Team:Wisconsin-Madison/encryption

From 2010.igem.org

Description

Abstract

Sequential logic switches are the basis for many common electronic devices such as digital clocks and calculators. Here we present a novel design for the imitation of sequential logic using basic genetic parts within E. Coli. By using a combination of DNA recombinase enzymes, promoter systems, and an innovative pattern of recombinase binding sites, we can reproduce sequential-logical functions on the compact molecular scale. By using single DNA molecules as a medium for such functions within bacterial vehicles, we can essentially mimic the functionality of a combination lock, and produce a "locked" gene which can be effectively "unlocked" only after a specific sequence of inputs detected by the bacterial promoter system. Since the DNA molecule is used as a logical medium, the "locked" and "unlocked" states are effectively heritable to subsequent bacterial cell lines, which would make such a system useful as the computational basis for many higher-order genetic devices from bacterial calculators to engineering of new metabolic pathways to bacterial drug delivery systems.

Background

Motivation

Increasing Complexity of Input

- If Synthetic Biology ever wants to get into the business of serious computation, single input promoters are probably not enough for most complex designs. By implementing a sequential circuit, we can produce a pseudo-promoter that responds, not to just one, two, or three separate inputs, but a promoter that responds to a number of inputs and the order they were detected. Once this system is working, we can store this pseudo-promoter into a black box and ignore most the complexities of the system. We can then make more intricate designs using this complex pseudo-promoter.

Solving Leaky Promoter Problem

- Promoters can sometimes be leaky. Using a sequential switch-like promoter system would, hopefully, solve the problem of leaky promoters. It would allow for more control over how the wanted promoter is expressed (see below for more information).

Storing Memory

- A sequential switch can be used to store memory. A recombinational flip can be thought of as a binary transition from "0" to "1" or "1" to "0". Recombination enzymes encoded by our "Key" plasmid will alter the orientation of certain segments on our "Lock" plasmid. Since the order of the inputs that the "Key" plasmid responds can be mapped to a unique orientation/combination of DNA on the "Lock," we can use our system to store memory of what inputs were detected and in what order. This memory can then be passed down to subsequent generations. By simply examining the orientation of the "Lock" DNA segments (sequencing, restriction mapping, gene transcription via a promoter inversion, etc.), we can determine what environment inputs the bacterial ancestors experienced in the past. Storing memory in an organic system is an amazing concept! We can then begin to preform serious computations and store this information by mapping it into a storing plasmid (aka the "Lock" plasmid) like computer memory!

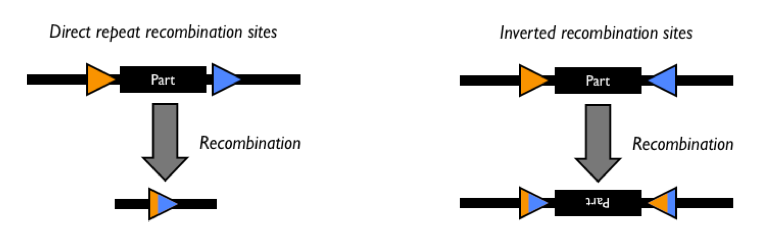

Recombination

Site-specific DNA recombination can occur in a number of ways resulting in deletion, inversion, or insertion of DNA. The recombination event requires a recombinase protein and a pair of enzyme-specific DNA recombination sites. Sometimes a host-factor or a enhancer sequence is required in addition to the recombinase and the recognition sites for the recombination event to occur.

The Parts Registry also has a page devoted to DNA Recombination.

Two-plasmid System

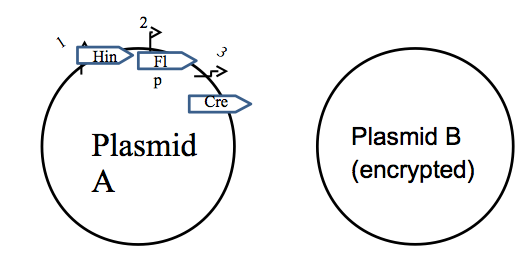

Our system utilizes two plasmids. One plasmid acts as the recombinase producer (called the "key"). The other acts as the medium for recombination (called the "lock").

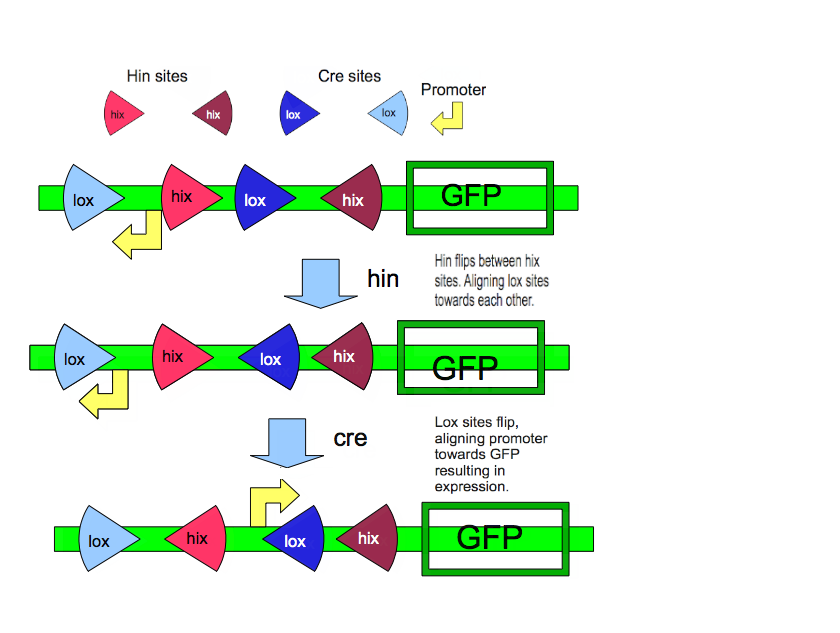

On the "Key" plasmid, exists a set of genes encoding proteins for translation. In front of each of those genes is a unique promoter that corresponds to some positive or negative input (ex. pLac promoter). On the "Lock" plasmid, a gene of interest is potentially translated by a promoter. However, this promoter 'inactive' with respect to our gene of interest, either by being inverted with respect to the gene, or translation is effectively terminated before the start codon of the gene. Depending on a combination of recombination sites, the gene's promoter is encoded; to unlock this gene, what is required is the correct sequence of recombination enzymes (aka correct set of inputs with respect to the "Key" plasmid. A two component encryption system is depicted below. What is displayed is a simple "Lock" design for such a system.

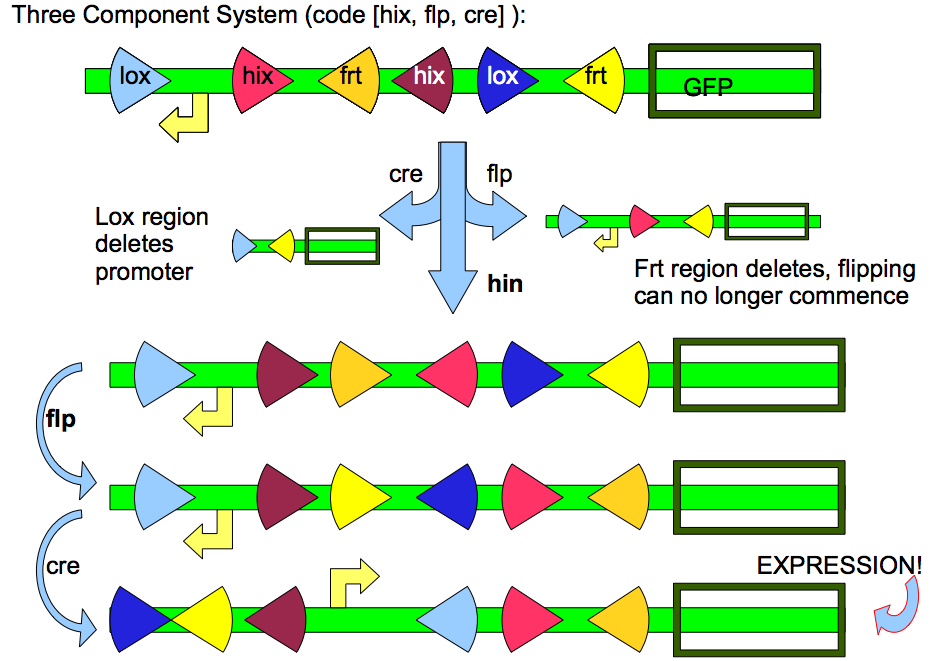

The complexity of the Encryption System can increase and is only limited by the number of unique promoters and unique recombination enzymes:

Theoretically, the complexity of the system can increase to N-"Lock" encryption systems; there are many different designs for some N-"Lock" Encryption system. Such designs can be calculated using a computer and a Constraint Satisfaction algorithm. For example, the three-component encryption above is a result of such an algorithm.

Parts

The Key Plasmid

The Key Plasmid produces recombinase enzymes based upon specific chemical inputs. These enzymes recognize the recombination sites on the "locked" plasmid and alter the DNA.

The Lock Plasmid

The Lock Plasmid provides the medium for the recombinases produced by the "key" while maintaining a "locked" promoter region thereby controlling expression of genes attached to the "lock." The lock only becomes unlocked after a specific pattern of recombination events, and the Lock Plasmid is passed on to future generations of bacteria.

Testing

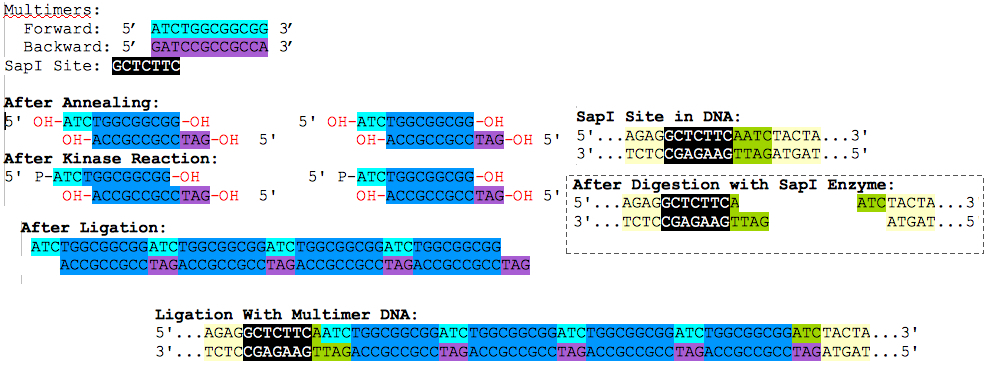

We planned on producing a two-component encryption system, using RFP and GFP as indicators of the promoter position. We also input a restriction site, SapI, to vary the length between the sites by inserting a length of DNA, using a experimental primer polymerization reaction. The idea is that the recombination enzymes act over an optimal distance between the corresponding recombination sites. By adjusting and testing for a variety of lengths, we can discover this optimal length and further characterize these recombination enzymes for future design use. The basic concept for the polymerization reaction used is depicted below:

After preforming the multimerizing reaction, the subsequent reaction was run on a gel and length segments of our choosing were cut out from the agarose gel. Optionally, the same primers can be ligated to the appropriate ends to lengthen the sticky ends of the vector and multimer insert.

With the polymerization reaction, we managed to insert a 250bp fragment into the SapI site of our "Lock" plasmid. However, this reaction was determined to be very costly, in terms of time and reagents, and it would be much more efficient to simply cut out an appropriate length of DNA from some other plasmid, and insert it into our "Lock" plasmid.

Results

Unfortunately, we never got to testing our systems. We managed to clone a two component encryption system (as depicted above). Rigorous testing of our system never occurred due to time constraints of the competition. Our enzyme delivery took precedence as the competition drew near and our financial resources became more and more strained.

"

"