend to knock out the original gene from the ''B. subtilis'' strain we will not interfere with its normal expression, avoiding expression at the wrong time or over expression. Furthermore since we aim to remove the catalytic domain from LytC or CwlC, our fusion proteins should lose their cell wall turn-over functions and only act as cell wall anchors. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

'''Summary and Testing''' | '''Summary and Testing''' | ||

| - | Before | + | Before finalising our system we modelled the requirements for our detection module to analyse its functionality. For more information on this follow this link to our [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Imperial_College_London/Modelling/Protein_Display/Objectives '''Modelling''']. It showed that we could reach the threshold concentration of AIP needed to activate our system, 10ng/ml, quite easily, with the amount of surface protein we expect to express, as well as estimating the time needed to set off our system at a given concentration of elastase in the water. |

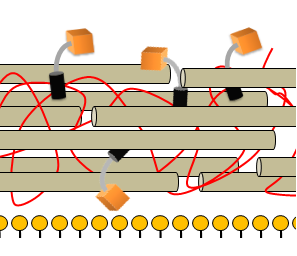

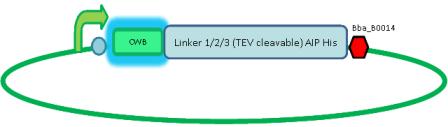

| - | The assembly of the protein was done in several steps. We first amplified LytC out of the B. subtilis genome by PCR, simultaneously using primer extension to add optimised ribosome binding sites to it, and | + | The assembly of the protein was done in several steps. We first amplified LytC out of the ''B. subtilis'' genome by PCR, simultaneously using primer extension to add optimised ribosome binding sites to it, and insert the PCR product into pSB1C3. We later ligated the protein with the promoter Pveg. Parallel to this, we ligated the 6 linker sequences ordered from Eurofins|mwg with a double terminator BOO14. We then made use of a natural ACCI site in the LytC gene, to ligate our promoter-LytC sequence with our linker-terminator sequence to create 6 different surface protein constructs, for testing in ''B. subtilis''. |

| - | In order to be able to detect out protein use His-tags | + | |<div ALIGN=CENTER> |

| + | {| style="width:354px;background:#e7e7e7;text-align:center;font-family: helvetica, arial, sans-serif;color:#555555;margin- top:5px;padding: 2px;" cellspacing="5"; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:Picture2Cell_wall_with_detection_module.png|350px]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |The detection module is non-covalently bound to the cell wall that overlies the phospholipid bilayer | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |colspan="2"| | ||

| + | In order to be able to detect out protein we will use His-tags. However these are only been added to test constructs and not the final module, as the tag would most likely interfere with the module’s function. The his-tags have been added to the C-terminus of the AIP, probably inhibiting correct detection of the AIP by the two component system comD/E. However using a his-tag allows us to test for three different, very important things: We can lyse a bacterial culture to isolate our his-tagged protein from the lysate. Detection in this step would demonstrate successful expression of our fusion protein. Secondly we can place our bacteria in a solution with high osmolarity. As mentioned this eludes the non-covalently bound proteins from the cell wall by interfering with the electrostatic interactions of the cell wall binding domain with the peptidoglycans, which should also work for our fusion proteins. Detection of our protein in this step would demonstrate expression as well as correct localisation in the cell wall. Last of all we could place the cells in medium containing the elastase or a protease with the same or very similarly specificity. If we are able to pull down the his-tagged peptide then it would demonstrate expression, localisation and that the correct cleavage site is accessible to the protease and the AIP can be successfully cleaved off. For a complete list of the BioBrick created for this module see our page on [https://2010.igem.org/Team:Imperial_College_London/Parts '''Parts'''] submitted to the registry. | ||

Here's a picture of the final construct: | Here's a picture of the final construct: | ||

| - | [[Image:IC_Module1.JPG | + | <div ALIGN=CENTER> |

| + | {| style="background:#e7e7e7;text-align:center;font-family: helvetica, arial, sans-serif;color:#555555;margin- top:5px;padding: 2px;" cellspacing="5"; | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |[[Image:IC_Module1.JPG|500px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </div> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:08, 28 October 2010

| Modules | Overview | Detection | Signaling | Fast Response |

| Our design consists of three modules; Detection, Signaling and a Fast Response, each of which can be exchanged with other systems. We used a combination of modelling and human practices to define our specifications. Take a look at the overview page to get a feel for the outline, then head to the full module pages to find out how we did it. | |

| Detection Module | |||||||||||||

| Having discussed with experts if Schistosoma cercaria would be the most useful lifecycle stage of Schistosoma to detect, we developed a surface protein that allows detection of Schistosoma in water. The key motivation for targeting the parasite larvae, called cercaria, is prevention of the disease altogether. The cercaria are often found in water, but their location as well as time of their appearance is unpredictable, putting the population in endemic areas at risk of infection. By providing a fast and reliable test, non-profit organisations would be able to regularly check the water for the presence of cercaria and warn people of the danger. Furthermore we are exploiting an essential aspect of the cercarias’ biochemistry without which they are unable to progress in their life cycle. To learn more about the parasite life cycle follow this link to our section on Schistosoma . | |||||||||||||

|

Design We make use of a cercarial protease, called elastase [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P12546 (UniProt,] [http://merops.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/pepsum?id=S01.144 MEROPS)], which is necessary for cercaria to penetrate human. The surface our B. subtilis is coated with a surface protein which is design to release a sequestered quorum sensing signal upon cleavage by the elastase. | |||||||||||||

|

The AIP activates signal transduction We used the autoinducing peptide (AIP) from the ComCDE system of S. Pneumoniae because it is linear and lacks posttranslational modifications. Using a system foreign to B. subtilis also reduces false activation and the noise our system has to deal with, making it more robust. Because of the nature of the AIP receptor ComD, in order to activate signal transduction the AIP must be in the cleaved form, i.e. not attached to the surface protein anymore. This adds an additional level of robustness to the system. | |||||||||||||

|

The Linker is a substrate for the cercarial elastase The AIP is connected to a cell wall anchor via a linker. It is this linker that confers specificity to our surface protein which is to be cleaved by the elastase. The elastase itself recognises a four amino acid sequence, which we included in our linkers. In order to test the optimal design for the linker, we created 6 different linkers which vary in length and flexibility. Furthermore we created a do-it-yourself Software Tool which enables the custom design of the surface protein sequence to include a protease cleavage site of choice. This allows the detection of any protease by incorporating such new surface proteins into our system.

In order to detect Schistosoma in water they have to release their elastase. This does not usually occur in the absence of a stimulus however it is easy to trigger this behaviour in vivo. Upon detection of human (or mouse) skin lipids and temperatures close to 37°C, the invasive behaviour is triggered. Several proteases are released from pre- and postacetabular glands or the cercaria at the leading edge of the invading parasite. While multiple enzymes are released, only one protease activity was found to be necessary for invasion in S. mansoni, and S. haematobium [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=JL7qs-O3z1MC&pg=PA299&lpg=PA299&dq=advances+in+parasitology+london&source=bl&ots=b8mvkz6zyC&sig=t7Pwy0egEDQ9dW-GIZEK7Pb6xxs&hl=en&ei=n05ATKLnJsqNjAePyOAG&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCEQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=advances%20in%20parasitology%20london&f=false (Kasny et al. 2009)]: Schistosoma elastase 2a and b (SmCE-1a/b) [http://www.jbc.org/content/277/27/24618.abstract (Salter et al. 2002)]. SmCE are trypsin family serine proteases the specificity of which has been investigated by various studies. It appears that the following cleavage sites are preferred:

Subtle differences exist between SmCE-2a and b as far as their P4 and P3 sites are concerned. Cleavage kinetics were determined for four different sites, P4-P1: SWPL, TWPL, RWPL, RRPL with R previously determined as unfavourable at P4 and P3. For P4 an 11-fold difference in activity was determined between favourable S/T and R, while a 3-fold difference was determined for P3 W to R [http://www.jbc.org/content/277/27/24618.abstract (Salter et al. 2002)]. The most favourable sequence would therefore be SWPL.

| |||||||||||||

| The cell wall binding domain anchors our module to the cell surface

The AIP-linker peptide is anchored to the cell wall by LytC, a protein native to B. subtilis'. The process of anchoring the recombinant protein to the cell wall helps to increase the efficiency of detection. It uses electrostatic interactions of several cell wall binding domain repeats to non-covalently bind to the cell wall, and expose our detection apparatus to the elastase. We chose it over other options, such as covalently bound proteins that use the Gram positive sortase system, membrane bound proteins or other non-covalently bound cell wall proteins for several reasons. Firstly, we wanted to minimise the chance of false activation of signal transduction, so we eliminated cell membrane bound proteins, as these would bring the AIP in much greater proximity to the receptor ComD. Whilst the sortase system is well understood for some bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, it has not been extensively studies in B. subtilis and differences in the peptidoglycan structure meant it would have been much more error prone to use this system in our chassis. Thus the most viable option were non-covalently bound surface proteins, and LytC the best candidate within this group as a result of several studies, most notably by Kobayashi et al. (2003), that had previously used it to anchor catalytic domains, as well as short peptides, to the cell wall of B. subtilis.

[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VSD-426YS50-D&_user=217827&_coverDate=12%2F31%2F2000&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000011279&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=217827&md5=4764a7bdabc3649925f082f989e835f5 Kobayashi et al. 2000] [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VSD-46G3T2V-4&_user=217827&_coverDate=01%2F31%2F2002&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000011279&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=217827&md5=c807c9de3e3579777b08fdd77cd32294 Kobayashi et al. 2002] [http://jb.asm.org/cgi/reprint/185/22/6666 Yamamoto et al. 2003] | |||||||||||||

|

Additionally, since we do not intend to knock out the original gene from the B. subtilis strain we will not interfere with its normal expression, avoiding expression at the wrong time or over expression. Furthermore since we aim to remove the catalytic domain from LytC or CwlC, our fusion proteins should lose their cell wall turn-over functions and only act as cell wall anchors. | |||||||||||||

|

Summary and Testing Before finalising our system we modelled the requirements for our detection module to analyse its functionality. For more information on this follow this link to our Modelling. It showed that we could reach the threshold concentration of AIP needed to activate our system, 10ng/ml, quite easily, with the amount of surface protein we expect to express, as well as estimating the time needed to set off our system at a given concentration of elastase in the water. The assembly of the protein was done in several steps. We first amplified LytC out of the B. subtilis genome by PCR, simultaneously using primer extension to add optimised ribosome binding sites to it, and insert the PCR product into pSB1C3. We later ligated the protein with the promoter Pveg. Parallel to this, we ligated the 6 linker sequences ordered from Eurofins|mwg with a double terminator BOO14. We then made use of a natural ACCI site in the LytC gene, to ligate our promoter-LytC sequence with our linker-terminator sequence to create 6 different surface protein constructs, for testing in B. subtilis. | |||||||||||||

|

In order to be able to detect out protein we will use His-tags. However these are only been added to test constructs and not the final module, as the tag would most likely interfere with the module’s function. The his-tags have been added to the C-terminus of the AIP, probably inhibiting correct detection of the AIP by the two component system comD/E. However using a his-tag allows us to test for three different, very important things: We can lyse a bacterial culture to isolate our his-tagged protein from the lysate. Detection in this step would demonstrate successful expression of our fusion protein. Secondly we can place our bacteria in a solution with high osmolarity. As mentioned this eludes the non-covalently bound proteins from the cell wall by interfering with the electrostatic interactions of the cell wall binding domain with the peptidoglycans, which should also work for our fusion proteins. Detection of our protein in this step would demonstrate expression as well as correct localisation in the cell wall. Last of all we could place the cells in medium containing the elastase or a protease with the same or very similarly specificity. If we are able to pull down the his-tagged peptide then it would demonstrate expression, localisation and that the correct cleavage site is accessible to the protease and the AIP can be successfully cleaved off. For a complete list of the BioBrick created for this module see our page on Parts submitted to the registry.

|

|||||||||||||

"

"