Team:Davidson-MissouriW/MeasuringExpression

From 2010.igem.org

iGEM Davidson – MWSU 2010: Measuring Gene Expression

The system we originally designed to address the knapsack problem had several vital components. The TetA and RFP genes, along with their corresponding gene products, served as our reporters to see if and how a cell solved the knapsack problem. However, we recorded several observations regarding gene expression as we progressed. Characterizing and attempting to understand these foundational problems became one of the new focuses of this team.

Results from past Davidson and Missouri Western research hinted at the presence of a transcriptional terminator within the TetA gene. Any gene located downstream of the 3’ end of the TetA gene did not appear to be expressed. This gene codes for an effluent pump that physically removes the antibody tetracycline from the cell.

To test for the presence of this terminator, we created a construct with a fluorescent protein gene downstream of TetA. If TetA really does block transcription, we would expect to see no fluorescence despite induction of the promoter that precedes the construct (pLac+TetA+RFP). We also tested pLac+TetA+RFP to see if the gene products provided protection from tetracycline compared to a negative control..

The data suggest that the IPTG (0.5mM) inducer decreases cell density in all three cell types. In addition, the construct with TetA before RFP was only able to survive the presence of tetracycline (50ug/mL) when the inducer IPTG was present. These data imply that the inducer did increase gene expression even if overall cell density decreased. The construct fluoresced very little in comparison with the positive control (pLac+RBS+RFP) no matter what the conditions. The data support the hypothesis that there is a transcriptional terminator in the TetA gene.

We performed another battery of tests to compare the pLac+TetA+RFP construct to a construct with the pLac+RFP+TetA orientation. When compared to cells with RFP followed by TetA, the construct’s negligible fluorescence was even more apparent. Interestingly, the cells with the flipped orientation grew poorly in the presence of tetracycline but had a high fluorescence per cell. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the fluorescence is divided by such a low number of cells that small variations are magnified. Alternatively, the presence of tetracycline could be selecting for cells with high expression levels of both gene products. These few cells are producing high levels of TetA effluent pumps in order to survive. Correspondingly, they are producing a lot of RFP.

MG 1655 E. coli cells have a genotype that closely resembles naturally occurring E. coli. We did a direct comparison of RFP gene expression in MG 1655 cells vs. JM 109. The data we collected is shown in the graph above.

We also wanted to see if the MG 1655 cells were more prone to induction by IPTG. The data for this experiment is shown in the graph above.

While working with two pLac-RBS-RFP clones, we noticed that one of the clones seemed to have a much higher copy number.In order to document the copy number we performed cell density tests and extracted the DNA and determined relative DNA per cell for each clone. The results from this experiment can be viewed above. We do not have an explanation for this variation in copy number.

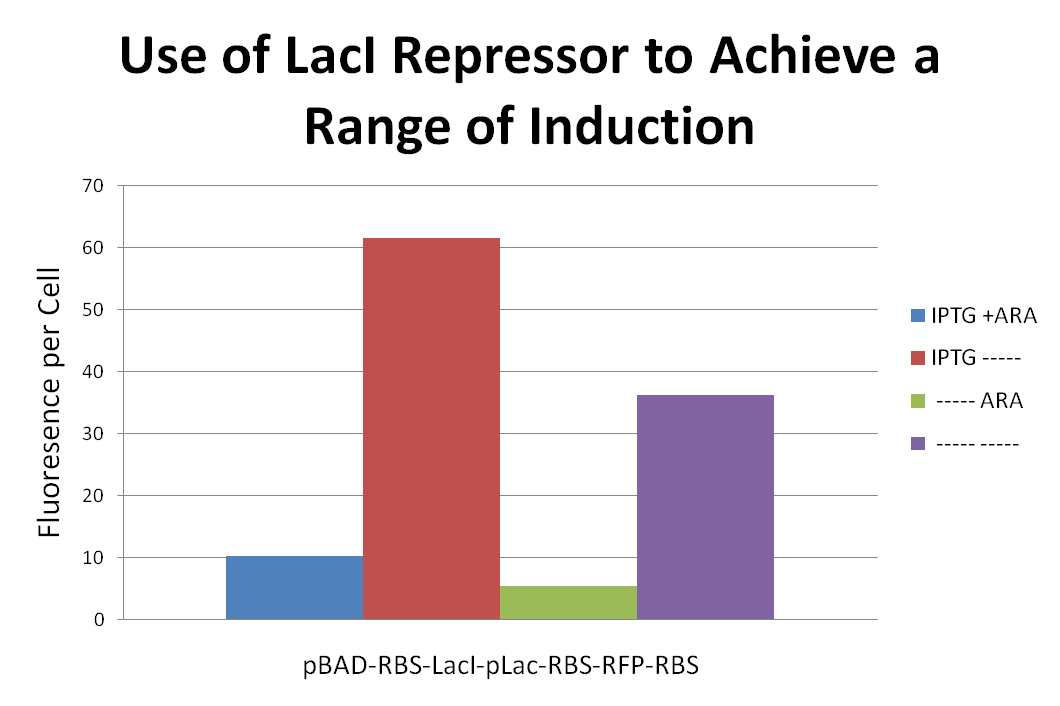

In order to achieve a range of induction of RFP expression we attached a LacI repressor to the front of a pLac-RBS-RFP-RBS construct. We then proceeded to induce with combinations of IPTG and Ara. Placing the LacI repressor onto to gene effected the level of RFP expression. Results can be seen above.

Over the summer, we synthesized a pLac-RBS-RFP gene and picked a pink colony and a red colony off our transformation plate. We sequenced the inserts and found that the DNA sequences were identical yet gave different phenotypes, one being a red colony and the other a pink. We were able to determine that red colonies had more red fluorescent protein being produced in comparison to the pink colonies, though we were puzzled at how this might be occurring consistently. We were able to determine that something inside the insert was allowing this to occur by doing experiments that involved switching of the inserts among the two vectors. This led us to suspect that an epigenetic mechanism was involved in this process. The mechanism we proposed was DNA methylation. DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to a nitrogenous base of the DNA. This modification of the DNA can be inherited through subsequent cell divisions and is known to regulate gene expression in a variety of organisms. Adenine or cytosine methylation (Dam or Dcm, respectively) is known to occur in many bacteria, including E. coli. Methylation could affect gene expression by making the DNA specific sequence harder to recognize by the polymerase; thus, decreasing gene expression. Methylation might also increase gene expression by having the opposite effect where the DNA binding site is more easily recognized by the polymerase, though this type is rare. We sought to determine if DNA methylation was actually playing a role in the gene expression of these E. coli cells. Our first experiment used three different restriction endonucleases that were sensitive to DNA methylation to see if any of the sites that are recognized by the enzyme are methylated. This experiment was not able to determine if any DNA in our gene was methylated. A future experiment that will help us in the determination of whether this gene is methylated is methylation-specific PCR (MSP).

In another effort to understand why the pLac-RBS-RFP construct was producing one set of red clones and one set of pink clones we designed an experiment to see whether the degree of red fluorescent protein was a function of the vector or the insert. In this experiment we performed a EcoRI/PstI digest on each clone and purified both the vector and insert for each. Then we put each of the inserts back into their original vectors as well as placing the inserts into the opposite vectors. The diagram illustrates the crosses. See pictures of the results of this experiment above. These results indicate that the color follows the insert.

As we were doing experiments with a pLac-RBS-RFP construct (part number I715039) we noticed some color variation between clones that were supposed to be identical. In an effort to trace the differences in fluorescence we spotted 2 ml of the two clones. These clones produced ring-like structures resembling a fried egg with a center, a middle, and an outer edge all of different colors. Sections from these colonies were picked, grown up overnight, and spotted again. Each of the new colonies showed similar results. We do not know the reason for the variation within clones, but are continuing to perform experiments to reach conclusions. View the pictures above in sequential order to see the color variations and how they traveled through generations.

"

"