Team:ETHZ Basel/Modeling/Movement

From 2010.igem.org

Modeling & Simulating Bacterial Movement

While the biologists are busy teaching the E. coli how to respond to light, the modelers thought of simulating the light driven E. coli electronically. This will close the loop of our virtual E.lemming and will help us check the imaging pipeline, microscope analysis & joystick control even without actually having the real E. lemming under the microscope.

Overview

Analogous to the highly complex signal transduction in the Chemotaxis receptor model, there is an equally challenging molecular mechanism on side of the flagella, responsible for the movement of the bacterium.

In order to capture the realistic features of cell motility under Chemotaxis, we implemented a probabilistic model, which performs in accordance to the existing empirical observations on Chemotaxis movement. At every time point of the simulation, CheYp concentration is received as an input from the Chemotaxis pathway model. This input determines the direction (CCW or CW) of rotation of the flagellar motor. A counterclockwise rotation corresponds to the running state and to a change in spatial coordinates, together with a slight change in angle, while a clockwise rotation corresponds to the tumbling state and to an angle change, with unchanged spatial coordinates.

The coupling of the probabilistic movement model with the molecular model ensures that we can realistically simulate the variations in the motility with the variations in the protein concentrations.

Concepts

The main concepts we used in deriving and implementing our model are based on the most important features observed in the real behavior of E.coli. These features are:

Bias

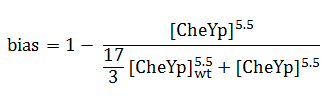

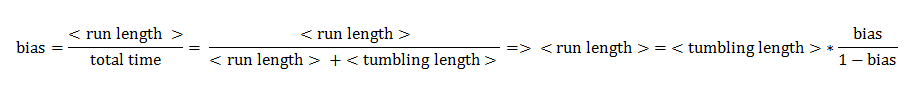

The link between CheYp concentration and the type of movement chosen by the bacterium is called bias and it is formally defined as the fraction of time spent in the running state with respect to the total observation time. Our choice for bias formulation was a nonlinear Hill - type function of the CheYp concentration, with one of the parameters being the wild - type CheYp concentration for which a steady - state bias value was obtained. Both the functional dependency and CheYp value are well documented from the literature side [2].

At every time point of the simulation, the cell probabilistically chooses whether to run or to tumble, depending on the bias value. The choice of the running state is equivalent to a change in spatial coordinates, together with a slight change in direction (movement angle), while the choice of the tumbling state corresponds to new movement angle and unchanged spatial coordinates.

Mean times

An important way of characterizing the cell's behavior is by statistically observing it over a longer time period.

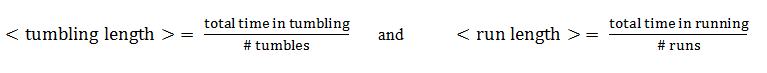

From this aspect, the mean tumbling length is the average time the cell spends in between two runs, while the mean run length is the average time spent in the running state.

Tumbling angle

The tumbling angle is the change of direction from run to run. We approximated the empirically observed distribution with a Weibull distribution (right panel), with same mean and variance as the empirically observed ones.

Transition Probabilities

One of the biggest challenges regarding the movement model was obtaining a time - step - invariant behavior of the cell, whose reliability of statistical estimates should be the same, regardless of how often the cell had to choose its future state.

In order to achieve this, we opted for a two - state first - order Markov process, in which the future state is only dependent on the current state. Since we have boolean values for any possible state, we can define the following four transition probabilities, separately controlled depending on whether the cell is currently running or tumbling.

| Running | Tumbling | |

| Running | p1 | 1 - p1 |

| Tumbling | 1 - p2 | p2 |

Therefore, the two central parameters of our model are the probabilities of keeping the current state also as future state: the probability of the future state being running, when the current state is running (p1) and probability of the future state being tumbling, when the current state is tumbling (p2).

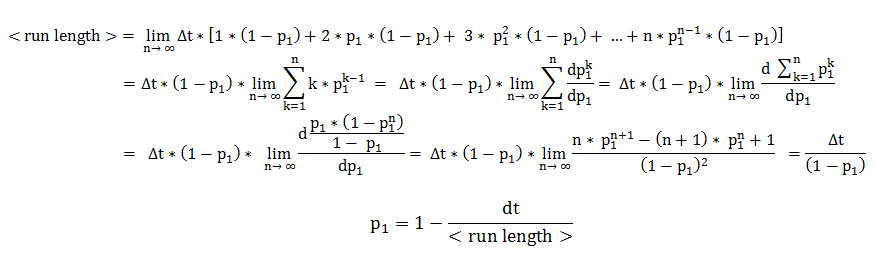

In deriving the expression of these probabilities, we separately and symmetrically focused on the two processes: running and tumbling. As a consequence, the mean running length is only dependent on the timestep and on the probability of continuing running (p1), while the mean tumbling length is only dependent on the timestep and on the probability of continuing tumbling (p2).

We will explain in detail the technique employed in deriving the probability of running, when the previous state was running. The symmetrical calculations, for the mean tumbling length, follow identically.

The mean running length is the expected value of a random variable representing the number of timesteps the cell consecutively spends in running. By expanding the definition of an expected value, the mean running length becomes an infinite sum over all possible consecutive running-lengths, multiplied by their respective occurrence probabilities.

Assumptions

The assumptions of our model were taken in accordance with the existing experimental data on the chemotaxis movement [1]. The mean tumbling length was assumed to be constant, unlike the mean running length, which is a function of the bias. Besides the experimental evidence, this assumption also has a biological interpretation: tumbling is believed to occur because the flagella push each other away and disassemble after rotating counter-clock wise (running). The duration spend in tumbling is a stochastic variable mainly representing the time the flagella afterwards need to reassemble, and a single process of reassembling is only weakly correlated with the frequency of tumbling.

Furthermore we assumed that the mean velocity during runs is constant.

Algorithm

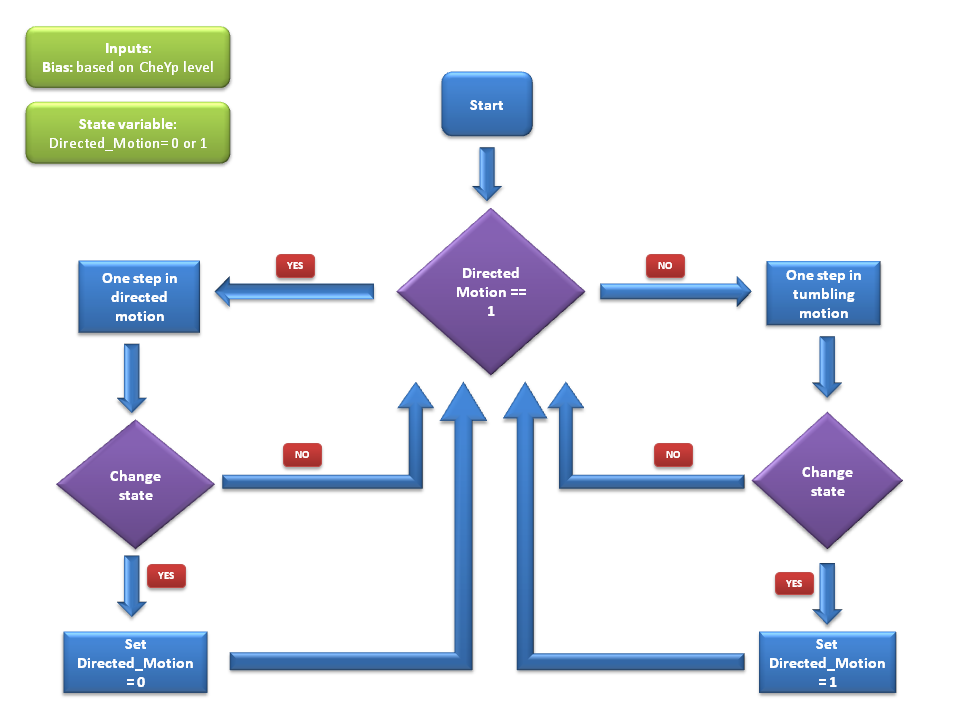

We use a two state model that reflects the two states the cell can be in through out its motion - swimming state & the tumbling state. At each time-step of the simulation, the cell will either stay in the same state or will switch the state according to these probabilities. Details of these probability values can be found below.

In each of these states, there is a transition probability to switch to the other states. As described above, we have the probability P1 that tells us the probability of switching to the tumbling state when the cell is currently in the swimming state and also the probability P2 that that reflects the probability of switching to the running state. At each timestep, the decision whether to run or tumble in the next timestep is taken based on these two probabilities.

If the decision was to run in the next timestep, the cell will be moved to it's next point with a velocity that agrees with literature [1]. Also, there is a slight deviation in the angle it moves during running. This angle is much smaller than the angle change during a tumbling timestep & it is sampled from a distribution that is suggested based on empirical data [1].

During a tumbling timestep, the angle of tumbling is decided such that the tumbling anlges is a Weibull distributed random variable as suggested in [1].

We have made sure that the movement simulated using the algorithm agrees with the observed behaviour of E. coli in Chemotactic motion.

Simulation Results

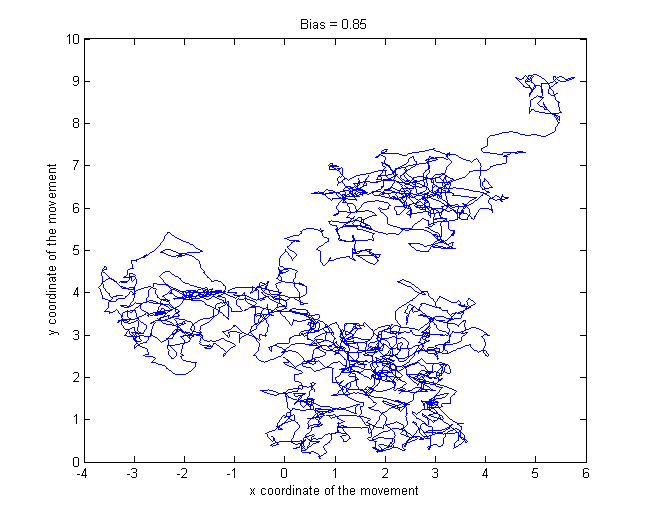

The most interesting part regarding the results of the Movement Model is the comparison of the behavior of the bacterium at different values of the input bias. Figure 2 shows simulations lasting 2500 seconds, for different bias values (final image to be uploaded)

References

[1] Chemotaxis in Escherichia coli analysed by three - dimensional Tracking. H.C. Berg, D.A.Brown: Nature 239, 500 - 504. 1972

[2] Levin, Morton-Firth (1998), "Origins of Individual Swimming Behavior in Bacteria", Biophysical Journal 74:175-181

"

"