Team:Nevada/plant compatible reporters

From 2010.igem.org

(→Reporters) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

<div style="padding: 10px 10px 30px 10px;"> | <div style="padding: 10px 10px 30px 10px;"> | ||

| - | + | <p> </p> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

== Reporters == | == Reporters == | ||

https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/9/98/Finished_final.png | https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/9/98/Finished_final.png | ||

| Line 17: | Line 13: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

| - | + | <html> | |

<a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/7/7e/Reporters.png"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/7/7e/Reporters.png" class="shadow" style="float:left;width:450px;margin:10px"></a> | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/7/7e/Reporters.png"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2010/7/7e/Reporters.png" class="shadow" style="float:left;width:450px;margin:10px"></a> | ||

| - | </html | + | </html> |

| - | |||

| - | <p> | + | <p style="text-align:center;"><span style="text-decoration:underline;font-weight:bold">Building Consensus</span></p> |

| - | + | While all the aforementioned issues are important, the aspect of plant engineering that we believe is fundamental for future iGEM teams to consider is the ribosome binding site (RBS). RBS can differ between species, but it varies widely between eukaryotes, such as yeast, animals, and plants. The term RBS can be misleading because ribosomes can weakly associate with RNA as it “scans” along the sequence. Why is the ribosome “scanning?” Ribosomes initiate translation, and the “start” site that we have all been taught for eukaryotes is the methionine sequence AUG (or ATG if you are biased towards DNA). However, almost thirty years ago, a researcher named Kozak discovered that it is not simply AUG which initiates translation but the context of that AUG, the surrounding sequence, influenced whether translation actually began with one AUG sequence versus another. These context sequences, as they have been discovered in different organisms, eventually have been named Kozak sequences. | |

| - | ''' | + | Even among plants, there can be different Kozak sequences. Where we decided to contribute to iGEM was to supply the registry with the first fluorescent proteins with plant compatible RBS or Kozak sequences. We have chosen a generically ‘strong’ Kozak sequence that should provide the maximum translational efficiency for dicots, but it should also work generally well enough in most if not all plants. Our sequence is AAA AAA AAA ACA upstream of the AUG. An important aspect of Kozak sequences one should consider is there are both an upstream component and a downstream component. The string of purines upstream is associated with many plant Kozak sequences, but almost equally important is to have a G at the +4 position, or immediately following the AUG. Therefore, AAAAAAAAACA'''AUG'''G is likely to have the highest translational efficiency. Fortunately, two of the florescent proteins, EYFP and mCherry have this context. GFP, however, does not. It is missing the G at +4, which will hurt its translational efficiency. Instead, a C occupies that position which codes for arginine, R. There is no codon for arginine that starts with G. Unless a known mutation can be made, we may stuck with that hindrance. However, we have attempted to compensate in one of our composite parts, 35S GFP. 35S is a constitutive plant promoter. Ideally, the high transcriptional activity can compensate for the weakened translational efficiency. |

| - | + | <p> </p> | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | ---- | ||

| + | <p style="text-align:center;"><span style="text-decoration:underline;font-weight:bold">Engineering Possibilities (Fine tuning your translation)</span></p> | ||

As we see it, there are three ways future iGEM teams could engage the plant Kozak sequence to modify gene expression in plants: identity, distance, or deking. | As we see it, there are three ways future iGEM teams could engage the plant Kozak sequence to modify gene expression in plants: identity, distance, or deking. | ||

| - | '''1)Identity''': The most obvious way of affecting translational efficiency would be to alter the Kozak sequences. Having genes each prefaced with the same promoter but with different Kozak contextual sequences would tier the levels of expression. One could have an optimum Kozak like the one we have submitted and also engineer a weaker Kozak sequence for another gene which has relatively 50% expression compared to the optimum gene expressed. Consulting literature or experimenting in less-frequently researched plants will allow for greater variability in controlling expression. | + | '''1) Identity''': The most obvious way of affecting translational efficiency would be to alter the Kozak sequences. Having genes each prefaced with the same promoter but with different Kozak contextual sequences would tier the levels of expression. One could have an optimum Kozak like the one we have submitted and also engineer a weaker Kozak sequence for another gene, which has relatively 50% expression, compared to the optimum gene expressed. Consulting literature or experimenting in less-frequently researched plants will allow for greater variability in controlling expression. |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| + | '''2) Distance''': Another way to affect your protein expression would be how far the ‘true’ Kozak sequence is relative to the 5’ cap. A strong Kozak sequence means nothing if it is several hundred base pairs away from the end of the promoter. Because our team wanted to supply genes with maximal expression, our parts are intended to be placed immediately behind the promoter. Yet, engineering plasmids that put gaps between the promoter and actual Kozak, or primers designed to put more space in between the promoter and start site, could also be one way of dialing the levels of expression. | ||

| + | '''3) Deking''':(Realizing a team from a desert is using a hockey term): The “fake out.” A third alternative that combines the principles of identity and distance is to create one, two, or a few pseudo-start sites. A Psuedo-start sites means one would engineer AUG sequences upstream of the actual, desired one. These sequences would be in a poorer context and/or would translate into little nonsense peptides that theoretically have no function. Think of them as siAUG (short interfering AUG sites). These fake sites would knockdown expression. | ||

| + | In Summary, Kozak sequences have plenty of promise in the engineering side of iGEM, but Kozak sequences are also a necessity that all iGEM teams must consider if they are to express proteins in plants. | ||

| + | <span style="text-decoration:underline;font-weight:bold">References</span> | ||

| + | '''Agarwal, S., Jha, S., Sanyal, I., Amla, D.V.''' (2009) Effect of point mutations in translation initiation context on the expression of recombinant human alpha1-proteinase inhibitor in transgenic tomato plants. ''Plant Cell Reports''. 28: 1791-1798. | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | '''Joshi, C.P., Zhou, H., Huang, X., Chiang, V.L.''' (1997) Context sequences of translation initiation codon in plants. ''Plant Molecular Biology''. 35: 993-1001. | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | '''Kozak, M.''' (1986) Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribososomes. ''Cell''. 44: 283-92. | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | '''Matsuda, D., Dreher, T.W.''' (2006) Close spacing of AUG initiation codons confers dicistronic character on a eukaryotic mRNA. ''RNA''. 12: 1138-1349. | ||

| Line 60: | Line 55: | ||

!align="center"|[[Image:Promega_logo.jpg]] | !align="center"|[[Image:Promega_logo.jpg]] | ||

!align="center"|[[Image:Invitrogen_logo.jpeg]] | !align="center"|[[Image:Invitrogen_logo.jpeg]] | ||

| - | + | !align="center"|[[Image:Sda logo small.jpg]] | |

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 19:32, 27 October 2010

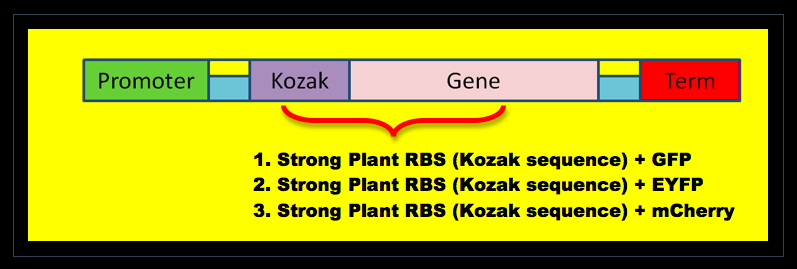

Reporters

- Strong Plant RBS (Kozak sequence) + GFP from E0040 Team:Nevada/registry submissions

- Strong Plant RBS (Kozak sequence) + EYFP from E0030 Team:Nevada/registry submissions

- Strong Plant RBS (Kozak sequence) + mCherry from J06504 Team:Nevada/registry submissions

Building Consensus

While all the aforementioned issues are important, the aspect of plant engineering that we believe is fundamental for future iGEM teams to consider is the ribosome binding site (RBS). RBS can differ between species, but it varies widely between eukaryotes, such as yeast, animals, and plants. The term RBS can be misleading because ribosomes can weakly associate with RNA as it “scans” along the sequence. Why is the ribosome “scanning?” Ribosomes initiate translation, and the “start” site that we have all been taught for eukaryotes is the methionine sequence AUG (or ATG if you are biased towards DNA). However, almost thirty years ago, a researcher named Kozak discovered that it is not simply AUG which initiates translation but the context of that AUG, the surrounding sequence, influenced whether translation actually began with one AUG sequence versus another. These context sequences, as they have been discovered in different organisms, eventually have been named Kozak sequences.

Even among plants, there can be different Kozak sequences. Where we decided to contribute to iGEM was to supply the registry with the first fluorescent proteins with plant compatible RBS or Kozak sequences. We have chosen a generically ‘strong’ Kozak sequence that should provide the maximum translational efficiency for dicots, but it should also work generally well enough in most if not all plants. Our sequence is AAA AAA AAA ACA upstream of the AUG. An important aspect of Kozak sequences one should consider is there are both an upstream component and a downstream component. The string of purines upstream is associated with many plant Kozak sequences, but almost equally important is to have a G at the +4 position, or immediately following the AUG. Therefore, AAAAAAAAACAAUGG is likely to have the highest translational efficiency. Fortunately, two of the florescent proteins, EYFP and mCherry have this context. GFP, however, does not. It is missing the G at +4, which will hurt its translational efficiency. Instead, a C occupies that position which codes for arginine, R. There is no codon for arginine that starts with G. Unless a known mutation can be made, we may stuck with that hindrance. However, we have attempted to compensate in one of our composite parts, 35S GFP. 35S is a constitutive plant promoter. Ideally, the high transcriptional activity can compensate for the weakened translational efficiency.

Engineering Possibilities (Fine tuning your translation)

As we see it, there are three ways future iGEM teams could engage the plant Kozak sequence to modify gene expression in plants: identity, distance, or deking.

1) Identity: The most obvious way of affecting translational efficiency would be to alter the Kozak sequences. Having genes each prefaced with the same promoter but with different Kozak contextual sequences would tier the levels of expression. One could have an optimum Kozak like the one we have submitted and also engineer a weaker Kozak sequence for another gene, which has relatively 50% expression, compared to the optimum gene expressed. Consulting literature or experimenting in less-frequently researched plants will allow for greater variability in controlling expression.

2) Distance: Another way to affect your protein expression would be how far the ‘true’ Kozak sequence is relative to the 5’ cap. A strong Kozak sequence means nothing if it is several hundred base pairs away from the end of the promoter. Because our team wanted to supply genes with maximal expression, our parts are intended to be placed immediately behind the promoter. Yet, engineering plasmids that put gaps between the promoter and actual Kozak, or primers designed to put more space in between the promoter and start site, could also be one way of dialing the levels of expression.

3) Deking:(Realizing a team from a desert is using a hockey term): The “fake out.” A third alternative that combines the principles of identity and distance is to create one, two, or a few pseudo-start sites. A Psuedo-start sites means one would engineer AUG sequences upstream of the actual, desired one. These sequences would be in a poorer context and/or would translate into little nonsense peptides that theoretically have no function. Think of them as siAUG (short interfering AUG sites). These fake sites would knockdown expression.

In Summary, Kozak sequences have plenty of promise in the engineering side of iGEM, but Kozak sequences are also a necessity that all iGEM teams must consider if they are to express proteins in plants.

References

Agarwal, S., Jha, S., Sanyal, I., Amla, D.V. (2009) Effect of point mutations in translation initiation context on the expression of recombinant human alpha1-proteinase inhibitor in transgenic tomato plants. Plant Cell Reports. 28: 1791-1798.

Joshi, C.P., Zhou, H., Huang, X., Chiang, V.L. (1997) Context sequences of translation initiation codon in plants. Plant Molecular Biology. 35: 993-1001.

Kozak, M. (1986) Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribososomes. Cell. 44: 283-92.

Matsuda, D., Dreher, T.W. (2006) Close spacing of AUG initiation codons confers dicistronic character on a eukaryotic mRNA. RNA. 12: 1138-1349.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

"

"